Time is running out for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

In 2013, the European Union and the United States launched negotiations for a comprehensive trade agreement (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, TTIP). TTIP’s objective is to facilitate market access for goods and services across the Atlantic by cutting tariffs and trade restrictions (like the Buy American Act), harmonizing regulatory standards, and setting common trade rules, including on custom policies and protected geographical indications.

The agreement is negotiated in a difficult situation. Europe’s weight in the global economy is declining, whereas the US has recovered from the crisis and is striking a parallel deal with the ASEAN countries in the Far East.

Europe’s economic prosperity depends on trade more than that any other region’s in the world. International trade (import and export) accounts for 87% of EU GDP (against 30% in the US, and 50% in China). But what TTIP is about is the future, not the present. This is the last opportunity for the EU and the US to set the production, environmental, investor and consumer standards for the global economy.

The first EU election fallout

Europe’s politics and the debate about the future shape of the Union dominated the 2014 campaign season for the European Parliament. As a result, the line between domestic and European politics has blurred or even disappeared and it has become clear that party politics at EU level will transform the functioning of European institutions in the coming years. The three main European political parties have already launched frontline candidates for the Commission presidency and committed to supporting them in the European Council and Parliament. Nevertheless, the coming post-electoral wrangling for key EU positions will reflect the strengths and weaknesses of national heads of governments and their respective countries. In France, the ballot count put the establishment in a state of …

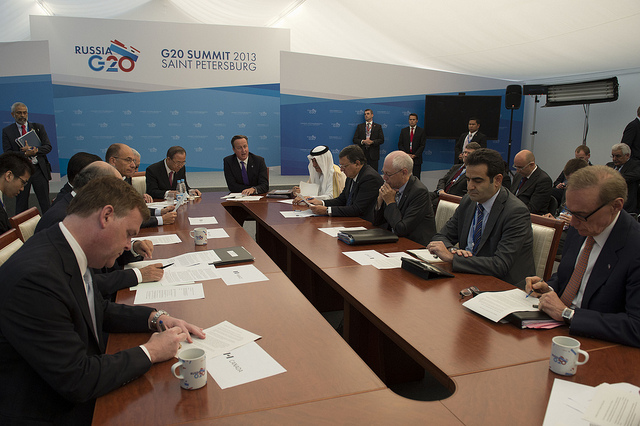

Growth, international trade and energy at the Russian G20

The war in Syria dominated media and diplomatic attention at the G20 in early September in St. Petersburg. At the actual summit, however, the agenda covered mainly macroeconomic and financial issues. Inaugurated in 1999 as a meeting of finance ministers from developed countries and emerging economies, the G20 has turned into a top-level summit coordinating the global response to the financial crisis after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. The G20 summits in Washington (2008), London and Pittsburgh (2009) re-financed the IMF ($500 billion), and established the Financial Stability Board to stabilise the banking system and derivatives markets. More difficult and less successful were the concerted efforts, from 2010 onwards, to couple fiscal austerity with structural adjustments between trade surplus countries (exporters such as China and Germany) and trade deficit countries (importers such as the US and Italy).

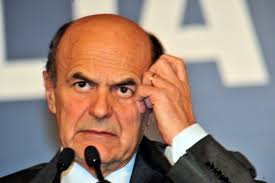

The Italian Left: Reform and win, or perish

The general election has put the Italian Left in a state of shock. In December, the coalition led by Pierluigi Bersani had a fifteen points lead in the polls, while more than three million people turned up to vote in the leadership primary election. But last week’s election made that seem a long time ago. The final vote produced a new political reality: a hung parliament and the bitterest defeat for the Left in 20 years.

The vote spelled frustration at a whole generation of politicians. The parties which stood for parliament in 2008 collectively lost roughly 13 million votes. The centre-right parties lost more than half of their votes (about nine millions), even though Berlusconi managed a spectacular comeback by leading an unapologetic campaign. It proves that he can still dominate the debate. Mario Monti’s centrist coalition intercepted a further 2.5 million votes, mainly from the centre-right. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, lost 3.5 million votes compared to the last election, which also resulted in defeat. After months of successes in local elections and in the polls, the party portrayed itself as the only responsible force in a country in disarray. But just like Neil Kinnock in 1992, Bersani took the victory for granted. He ran a political campaign where the main objective seemed to reassure the party militants that a victory was finally at hand.

Neither Left nor Right: The rise of populist movements in Italy

When an economic crisis combines high youth unemployment and an impoverished middle class, there is a real risk of a rise in right-wing extremism. But the left/right divide does not always help to understand European populism.

The Italian case is a particularly interesting one. After Berlusconi resigned in disgrace, the main two parties (Berlusconi’s People of Freedom-PDL and the centre-left Democratic Party-PD) were left with no choice but to support a ‘truce government’ of non-politicians and technocrats, led by Mario Monti. This unlikely arrangement froze the parliamentary majority.