Africa’s public debt burden has doubled from 2010 to date. Data from the International Debt Statistics Data as of December 2022 shows that African countries owe $ 644855.2 billion (USD).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank consider 22 low-income African countries to be either in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress as of November 2022. Debt distress in this context means a country is experiencing difficulties in servicing its debt. A high debt burden could risk the continent’s economic growth, development, and climate investments. The additional global economic downturn and falling commodity process could compound the issue for countries on the continent. While there is no immediate threat of systemic and financial collapse due to debt burdens, there is a need for urgent action to reverse this trend. This is because the current debt issues prevent African countries from dealing with other pressing development issues. For example, an increasing debt burden is preventing countries like Zambia from protecting themselves against the worst effects of climate change. It will be impossible for African countries to work towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals if they are unable to access finance and service debt.

Understanding Africa’s Debt Sustainability Issue

Data from the World Bank shows that 49 African countries owe 39% of their debt to multilateral institutions, 35% to private creditors (excluding Chinese private creditors), and 12% of the debt burden on the continent is owed to China and Chinese lenders. In 2021, private lenders charged 5% interest rates while China and multilateral lenders charged 2.7% and 1.3%, respectively. This spread of creditors makes it hard to navigate issues of debt restriction. African countries looking to discuss easing the debt burden face the uphill task of coordinating creditors with varying interests and willingness to cooperate. Creditors are often unwilling to restructure debt if they believe it will serve the interests of other creditors.

At the end of 2021, Angola, Djibouti, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sudan, Tunisia and Zambia, Cabo Verde, Mauritius, and Seychelles had external debt levels of more than 75% of GDP. Debt-to-GDP Ratio compares what a country owes with what it produces. It is a reliable indicator of a country’s ability to repay its debts. The higher the debt-to-GDP ratio, the less likely the country will pay back its debt and the higher its risk of default, which could cause a financial panic in the domestic and international markets. A study by the World Bank found that countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios exceed 77% for prolonged periods experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. Pointedly, every percentage point of debt above this level costs countries 0.017 percentage points in economic growth. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in emerging markets, where each additional percentage point of debt over 64% annually slows growth by 0.02%.

There is room for optimism, however. As of 2022, the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) provided some relief for distressed economies. The DSSI allowed poorer countries to fight COVID-19 without taking on additional debt. Nevertheless, the initiative has ended, and has been replaced with the ‘Common Framework for Debt Treatment beyond the DSSI.” Also, as of 2022, the IMF has allocated Africa $33 billion in special drawing rights (SDRs), providing an immediate liquidity boost without adding to the debt portfolio.

2023 will provide a unique opportunity for African countries and their lenders to agree on the best way to proceed without taking on more debt or worsening already precarious economic situations. The issue of debt sustainability on the continent is complex and requires a multifaceted approach to resolve.

Chinese Debt in Africa

China has become Africa’s biggest bilateral lender, holding over $73 billion of Africa’s debt in 2020 and almost $9 billion of private debt. This increased lending to the continent has drawn significant attention and criticism. Accusations of debt trapping have been a critical feature of the Sino-African relationship.

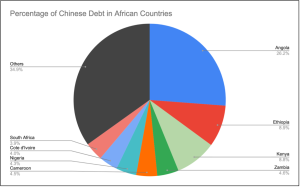

Chinese debt varies widely across the continent. Chinese loans are critical in only a subset of Africa’s 54 countries. Data from Boston University Global Development Policy Center shows that Angola and Ethiopia are the two leading recipients of Chinese loans. China loans on the continent have driven infrastructure and development projects.

Interestingly, Beijing has grown more cautious about lending on the continent as the prospect of default looms. The eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation (FOCAC) held in November 2021 saw Chinese investment pledges cut for the first time—dropping from US$60bn pledged at the seventh meeting in 2018 to US$40bn in 2021. China’s two central policy banks, China Eximbank and China Development Bank, have taken on increasingly hardline lending terms. While China did not solely cause Africa’s debt distress, it is a crucial stakeholder in finding a solution. Africa’s creditors must put aside geopolitical issues to resolve this issue across emerging markets on the continent.

China’s Efforts Towards Debt Restructuring in Africa

Resolving Africa’s debt sustainability will require the cooperation of China, African nations, Paris Club members, and other key stakeholders.

On the 11th of January 2023, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement asserting China’s commitment to helping Africa’s debt burden by joining the Group of 20 (G20) Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and signing various agreements. So far, China has agreed to consider debt restructuring on a case-by-case basis. This is an attempt to continue protecting its commercial and strategic interests. According to Johns Hopkins University’s China Africa Research Initiative (CARI), China wrote off at least $3.4 billion of debt between 2000 and 2019, almost all interest-free loans to African countries. As of 2022, China has forgiven 23 interest-free loans in 23 countries. While this was seen as a positive step, interest-free loans only make up a small fraction of Chinese loans on the continent. There is a need for more negotiation and action.

One potential route for resolving this issue could be taking action to fix the Common Framework for Debt Treatments. In 2020, the G20 announced an agreement in principle of a Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). The framework aims to address the problem of unsustainable debts faced by many countries in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2023, the common framework is struggling to maintain its credibility. There is a need to fix some of the technicalities, including how cases are dealt with; private creditors could provide relief and enforcement of the rules.

More comprehensive support from the West and China is required for African countries, especially those at high risk of debt distress. An ideal plan for resolving the current situation would have several components. First, a dialogue among all stakeholders, including the G7, China, African countries, and others involved in lending on the continent must be fostered. Such dialogue needs to establish an action plan to resolve the current issue of unsustainable debt burdens and to ensure that countries do not reaccumulate more debt in the future.

Second, cooperation among lenders such as China and the West must be established as this will ensure honesty and transparency in the process. Overall, multilateral approaches of this nature could create a path to ensuring continued international agreement.