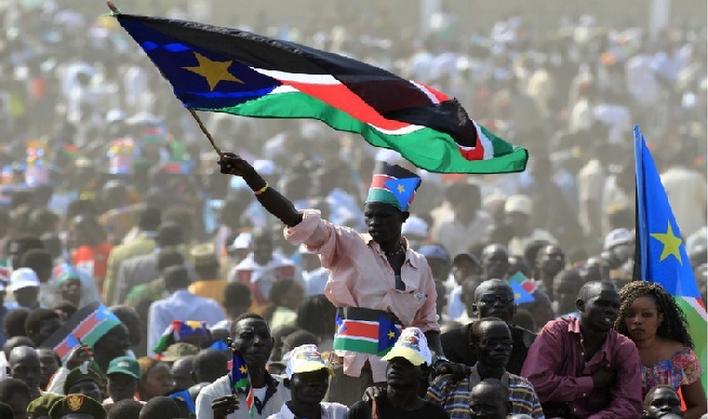

South Sudan: Uganda’s intervention may provoke a regional war

A few days ago, I discussed on Radio France International the collapse of the cease-fire and resumption of open war between the beleaguered South Sudanese government of President Salva Kiir and the rebel forces led by former Vice-President Riek Machar. The violence in South Sudan has since December 2013 claimed the lives of more than 10000 people- a death toll that is rapidly rising as diplomatic efforts have failed to broker a short-term cessation of hostilities, let alone a longer term political solution. The massive intervention of the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF) with thousands of infantrists, tanks and helicopter gunships has, for the time being, saved President Salva Kiir and the Southern Sudanese capital Juba but risks triggering a wider regional crisis that could see Sudanese and Eritrean involvement and would bring back echoes of the devastating regional wars and proxy conflicts of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s during which millions of people perished.

Why a ‘water war’ over the Nile River won’t happen

Is northeastern Africa heading for a bloody “water war” between its two most important countries, Egypt and Ethiopia? Judging by the rhetoric of the past two weeks, one could be forgiven for thinking so.

Ethiopia’s plans to build a multibillion dollar dam on the Nile River spurred Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi – whose country lies downstream from Ethiopia – to vow to protect Egypt’s water security at all costs. “As president of the republic, I confirm to you that all options are open,” he said on Monday. “If Egypt is the Nile’s gift, then the Nile is a gift to Egypt… If it diminishes by one drop, then our blood is the alternative.”

The following day Dina Mufti, Ethiopia’s foreign ministry spokesman, said that Ethiopia was “not intimidated by Egypt’s psychological warfare and won’t halt the dam’s construction, even for seconds”.

Morsi’s bellicose warnings followed the suggestions of leading Egyptian politicians on television last week that Cairo should prepare airstrikes and send special forces to uphold its God-given right to the lion’s share of Nile waters. The Ethiopian government of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn has signalled that it is not impressed and that it will carry on with work on the multibillion dollar Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam – a move seen by some as raising temperatures further, possibly triggering the “water wars” that pessimists have long predicted will characterise the geopolitics of the 21st century.

China’s Positive Spin on Africa

The lightning growth of Chinese media is part of the dramatic expansion of the presence of Chinese diplomats, peacekeepers, commercial actors (state-owned or private) and ordinary citizens that has been transforming the African continent in the last 10-15 years.

Politics and Islam: A religious movement in Sudan has become critical of Bashir and the ruling party

Last weekend, I discussed on Radio France International the meeting in Khartoum (Sudan) of thousands of politico-religious militants with strong links to the government: the general conference of the Islamist movement known as Al-Harakat Al-Islamiyyah is the most important political rally in the country of the last 10-15 years. Reformers among them believe Sudan’s military-Islamist regime has drifted from its revolutionary roots. Some are even calling on President Omar al-Bashir to leave office.

Zenawi: The titan who changed Africa

At 23:40 local time, the Ethiopian prime minister was declared dead, the consequences of a mysterious infection that had international policymakers and Ethiopian citizens concerned about his health for weeks. The disappearance of the man who had ruled from Addis Ababa for the past two decades – having come to power through guerrilla war against the communist Derg regime – has unleashed speculation regarding likely successors and an internal power struggle inside the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Less attention is being paid to the regional fallout of the death of this African titan – though the consequences of Meles’ demise for the future of millions of Africans could be profound. The food crises of the 1980s and hundreds of thousands of dead …

Dambisa Moyo’s Resource War Argument is Flawed

Bestselling author, financial economist (and Oxford alumnus) Dambisa Moyo argues in her new book that the rise of China is generating unanticipated consequences for the international system and that no one — bar the Chinese Communist Party — is actively thinking about how to handle the long term fallout of these seismic shifts. I debated some of these ideas with her on Radio 4’s Today Programme a couple of days ago. One of Moyo’s controversial arguments is that China’s ascendency doesn’t just put tremendous pressure on commodity markets, but is likely to represent such a big demand shock that supply of key resources simply can’t keep up. The consequence, for Moyo, is then that as countries — and the planet …