On 11 February 2020, Arvind Kejriwal led the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) to an emphatic win in the Delhi state elections, banking 62 out of 70 assembly seats. The result has been touted as a resounding rejection of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) divisive and vitriolic campaign. The elections saw BJP ministers threatening with statements such as, “shoot the traitors” and inciting the crowds by saying “they [Muslims] will rape your daughters.” This aggressive and violent patriarchal posturing hurt the BJP who have been reduced to 11.4% of the State Assembly. Female voters in particular played a pivotal role in this dramatic result, as they shifted en masse to AAP just months after the BJP swept the national elections.

Women Reject BJP

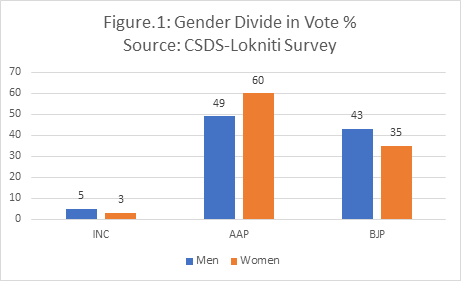

According to a post-poll survey by CSDS-Lokniti, the majority of the gap between the vote-shares of BJP and AAP came from female voters. While 60% of the female electorate voted for AAP, only 35% voted for BJP. The male voter percentages were 49% and 43%, respectively for AAP and BJP.

Two important observations can be made from these numbers. One, the AAP’s victory hinged on the female vote, and the election result would have been dramatically different without their active participation. Second, these numbers dispelled the myth that Indian women vote along the lines of their husbands and do not have their own electoral preference. As the gender gap indicates, many women voted for a different party than their partner.

Female Participation is Increasing

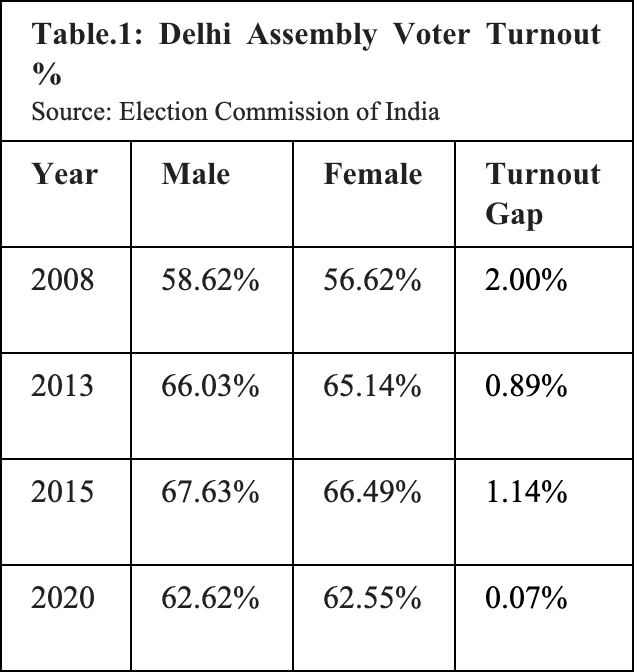

In general, female political participation nationally has been on the rise in recent years. In the Lok Sabha (Central) elections in 2019, female turnout was at a record 68% with the lowest gender voter-turnout gap in a national election. A similar trend held true in the Delhi state elections. The gender turnout gap was reduced to a historic low of 0.07% (Table.1).

Aside from just turnout, this election highlighted the active role of young women in the street protests against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which excludes Muslim migrants from a fast-track citizenship programme. Women were seen leading the protests, protecting fellow male protestors, handing roses to police officers, and serving as the symbol of resistance. While this was not the first time that women were leading mass demonstrations in India, the pictures and videos that emerged out of the media coverage coinciding with the state election magnified their voices.

The BJP failed to connect with the concerns that these protestors were raising and sought to discredit them. The narrative that these people were first time protestors who do not understand the politics was a gross misrepresentation of the reality fuelled by the BJP and mainstream media houses. This electoral defeat was a price the BJP had to pay for that.

