In case Scotland votes no, how should we regulate future independence referendums?

In a few months time Scotland will vote on independence. In my last post on the topic I discussed some of the consequences of a yes vote: the problems that would be raised around the currency, Scotland’s membership of the EU, and, more generally, the difficulties presented by the tight time-fame set by the Scottish Government for negotiation. That post should have given wavering ‘yes’ voters pause for thought; the path to independence is harder and riskier than the Scottish Government’s optimistic White Paper claims. In this post I will discuss one of the consequences of a no vote: its implications for subsequent independence referendums. This post should, perhaps, cause wavering ‘no’ voters to reflect. The independence referendum is, or should be, a once in a generation chance to leave the Union. It would be a mistake to assume that a second referendum will be held any time soon.

There are problems with constitutionalising a right to secession. In a classic article, written as the states of Eastern Europe were recasting their constitutional orders in the early 1990s, Cass Sunstein argued that constitutions should not normally incorporate a right to secede. Sunstein argued that such rights inhibited the creation of a united, effective, state. The constitutional possibility of secession might encourage regions to consider independence on a regular basis, and, on the other side of the equation, the remainder of the state will be aware of secession as an ever-present possibility. As Sunstein argues, this may inhibit long-term planning: why should the state engage in projects that principally benefit the region, knowing that the region might leave at anytime? And when the project benefits the whole state, but requires regional cooperation, how can the state be sure of this support? More darkly, Sunstein warns there is a risk of blackmail. The region can use a threat of secession to put unfair pressure on the remainder of the state. Finally, as Sunstein points out – and as we have reason to know all too well – questions of secession tend to stir emotions more deeply than other political questions. The intemperate character of debate around the issue can, in itself, harm the capacity of the state to act as a coherent unit.

Same-sex marriage and the law: a Q&A with Oxford’s Iain McLean and Scot Peterson

I recently sat down with Dr Iain McLean and Dr Scot Peterson to discuss their new book, Legally Married: Love and Law in the UK and the US, which discusses the issues of same-sex marriage in both countries.

I found your book very interesting and though it addressed a very topical issue whilst providing a wealth of historical information and context. Could I start by asking what you think is driving the apparently accelerating legalisation of same-sex marriage worldwide?

Iain McLean: Which is the chicken and which is the egg? In North America, Latin America, and west/central Europe, social attitudes are changing further and faster than on any other moral issue that surveys have ever tracked. And politicians are responding. So are courts. Although judges like to believe that they are above politics, they would think hard about handing down constitutional interpretations that put them wildly at variance with public opinion.

There is a possible ratchet effect too. The US Supreme Court’s decision in Windsor v. US, in June 2013, holding that denial of federal tax benefits to same-sex widow Edith Windsor, which she would have received if her spouse had been male, was unconstitutional, has speeded up the process of legalising same-sex marriage in New Jersey, and may do so in other US states as well.

Osborne’s proposed spending cuts after 2015 would be unusual – but not unprecedented

At the beginning of the year, George Osborne announced his intention to push on with spending cuts should the Conservatives be re-elected in 2015. We looked at previous episodes of UK expenditure cutbacks and find that the current proposals are no more extreme. However, the Scottish referendum could mean the stakes in spending-cap politics prove to be higher this time round.

At the beginning of this year the Chancellor, George Osborne, announced a proposal to impose spending cutbacks during the next Parliament. The plan announced was for £25bn of spending cutbacks over the period 2015-17 to deal with the UK’s continuing deficit. That deficit-cutting strategy appeared to rely largely on spending cuts (mostly directed at working-age welfare) and little if at all on tax increases.

The table below compares the outcomes of eight selected episodes of UK spending cutbacks over a 90-year period, including the current coalition government’s spending record based on reported figures up to 2013. It also compares those eight historical episodes with the plans announced by Osborne for further spending cuts before and after the UK general election scheduled for 2015, based on the assumptions (a) that those plans would be fully implemented as announced and (b) that the OBR forecasts of GDP up to 2017 proved to be broadly correct. Both assumptions are of course highly contestable.

Scottish Independence: Some known unknowns

If the Scots vote Yes on 18 September 2014, they do not know what they will get, apart from the departure of Scottish MPs from Westminster. To borrow Donald Rumsfeld’s useful phrase the remaining terms of independence are ‘known unknowns’. The Scottish negotiators must enter discussions with several counterparties, the main ones being the European Union, NATO, and the rest of the United Kingdom . Let me discuss seven of these ‘known unknowns’.

