Homeland Calling: The Chinese Diaspora and Beijing’s Worrying Embrace of Ethnic Nationalism

Recent years have seen a global resurgence of ethnic nationalism. Yet, political identities based on ethnicity are nothing new. In fact, ethno-nationalist desires reshaped Europe’s borders in the early 20th century with devastating consequences. Despite more than seven decades of relative peace, largely kept in place by the multilateral organizations and deepening global integration, nationalism appears to be returning to the forefront of politics once more. In Europe, politicians and political parties are tapping on anti-immigrant nationalist sentiment. For instance, Italy’s Matteo Salvini has openly advocated solutions which involve marginalizing ethnically-defined “others”. Rogers Brubaker, professor of sociology at UCLA, has coined the term “civilizationism” to describe the rhetoric used by multiple European political parties which claims that the ethno-cultural homogeneity …

Nurture and nature: education, blood and nationality

On the 28th of October 1940 the Greek government rejected Benito Mussolini’s ultimatum demanding that Axis forces were given free entrance from neighbouring Albania and allowed to occupy strategic locations around the country. After the war, this momentous event in the history of modern Greece – popularly known as the No Day – became a national holiday, celebrated annually with impressive military and student parades.

Fourteen years ago, one such parade had to take place in a town near Thessaloniki. As a tradition, the best student in the local high school was expected to bear the Greek flag. The best student, though, was not Greek. He was an Albanian immigrant.

Pupils, parents and citizens throughout Greece rose in anger: despite his achievement, how could a non-Greek, an alien, a non-citizen at that, be allowed to carry the national colours? The government, the main political parties and the teachers’ union stood behind the excellent Albanian student but the boy responded to the growing commotion by choosing to step aside, allowing a Greek pupil to carry the flag.

Three years later, the same Albanian – having now distinguished himself as the best graduating student of his school – was again elected to bear the colours in the Greek national holiday parade. The public outcry, in this instance, grew even wider and sharper than earlier. The young man, for a second time, decided not to accept the honour but pass it on to a native schoolmate instead.

The volcanic public discourse surrounding these events had nationality, citizenship and ethnic origin at its centre. Blood, heredity, and even DNA, became salient elements of the debate – pitted against the qualities and achievements of the person, his or her social integration, active participation in and contribution to the Greek scheme of life. ‘What makes one truly Greek: one’s Hellenic outlook, behaviour and genuine belief in Greekness, one’s abilities and success in Greek society and/or one’s historical roots and genetic ancestry?’ was a question resounding loudly across the country and the region. Is it nature or nurture, a cocktail of the two, or perhaps something greater than that, which makes us genuine sons and daughters of a country, a nation or a people?

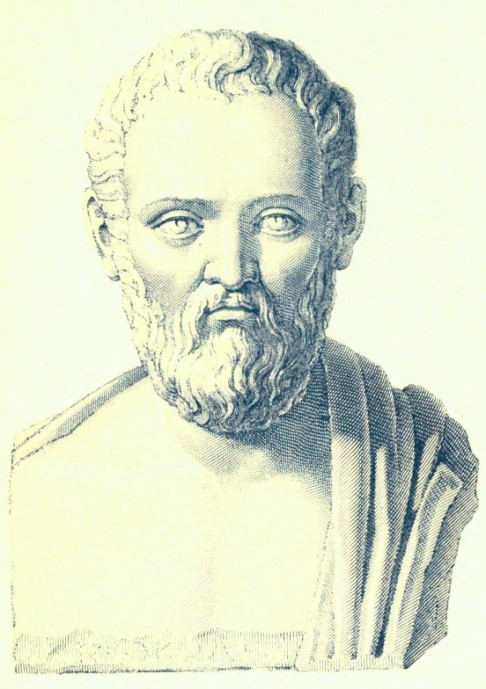

The perennial echo of this problem was picked up by the then president of the Greek Republic who, in defence of the Albanian student, quoted a line from a famous work by the great Athenian rhetorician Isocrates. “[Athens]”, the ancient man of letters writes in his Panegyricus, “has brought it about that the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and that the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood”.

Nasty piece of work: The Sun’s nationalism is doing England great harm

Other than war, few things fire nationalist sentiments in a society quite like sport. On June 27 2010, as the English football team were being thrashed by Germany in the World Cup in South Africa, England’s fans chanted: “Two world wars and one world cup … two world wars and one world cup!”

As pacified contests, sports generate all the emotions of national attachment in a manner that is generally benign and fun. Yet major sporting events also offer opportunities for those seeking to mobilise national identity in a more aggressive way – as The Sun newspaper recently reminded us with its free “Historic Edition”, dispatched to 22m homes in Britain last month.

Make no mistakes about the official prompt of this paper being the start of the World Cup – this is quite visibly a deliberate political publication, the latest effort by the UK’s highest circulation newspaper to shove popular understandings of national identity in its preferred direction. The effort is hardly covert, with the front cover emblazoned with the words “THIS IS OUR ENGLAND” superimposed over the faces of 117 individuals the Sun deems personal embodiments of “the essence of England today”.

The paper’s contents offered an unusually sustained illustration of English nationalism as interpreted by Britain’s tabloids. It’s not a pretty picture. After a superficially worthy iteration of that now trite sentiment of British politicians, public intellectuals and commentators that national pride needs to be “reclaimed” from the “small-minded” and the “racist”, the following 21 pages provided a tour de force in national chest-thumping that could barely do more to put its small-mindedness and contempt for the rest of the world front and centre.

The Myth of the ‘Mighty Minnows’: Small nations aren’t the economic successes they think they are (or may become)

Nationalist movements often argue that small countries are more economically successful than big ones. The Scottish Nationalist Party claims that independence would allow Scotland to advance from ‘its subordinate position within the UK, and generate a new prosperity for Scotland’. And former Plaid Cymru MP, Adam Price, who is currently taking a career break at Harvard University, goes further, wrapping the ‘small equals rich’ argument in a cloak of pseudo-academic jargon. Price’s article, published in an on-line student journal, is entitled ‘Small is Cute, Sexy and Successful’. He argues that smaller countries grow faster because they are more open to trade, more socially cohesive and more adaptable. Rather optimistically, Price even argues that differences in population size alone account for ‘mighty minnows’ outperforming the big five (UK, Italy, …