U.S. presidents have powerful political incentives to think twice before escalating a conflict in the lead-up to an election. Recent events in the Gulf suggest that President Trump is no exception when it comes to avoiding the commitment of “boots on the ground” in an election year.

As both commander-in-chief and holder of the highest elected office, presidents must carefully weigh the political consequences of any decision regarding military strategy. Since voters tend to bear the brunt of the human and financial costs of war, decisions to send additional U.S. forces into combat are often fraught with risk of consequent reprisal at the ballot box.

In my recent article in International Security, I explore how these electoral pressures affected decision-making during the Iraq War. Drawing on recently declassified documents and interviews with key policymakers and high-ranking generals, the escalation of the war in 2007 demonstrates that the influence of electoral constraints extends even to congressional election campaigns. Even though the president is not on the ballot in midterm races, changes in the congressional balance of power have significant potential to derail a president’s legislative ambitions at home or forestall sustained commitments overseas through the body’s power of the purse. Since voters often cast ballots in congressional elections with a president’s record in mind, it pays to be particularly mindful of public opinion in the lead-up to Election Day.

Policy Change in the Iraq War

For much of the war, U.S. military strategy emphasized training local forces so that they could shoulder an increasing proportion of the security provision in Iraq, while U.S. forces gradually withdrew. As President George W. Bush noted in 2005, this transition strategy could be summarised as follows: “As the Iraqis stand up, we will stand down.”

In January 2007, however, Bush announced the most significant strategic shift of the Iraq War. Under a new plan, more than 20,000 troops would be sent to the Middle East in an attempt to boost security amid spiralling sectarian violence. The strategy, which would come to be known as the “surge”, shifted the focus to a revised counterinsurgency approach with U.S. troops in the lead.

The decision was a long time coming. Doubts about the existing strategy had been swirling around the administration for months. According to a senior official, by the spring of 2005, “the whole circle around the secretary of state were seethingwith frustration about the Iraq situation. We could feel it killing the administration.” Before long, the president, too, would privately count himself among the doubters.

Why did Bush wait until after the 2006 midterms to change his approach?

I argue that the “surge” illustrates a key mechanism of electoral constraint: when facing a politically controversial choice in the run-up to an election, politicians’ first instinct is to delay making any decision until after polling day. I trace this delay effect through four stages:

First, I show that the administration perceived a clear need to change strategy. “This is a daily conversation in the White House,” recalled Meghan O’Sullivan, Deputy National Security Adviser for Iraq and Afghanistan. “It was very clear that he was concerned about the situation, worried that it was going in the wrong direction.” Faced with mounting reports of deteriorating conditions, Bush frankly admitted that the strategy was not working. “We need to take another look at the whole strategy,” he told an aide at the time.

