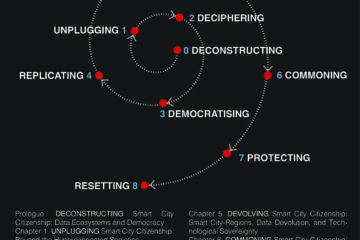

Smart City Citizenship: A Techno-Political Review (of Cities and Nations)

COVID-19 has hit European citizens dramatically, not only creating a general risk-driven environment with a wide array of economic vulnerabilities but also exposing them to pervasive digital risks, such as biosurveillance, misinformation, and e-democracy algorithmic threats. Over the course of the pandemic, a debate has emerged about the appropriate techno-political response when governments use disease surveillance technologies to tackle the spread of COVID-19. Citizens have pointed out the dichotomy between state-Leviathan cybercontrol and civil liberties. Moreover, the giant technological flagship firms of surveillance capitalism, such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook, have already assumed many functions previously associated with the nation-state, from cartography to the disease surveillance of citizens. But particularly, amidst the AI-driven algorithmic disruption and surveillance capitalism, Smart City Citizenship sheds light on the way citizens …

City-regional small nations beyond nation-states

With separate histories and political-cultural traditions, the UK and Spain do not have the same nation-state DNA. Yet both face issues over regional independence. While the UK Government has legitimised the Scottish Government and supported the Scottish Independence referendum as a highly democratic exercise, Spain stands out as remaining normatively inflexible without, so far, even contemplating any dialogue with the presidents of the Catalan and Basque Autonomies.

Other EU nation-states accept the UK’s approach to sort out regional and nationalistic claims democratically. But Spain has been avoiding the demands of the Catalan and Basque institutions and citizens on the basis of both historic and more recent episodes of political unrest. As a result, it seems impossible to open any discussion about the devolution claims of city-regional small nations, particularly in terms of devising an internal, alternative and re-scaled configuration of Spain as a nation-state, which would involve modifying the 1978 Constitution. In the case of the Basque Country, this is presented as the least likely outcome as political violence in the region has been both a major obstacle and also a source of inertia. Nevertheless, ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna)[1], announced a ‘definitive cessation’ of its campaign in 2011 and, therefore, should welcome any kind of democratic implementation that involves devolving powers to the Basque Country.

But are there any remarkable differences between EU nation-states such as the UK and Spain?

Indeed, I think there are plenty of them.