The Western Balkans have been a core theme in the political programs of subsequent presidencies of the Council of the European Union in the last years. Both the Austrian and Bulgarian presidencies highlighted the importance of the region and placed the topic on the agenda. A similar emphasis is supposedly followed by the Romanian Presidency that started on January, 1st, 2019.

Yet, one key piece is missing from the Romanian agenda and its approach towards the presumable future enlargement in the Western Balkans: Kosovo. Neither the programme of the Presidency, nor national debates talk about Kosovo and its relationship with the European Union. Ignoring Kosovo does not mean that the issue is still not there. Romania remains one of the five EU member states not recognizing Kosovo and continues to have extremely limited interactions with the country.

The explanation for this lack of engagement with the Kosovo issue is an utterly unchallenged stance to not formally recognize Kosovo. The non-recognition of Kosovo is endorsed by all established political parties, with the exception of the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania. However, the emergence of new political parties in recent years creates an opportunity to address the ties between Romania and the Western Balkans in general and Kosovo, in particular.

Debates about Recognizing Kosovo

Romanian political parties have long expressed a clear refusal to recognize Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence. On 18 February 2008, with a large majority – 357 in favour and only 27 against – the Romanian Parliament adopted a declaration against this recognition. The reasoning behind this position embraced a legalist approach, as Romania accused Kosovo of breaching international law.

Alternative narratives have been promoted and grown stronger, portraying Kosovo as a presumably dangerous precedent. A parallel was drawn between Kosovo’s independence and the fear of secession in Székely Land – a Romanian region inhabited mainly by ethnic Hungarians, the status of the breakaway region of Transnistria, and, after 2014, the illegal annexation of Crimea. What’s more, the almost mythologized relation between Romania and Serbia, based on links with former Yugoslavia during communist times, is often referred to.

Unchallenged from within and supported by a broad consensus among the mainstream parties (including the Social Democrats and National Liberals – the two main political groups), political debates of the topic of Kosovo’s independence and Romanian-Kosovar relations have been non-existent in the last decade.

Positions on Kosovo among Romania’s Parties

In 2016, Romanian Center for European Policies carried out one of the few quantitative analyses of the Kosovo question in Romania. Surveying members of the Romanian Parliament, 202 MPs responded to the questionnaire (51 members of the Senate and 151 members of the Chamber of Deputies – from 506 contacted MPs). Several results of the survey stand out.

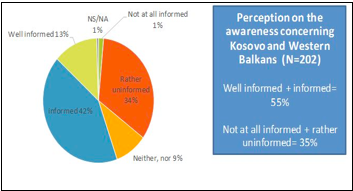

First, the study showed large discrepancies between Romania’s public positions and knowledge of the issue. Although 85% of the respondents believe that Romania’s role in EU’s enlargement policy in the Balkans is important, only 55% believe they are informed or well-informed about the Western Balkans and Kosovo in particular.

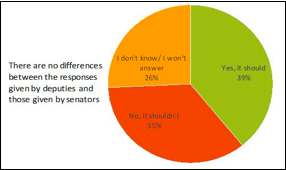

Second, data from the study shows that 39% of the MPs believed that Romania should recognize Kosovo, 35% were against recognition, and 26% did not respond to this question. These pro-recognition figures are not negligible and, at a first glance, seem substantially higher than would be expected public debates and party positions against recognition.

There are two main explanations for the lack of knowledge and support for recognition. Firstly, Romanian political parties, especially mainstream ones, are hierarchically organized and disciplined, with critical decisions being taken by core members of the party that are rarely challenged from within. In addition, despite the fact that the political parties stick to the non-recognition policy, there is also distress among rank-and-file members for being out of sync with most of the European families and Romania’s most important partners.