Female Representation still Remains Low

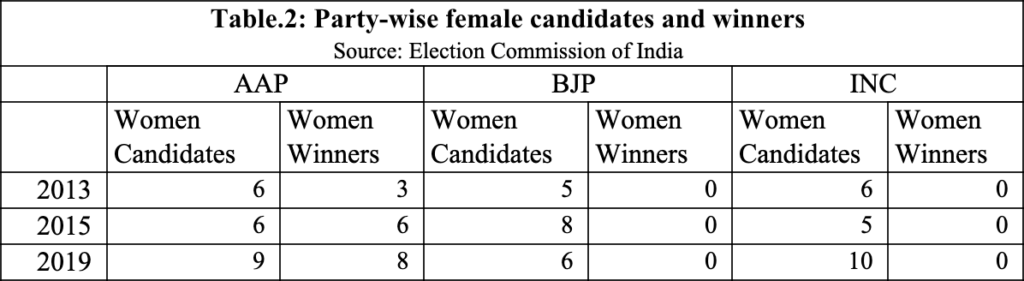

Still, it would be a mistake to think that the AAP has a spotless record on gender. Despite women serving as leading activists, the political parties, including AAP, still failed to include more women in party politics. In the newly elected Delhi Assembly, only 8 out of 70 (11.43%) of legislators are women. The fault lies not with the women but with the political parties that are still hesitant to nominate women.

Table.2 has the number of women that the major parties nominated and how many of them won. The maximum nominations were given by the Indian National Congress (INC), still only 14.28% of the total. The AAP, despite its swell of female support, only gave 12.86% of the total tickets to women. One of these nominees for the AAP was Atishi Marlena, a former Rhodes Scholar and the backbone of the education revolution in Delhi. Despite having such talented women in their ranks, the AAP is a long way from giving fair representation to women.

Why Parties Should Give More Tickets to Women?

For political parties to be successful in the future, they will need to realize the many advantages of nominating women. First, this election made it clear that women vote differently from men and have different political profiles. For example, the violent and aggressive campaign by the BJP without focus on development clearly did not resonate with the women of Delhi. If the political parties want to attract women voters, they need to be able to connect with issues that women actually care about and try to represent their demands. An important step in this direction will be to nominate more women to contest elections.

Political economists have argued that the identity of a legislator matters in affecting policy outcomes. Women leaders specifically have been known to take initiatives that benefit more women. Duflo & Chattopadhyay (2004) have argued that having female politicians at the local (panchayat) levels in India improves water infrastructure, which directly benefits women who earlier had to travel distances to collect water. Based on this, it can be argued that if the political parties field more women candidates, they begin to see their party’s policy efforts align more with women voters’ preferences, helping them capture more women votes in the process.

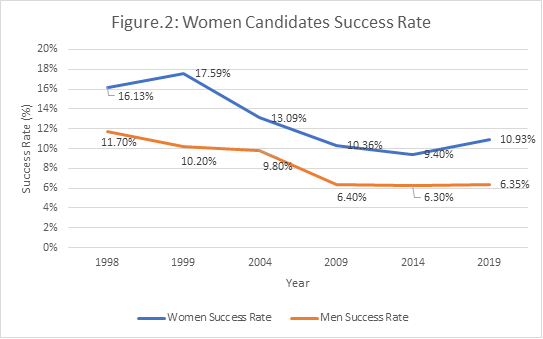

Another advantage of having more women candidates is their winnability. National election results have shown (Figure.2) that women have consistently outperformed men in terms of converting a seat if given a ticket to contest. About 10.93% percent of women contestants won their election while only about 6.35% of men contestants were able to win in the 2019 national elections. Besides this, it has also been shown that women are more competitive as the average winning margins of women generally tends to be higher than men.

With increasingly more proactive women voters shaping the political discourse of the country, the political parties in India need to re-evaluate their inadequate involvement of women in the party politics. Even if party leaders are not motivated by arguments about the value of fair representation, it will be hard for them to ignore the electoral benefits of increasing the role of women in their party.