With the diversion of Israel’s military resources towards West Bank, Israeli annexation of occupied Palestinian territory appears imminent, pending approval from and coordination with the American administration. Struggling to rally right-wing voters amidst the fight for his political survival in the elections of April, September 2019 and March 2020, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had stated that he would “apply Israeli sovereignty” over the West Bank, if re-elected. Bolstered by the reversal of decades of American policy on the issue and the subsequent release of Trump’s much criticized, one-sided ‘Middle East Peace Plan’ in January 2020, Netanyahu has aggressively pursued the annexation agenda with the emergency government formed with Benny Gantz in March 2020. Considering the expected blockage of the Security Council (SC) on the issue, this article argues whether that the UN General Assembly’s (GA) Resolution 377 (V), known as ‘Uniting for Peace’ (UfP), should be invoked to allow the international community to act on the issue.

The framers of the UN Charter had granted veto power to the five permanent members (P5) of the SC, understanding their ability to maintain world peace as the primary responsibility of the SC. However, use of the veto power to further national and political interests rather than to maintain international peace became central in the early years of the Council’s work, highlighted by the Soviet Union’s vetoes against resolutions to intervene in Korea. In response, the western powers in the Council led by the US moved the GA to adopt a resolution that enabled the Assembly to meet if the SC fails to act on a critical matter of international peace and security. This resolution came to be known as “Uniting for Peace” or the “Acheson Plan.” It aimed to enable the GA to assume the powers of the SC, albeit without the enforcing powers of the SC (Carswell: 459). These powers, restricted to recommendations, are not binding upon member states, but do possess force as customary international law. The resolution has been invoked twelve times, with Israel being the cause of invocation once each by the SC and GA.

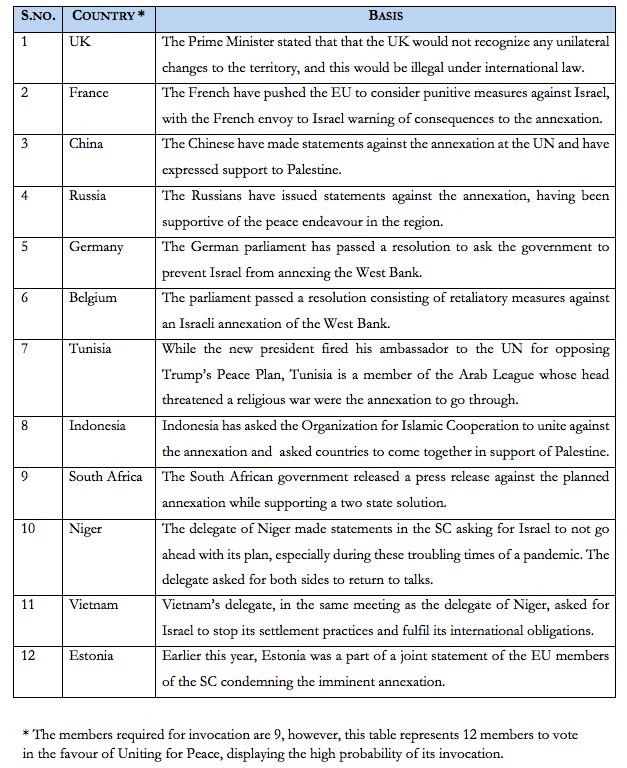

The current situation meets the requirements for invoking the UfP resolution, which requires both a veto vote by one of the P5 and either a threat to peace, breach of peace or an act of aggression. The US has vowed to veto any resolution tabled in the SC against the move, fulfilling the first requirement for a UfP resolution. Is there, though, a threat to peace, breach of peace or an act of aggression? This is ordinarily determined by the SC under Article 39 of the UN Charter. The ability to determine the fulfilment of any of these three situations and thereafter the invocation of the Uniting for Peace resolution resides with the GA as well. Per Resolution 3314 of the GA, the forceful annexation of the territory of another state is recognized as an act of aggression which represents a clear threat to peace. Therefore, notwithstanding the illegality of the move itself, the annexation fulfils the second criterion for the invocation of this resolution. It can be invoked by referral of any nine members of the SC or a majority of the members of the GA itself. It seems likely that the resolution would pass if proposed, as twelve members of the SC have endorsed opposition to the Israeli policy (Table 1).

However, before the UfP is invoked, three important counter-arguments need to be addressed.

One, why should the resolution be invoked now, and particularly on this issue? The SC has received criticism for its staggered response to various international crises. However, it has managed to act, even in some highly contentious conflict situations, including on Libya and Syria– issues over which the P5 were divided, but did arrive at a consensus. Even the annexation of Crimea was acted upon by the SC, despite Russia being directly involved, by way of the implementation of the Minsk agreement. However, this has not been the case with matters related to Israel, which separates the issue of the imminent annexation from various other situations around the world. Israel has remained untouched by the SC in spite of severe international opposition towards its transgressions. Its historical impunity in the SC, for the gravest violations of international law, is exemplified by America’s Negroponte Doctrine. The demonstration of this impunity reached a new high when Netanyahu announced his plan, knowing that the only body capable of restricting his plans is the SC, where he sits well protected by the US and its veto. This ‘might is right’ approach needs to be addressed seriously. Moreover, if the threat of annexation is allowed to persist without any international response, it could likely mark the return of annexation as an acceptable international strategy. Thus, to bring attention to Israel’s steady impunity for its persistent transgressions and to prevent further reversion to unilateral aggression, the resolution must be invoked at this time and on this issue.

Two, this would raise the ‘usual vitriol’ from the Israeli right and American conservatives as to ‘Israeli Exceptionalism,’ the belief that Israel receives disproportionate attention in the UN. This ‘anti-Israel bias’ argument no longer appears sustainable, given its foreign policy losses and Israel’s deteriorating legitimacy. As Roger Cohen argued, Israel needs to approach the issue realistically since it is one of balance of power, not existential threats or race wars. It must adopt a “more prosaic, realistic self-image.” Even so, preventing annexation to preserve a world order based on universality and reciprocity is in the direct national interests of the international community. Thus, Israeli exceptionalist rhetoric cannot be allowed to deter a proportionate response.

Three, it is settled practice that the GA can act on matters pertaining to the maintenance of international peace and security even without reference to the Uniting for Peace Resolution (Johnson: 112). Why then should the resolution be invoked to act on this issue? The idea of annexation as a unilateral act of aggression- long taboo in international law and politics- has no place in the modern global order. Thus, a violation of international law as grave, alarming, and dangerous as annexation merits extraordinary treatment. Such a situation ought to be highlighted in the GA not merely for the non-binding collective measures, but also as a moral imperative reaffirming the raison d’être of the secondary collective security system envisaged by the drafters of the resolution. The invocation of this resolution would be testament to the overwhelming will of the international community not to be held hostage by a single veto. Moreover, it would serve as a reminder that the mere paralysis of the SC does not relieve the GA—the most inclusive conference of States—of its secondary responsibility to protect the foremost global value- international peace (Carswell: 464).

Annexation, if effectuated, will produce economic, political and security fallouts– including an existential threat to neighbouring Jordan, refugee and identity crises in Egypt, a looming massive-scale humanitarian emergency, sprouting of radicalism on all sides and obliteration of any prospects of sustained peace in the region. The international community must do more. Thus, the plans for Israeli annexation offer the correct context to constructively animate the moribund UfP resolution and for the GA to act collectively on this major threat to international peace.