Scotland: What will happen after the vote

At 650 pages Scotland’s Future is not a light read. It stands as the Scottish Government’s manifesto for a yes vote in the independence referendum. The volume ranges from profoundly important questions relating to currency and Scotland’s membership of the European Union, right down to weather-forecasting and the future of the National Lottery. Though it is likely many copies of Scotland’s Future will be printed, it is unlikely many will be read from cover to cover. Its authors probably do not regret its length: by its very heft, the volume seeks to rebut claims that the consequences of independence have not been carefully thought through. This post considers the immediate constitutional consequences of a yes vote in light of Scotland’s Future. Its central argument will be that the timescale proposed by the Scottish Government for independence following a referendum is unrealistic, and may work against the interests of an independent Scotland.

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Play Episode

Pause Episode

Mute/Unmute Episode

Rewind 10 Seconds

1x

Fast Forward 30 seconds

00:00

/

Subscribe

Share

RSS Feed

Share

Link

Embed

Download file | Play in new windowIn years to come, Saturday 30 November 2013 may be remembered as the last time that a genuinely united Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland came together to celebrate St Andrew’s Day (Scotland’s official national day). With a referendum on Scottish independence set to take place in Scotland on 18 September 2014, the British state’s survival is far from certain. A majority vote in favour of independence would not result in the immediate break-up of the UK (though the Scottish National Party have recently called for full Scottish separation by March 2016 if independence is endorsed at the ballot box). But even so, it is clear that victory for the independence campaign would leave British national unity – terminally battered and bruised – as little more than a wishful façade. If the Great British edifice crumbles to the ground, what are we to make of the pieces that remain?

Polling One-off Events: How reliable are the polls on Scottish independence?

The 24th of March 2016 could be Scotland’s Independence Day if Scots vote ‘Yes’ in next September’s referendum. However, the skirling of bagpipes to herald the birth of a new nation can barely be heard in the far distance. The most recent poll shows the ‘Yes’ campaign continuing to trail the ‘Better Together’ campaign by 9%, with 38% of voters intending to vote ‘Yes’, 47% inclined to vote ‘No’ and 15% undecided. With almost half of voters remaining in the ‘No’ camp, the future of the union looks secure. However, demographic complexities behind this once-in-a-generation referendum may make standard polling techniques unreliable.

The left-wing Radical Independence movement has presented the referendum as a ‘class conflict’ in which the rich promoted a ‘no’ vote to maintain their privilege. In reality, the battle lines are less clearly drawn. Research conducted by the eminent psephologist, Professor John Curtice, found that middle class people needed more reassurance than their working class compatriots that independence would not have an adverse effect on the country’s economy. However, if citizens could be guaranteed that they would be £500 a year richer under independence, the results would be turned on their head. If the ‘Yes’ campaign can make a better economic case for independence, or if fear of the UK leaving the EU becomes real, the economic calculus may change.

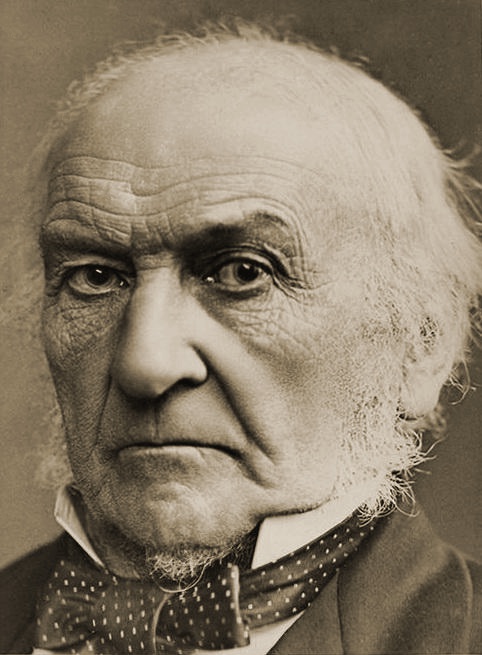

William Gladstone might have the answer to the ‘West Lothian’ question

The Commission on the Consequences of Devolution, also known as the McKay Commission, reported quietly in March 2013. Its remit had been to consider how the Commons should handle legislation that affects only part of the UK, now that domestic policy, to varying degrees, has been devolved to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It was not, however, instructed not ‘to deal with matters of finance in the context of the devolution settlements or with the representation of the devolved areas at Westminster’. This is Hamlet without the prince: finance and representation are the big unsolved questions in UK devolution. But for news about Claudius, Laertes and Polonius, read on.

The Commission examines solutions to the ‘West Lothian Question’ (WLQ) other than cutting the numbers of MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The WLQ, properly stated, relates to the powers of MPs (and in principle peers) not from a given part of the UK to alter legislation that affects only that part. In the past, it has severely affected Scotland, Wales and (Northern) Ireland. The Poll Tax was introduced in Scotland only by an Act which the majority of Scottish MPs opposed. Older examples include the blocking of Welsh church reform from 1868 to 1920, coercion Acts in nineteenth-century Ireland, and the Patronage Act (Scotland) 1711/12, violating the then recent Act of Union.

However the WLQ can now only affect England.