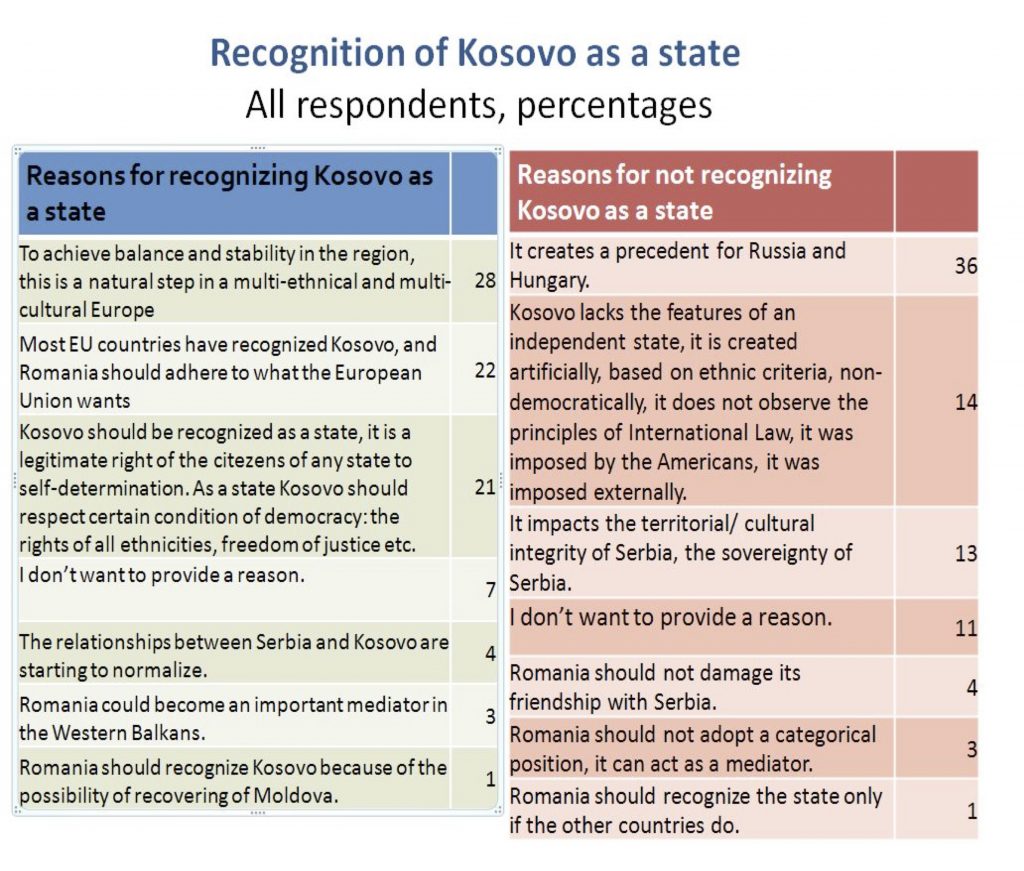

A closer look at the stated reasons for supporting or opposing the recognition of Kosovo provides more insights. The reasoning behind MPs positioning against was in line with the narratives that dominate the public debates: 36% of the MPs indicated that “it creates a precedent for Russia and Hungary”, while 13% argued that “it impacts the territorial integrity of Serbia”, while the pro-recognition side argued that “Romania should follow EU partners and the US and recognize Kosovo.”

The survey also found that the issue is not very salient for most MPs. Nowadays, the topic of Kosovo is even more marginal on the public agenda, absent in the political programs of the parties and also in the official programme of Romania during its Presidency.

The region is also receiving critical low attention from the Romanian decision makers in contradiction with the official position of Brussels that put back the Western Balkans under spotlight in the last years in an attempt to counter Russian and Turkish influence. On Kosovo, in the absence of either consensus or attention of established political actors, which could probably happen only following a major external event, the Romanian policy of non-recognition remains the default political position.

New political parties and the Kosovo Question

Another external catalyst for change might be the emergence of new political actors on the scene. Indeed, the Romanian political environment has undergone significant changes in recent years, as new political parties have emerged, especially Union Save Romania (USR) and theParty of Liberty, Unity and Solidarity(PLUS), organized around former Romanian Prime Minister, Dacian Ciolos. Recently, the two parties managed to receive almost a quarter of Romanians’ votes during the EU elections, confirming their growing influence at national level.

Parties such as USR and PLUS could jump-start more substantive debates on Kosovo, by not being tied down by some of the alternative narratives and fake news that have characterized the debate. Yet, to this date, neither of these parties has developed a clear agenda concerning the Western Balkans or Kosovo, with the sole exception of having conveyed a general message of support for EU enlargement in the Balkans.

During the past three years, when the first of these parties emerged and took part in the elections, Kosovo has been a marginal topic, thus there was little incentive for taking a strong stance. Nevertheless, these new political parties or certain groups within established parties could take incremental steps towards enhancing relations and increasing engagement with the region in general and Kosovo in specific that does not require going as far as recognition.

Conclusions

At the moment, official political channels between Kosovo and Romania are rather non-existent, similarly people-to-people exchanges (at academic or cultural level) remain critically low. As long as the entire political spectrum in Romania – regardless whether it is the established or newcomer parties – shares a common view regarding the policy of non-recognition towards Kosovo, the prospects for fundamental change seem remote. After having been a hegemonic and unchallenged position for almost a decade, any sudden shifts from within are highly unlikely.

Romania’s official position is widely supported by its political parties, and, in the absence of an agreement between Belgrade and Pristina, it is very improbable that Kosovo’s recognition will be even debated internally. However, this is not an immutable status quo. As the Romania’s political landscape is gradually changing, so might the answers to the Kosovo question.

An extended version of this article will be published as part of the project Building knowledge about Kosovo (2.0), supported by Kosovo Foundation for Open Society.