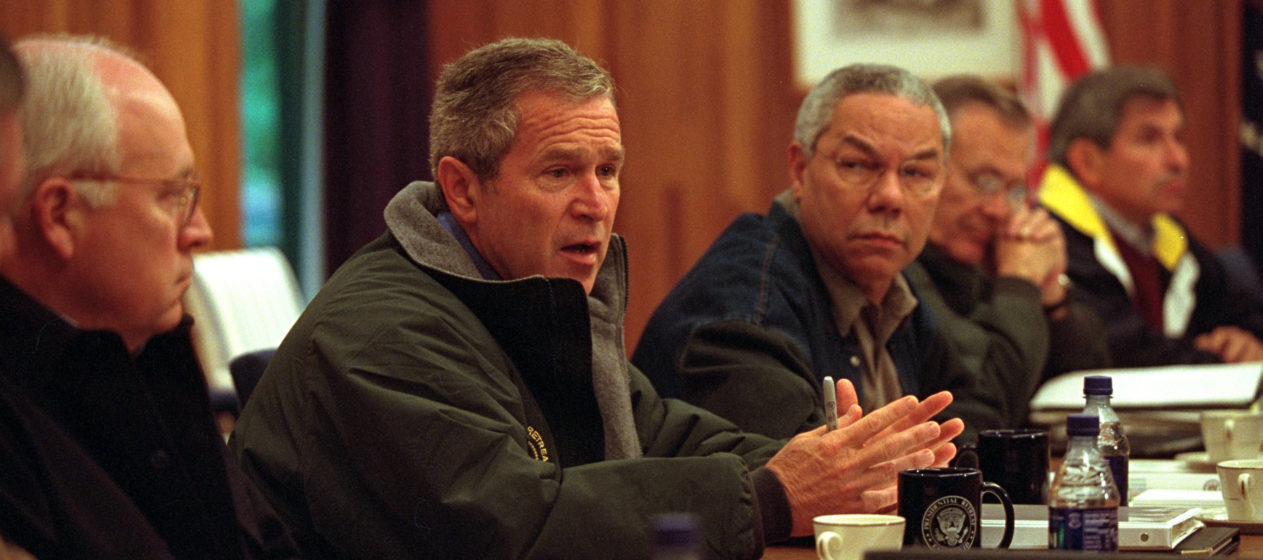

Second, the record reveals a series of missed opportunities to initiate a full interagency review. The most notable of these was a “war council” summit held at Camp David in June 2006, at which advisers expected to have a warts-and-all conversation about strategy. Instead, as a senior State Department official recalled, it “turned out to be a bust.” The president left secretly halfway through, using the meeting as cover for a trip to meet with the Iraqi Prime Minister. As a result, frustration with the existing course of action was left to stagnate in bureaucratic silos as a series of independent efforts to spark a change in approach were left to fizzle out.

Third, credible evidence exists pointing to electoral reasons for this pattern of delay. As Bush himself put it in his memoirs, “I decided a change in strategy was needed… [But] with the 2006 midterm elections approaching, the rhetoric on Iraq was hot… I decided to wait until after the elections to announce any policy or personnel changes.” Admitting that things were so bad that the administration was considering a change was politically damaging enough. Yet, the president also understood that the kind of escalatory move he appeared to favour would prove deeply unpopular with voters at a time when Republican majorities in Congress were at risk. With polls revealing vanishingly small support for any increase in troops, the administration instead became increasingly concerned with minimising the visible costs of war as the midterms loomed. Such heightened casualty-sensitivity in the run-up to polling day is exactly what theories of electoral constraint predict.

Finally, I demonstrate that the midterm elections of November 2006 acted as an important turning point, with obfuscation finally giving way to decisive and bold decision-making behaviour. Within days, President Bush had authorised a full interagency review process and fired the individual most closely associated with the status quo strategy, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. “Basically the day after the election it’s as if all of a sudden the windows had been opened and fresh air is coming in,” a senior official recalled. The minutes of key subsequent National Security Council meetings show that the president repeatedly asked if more troops were needed, rejected alternative proposals for an accelerated transition plan and called instead for “radical action” designed to achieve “victory.” In opting to surge, Bush overruled virtually the entirety of the military chain of command. Only now, as a lame duck newly freed of electoral constraints, could he double down on his commitment to Iraq. Having kicked the decision repeatedly into the long grass while the campaign season remained “hot,” Bush recalled in his memoir that he could finally take what he understood would be “the most unpopular decision of my presidency.”

What lessons can we draw from this episode?

While we all may have some intuitive sense that elections “matter”, exactly how and when the domestic political calendar shapes wartime decision-making remains poorly understood in an otherwise rich literature on the domestic determinants of foreign policy. By paying greater attention to the electoral context and unpacking the specific mechanisms behind decision-making, it is possible to get a better understanding of the limitations placed on presidents by the electoral cycle.

As the 2020 campaign enters prime time, we can be sure of one thing: any decision involving the use of force overseas will be taken with one eye on November.

This post is based on the author’s recently published article, “Presidents, Politics and Military Strategy: Electoral Constraints during the Iraq War,” (Winter 2019/20) in International Security.