In early May, the international community held its breath as China’s Long March 5B rocket plummeted uncontrollably back to earth. While the debris landed safely in the Indian Ocean, silencing concerns about a potentially dangerous impact, the increasing frequency of uncontrolled re-entries highlights the importance of state responsibility in safely disposing of space debris. This is not the first time China neglected to dispose properly of its orbital debris. A similar incident occurred this time last year when an out-of-control Chinese rocket–and the largest human-made object ever to return to earth uncontrolled from space–dropped debris on Cote d’Ivoire and in the Atlantic Ocean. While most debris disintegrates upon atmospheric re-entry, some components with higher melting points can persist and penetrate past the earth’s atmosphere, posing a major risk to those below. In light of these incidents, the international community faces a growing need to discuss the space debris problem not just in the context of uncontrolled re-entry but also for routine space operations in orbit.

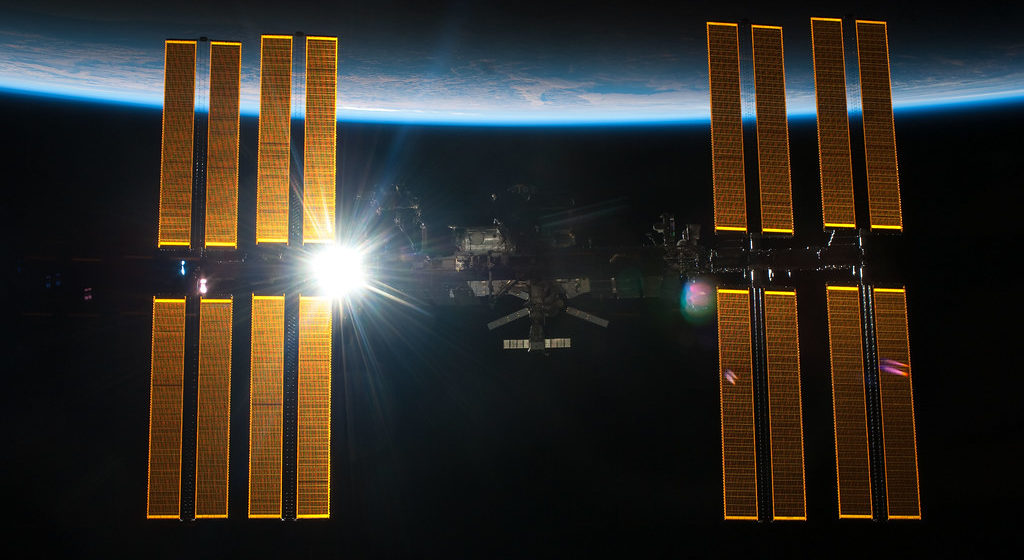

As modern life has become increasingly dependent on outer space infrastructure, the amount of technology in space has proliferated. While we do not directly engage with satellites, if disrupted, the impact can be catastrophic. For example, satellite infrastructure supports GPS navigation and the tracking of natural disasters. Space systems also support key military operations like reconnaissance, surveillance, and position navigation. Space debris directly undermines the safety and security of these space systems. It is indiscriminate and, if a collision occurs, can cause irreparable damage to operational satellites, rendering them unable to perform these critical functions.

The European Space Agency’s Debris Office estimates that there are nearly 128 million debris objects the size of a staple or smaller in space, each capable of causing significant degradation to a satellite upon collision. To get a better understanding of the threat space debris poses to operating space systems, this model created by University of Texas scholar Moriba Jah graphs close encounters between satellites, debris, and natural objects in orbit. U.S. General Hyten, then the Commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, noted in 2019 that he “did not want more debris” in space, continuing that “if we keep creating debris in space,” we will progress to the point where we cannot operate satellites, “having to manoeuvre [them] all the time to keep [them] away from debris.” Alarmingly, as states increase their launches into space and companies propose mega-constellations (a group of satellites consisting of hundreds of even thousands of individual spacecraft), the outer space environment will only become more congested, contested, and competitive. The international community needs to begin discussing these concerns not just in the context of the re-entry of space debris, but in the far more frequent repositioning manoeuvres required for satellites to operate.

Given its importance, are there any mechanisms that exist currently to resolve or mitigate the space debris problem? Thankfully, there is room for optimism. Some existing legal instruments create mechanisms for recourse in cases where a state faces harm because of re-entering space debris. For example, in 1978, the Soviet nuclear satellite, Cosmos 954, crashed over Canada, scattering radioactive material over nearly 124,000 square kilometres. Later that year, Canada presented claims under the Liability Convention, and the issue was resolved amicably with the Soviet Union paying reparations. In the case of China’s plummeting 5B rocket body, if it had hit a state and caused damage, the Liability Convention could be called upon to force the responsible party (China, in this case) to pay for damages. While this avenue exists for damage after the fact, the Liability Convention only works after an incident has occurred.

Additional mechanisms must be developed to target the space debris problem more proactively. For example, the international community drafted a series of proposals to target space debris at its source. The United Nations Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, despite their non-binding nature, offer a useful framework for proper behaviour in outer space, including limiting the probability of collisions in orbit and the creation of debris during normal operations. Other options could include active debris removal systems, which forcibly collect and remove space debris from orbit. For example, the European Space Agency has proposed an active debris removal program to stabilize the proliferation of space debris while requiring more stringent regulations for future launches that comply with post-mission disposal guidelines.

Regardless of these measures, current state behaviour, epitomized by the most recent re-entry of China’s 5B rocket, indicate the need for even stricter frameworks that force states to take this problem seriously. For example, China’s 2016 White Paper, which outlines the country’s stances on key space issues, emphasized its involvement in the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee and other international organizations as well as its improvement in space debris monitoring and collision prevention. Even with these national guidelines, the country remains a key–but not only–offender in space debris proliferation. Countries must realize that issues in space cannot be solved or coordinated on a national basis. Space debris affects all states in space and, in the cases of uncontrolled re-entry, places people and property at risk. Given the pervasiveness of the issue and the capabilities at stake, the international community would benefit by paying closer attention to this problem.

This work is the author’s own and does not represent the views of the U.S. Government, Department of Defense, or the United States Air Force.