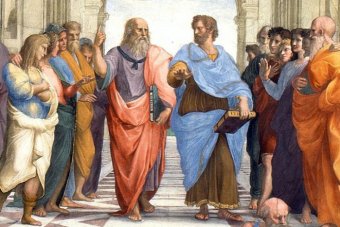

Re-reading Plato and Aristotle has made me to realise that by neglecting ancient philosophies and being preoccupied with neo-liberal thinking stemming from utilitarian philosophies have led us to a major crisis in our political and governmental affairs. The vital institutions of our democracy are now widely held in contempt by the public because we have neglected the foundations that underlay their former respect. Having forgotten the teaching of Plato, Aristotle and many other thinkers and subscribed to only judging actions by their consequences, the result is a major crisis of confidence in our political and government systems. What have we lost?

- Citizenship. As a result of the misnamed ‘Citizen’s Charter’ launched by John Major in 1992, we now have an attenuated view of citizenship as consumerism; as being equivalent merely to the relatively passive choices we make when going out shopping. This has even led some to argue that this economic democracy can replace local political activity. Aristotle stated that citizenship demands that we accept the right and the duty to participate in the government of our communities. This means not only voting and sitting on juries but participating in politics as MPs, councillors, party members and in lobby groups. The response to disillusion with politicians is to become politically active oneself and hence become a citizen properly defined.

- The public interest is not merely the sum of individual interests, as the Benthamites argued; nor should our support for the public interest be merely self-centred. The continued stability of our state and the maintenance of good governance are essential if our private businesses and other activities are to flourish. As Pericles reminded the citizens of Athens during the Peloponnesian War: “since a state can support individuals in their suffering but no person can bear the load that rests on the state, is it not right for us all to rally to her defence?”

- The public service ethos is now missing because of our undue preoccupation with business values and methods as a means to improving public services. We need to inculcate public servants at all levels with the Nolan Committee’s seven Principles of Public Service: selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership. Above all, we need to renew the requirement imposed on our governors, handed down from Plato onwards, that they must govern dispassionately, without having regard for their individual interests. Public choice theorists have denied the possibility of doing so; but their thinking is misconceived. Public administration is, in Rousseau’s terms, an “unnatural” activity, which requires that public servants – politicians and officials alike – must govern dispassionately and disregard their personal interests. Strict rules concerning declarations of interest by MPs, Peers and councillors would help restore this duty. But fundamentally, this requires the restoration of the ethical value of dispassionate government.

- However, the ability of public managers to do this has been badly weakened by the abandonment over the last thirty years of public service education and training, largely because it has been absorbed into business school curricula, which mainly teach business ethics and methods and whose members are therefore unfamiliar with the ethical requirements that should be imposed on public servants. We need to reinstate specialised education for public service professionals – ethical, legal and institutional education at both the initial and in-service levels – in order to inculcated public service ethics and to impart knowledge of the governmental systems is which politicians and officials work. This includes the several forms of accountability to which they are and must be subject to.

- The good life. Plato, Aristotle and many others, including religious authorities, urge us to pursue higher goals of virtue and excellence in our public and private lives. Yet we have lost sight of the duty to promote excellence as well as economy, efficiency and effectiveness. The public choice theorists have led us to believe that we cannot be other than selfish rational ‘maximisers’. But Plato, Aristotle and many others (including Jesus Christ) teach us that we should seek higher moral goals than just making a living or a profit. Thus, a journalist should aim to give readers a true and intelligent picture of the world, not just seek to increase the paper’s circulation. A lawyer should ensure that justice is done, not just enlarge his or her practice. Businessmen should be nurses to their communities, not just seek personal enrichment. Again, legal and administrative reform can help: strict restrictions on the current unedifying practice of retiring Ministers and senior civil servants taking seats on the boards of the companies they previously dealt with as public servants must be restored. Expenses systems at all levels must be subject to strict rules and be properly audited. Still, more is required. Public servants must strive to achieve the higher goals of the state to promote the search for virtue and excellence. All out activities should be devoted to improving not only our own lives but also those of the people around us, and also the wider societies in which we are part.

No Comment