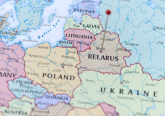

Bloody clashes in front of the Ukrainian Parliament have reminded us about the EU’s tormented neighbour. Ultra-nationalists were not successful in the last parliamentary elections, but the tragic situation in Donbas has allowed them thrive. At stake this time were planned changes to the Ukrainian Constitution that envisaged a territorial decentralization as stipulated by the Minsk Agreement. For Ukrainian radicals these changes “imposed” from outside amount to a partition of their country. Is Ukraine unravelling? I do not think so, but much depends on Europe.

European leaders said many times that the future of Europe and Ukraine are entangled. The last thing they want is to have a huge failed state on their eastern border. This is why President Poroshenko is being offered red carpets, lavish dinners and numerous photo opportunities in European capitals. Sadly, very little results from his visits, photos and dinners. So far the EU has failed to give Ukraine a significant economic aid, lift visa restrictions or invest seriously in Ukrainian civil society institutions. Never mind talking about providing ammunition or arms to defend the troubled country.

If Ukraine is so important for the EU, then why does the EU do so little to assist it? My explanation points to a paralysis of the mind, or if you wish, to a lack of trust and imagination. EU leaders seem not to believe that Ukraine can achieve what Poland has achieved over the past two decades. Why invest time, money and careers in a lost cause? This fatalistic thinking explains or even “justifies” the EU restraint to a large extent.

There are different types of fatalism at work regarding Ukraine and all of them contain some truth. The problem is that fatalistic thinking perceives Ukraine in black-and-white colours; Ukrainian problems are emphasized while improvements and opportunities are ignored. However, if you look at successful transitions to peace, democracy and a free market you can hardly ever see linear progress. Successes go hand in hand with set-backs; joy is accompanied by frustration if not despair. The end result is also far from any text-book model. The same should be expected in Ukraine and there is no reason to entertain fatalism each time something goes wrong as was clearly the case on 31 August.

The first type of fatalism regards geo-politics. At its centre are the imperial ambitions of Russia. Russia will never let Ukraine leave its sphere of influence, the argument goes. To start with, Russia is much weaker than the Soviet Union was, and the all-powerful soviet empire is now in tatters. Even if Russia has imperial ambitions, it is far from certain that she can realize them. There is little evidence suggesting that Putin believes that all of Ukraine can be pacified by his soldiers. One thing is to invade a country, quite another to rule it. There is more evidence suggesting that Putin intends to frustrate Ukraine’s quest for democracy and economic development, but in this field the EU could make a tangible difference. Here enters the second type of fatalism, however.

Hardly anybody believes that Ukraine will manage to complete economic and democratic reforms while engaged in a hybrid war with Russia. However, cases such as Israel or Georgia question this kind of fatalism. Hardly anybody believes that democracy and a truly free market can be constructed in a poor and corrupted country such as Ukraine. However, cases such as India or Romania question this kind of fatalism. National conflict does not need to be an obstacle to democracy or a free market. How did Canada or Belgium become affluent and democratic? In other words, history knows many cases of successful transition to democracy and free market despite mounting economic, social or cultural problems.

This leads to the third type of fatalism: failure is Ukraine’s historical fate. Ukraine has not succeeded in becoming an independent, prosperous and democratic state in 1918, 1991 and 2004. What makes us think that this time will be different? This type of historical fatalism is also easy to question. Poland failed to enter the club of independent, prosperous and democratic states many times in its history and now it represents a model country within the entire EU. How many times has Germany found herself on a wrong historical path? Or think about Croatia, which only a few years ago was in the midst of a bloody conflict. Sometimes countries draw correct lessons from their historical failures. At other times they skilfully utilize geo-political or economic openings. In any case, it is not true that certain states or nations are condemned to war, poverty and tyranny.

That said, there is one type of fatalism that is hard to contest: Ukraine would not be able to resist Russia, construct democracy and develop a healthy market without external help. The EU invested in small Greece ten times more than in huge Ukraine. The EU engaged an enormous crowd of bureaucrats to run Greece, while the EU “support group” for Ukraine has only thirty full time officials. The government in Kiev does not need lessons from Brussels on how to cope with Russia; in this area Ukrainians have more experience. But the government in Kiev needs meaningful help from Brussels to restructure its debts, to prevent oligarchs from washing money in Western banks, to protect poor citizens from the harsh implications of reforms, and to enhance the rule of law and institutions of civil society. A few legal advisers and Erasmus fellowships are not sufficient.

On EuroMaidan numerous Ukrainians lost their life struggling for Europe. Ignoring their sacrifice would have a powerful symbolic meaning not only for Ukraine, but also for the EU. Those fighting on EuroMaidan probably had too much imagination and hope, but the EU could benefit from a fraction of this imagination and hope.

This article was originally published in Polish at polityka.pl, and in English at Open Democracy.

No Comment