Russell Brand’s socialist revolution

Russell Brand, the British comedian, used a guest editorship of the 100-plus-year-old leftist magazine New Statesman last month to call for a “total revolution of consciousness and our entire social, political and economic system.” Capitalism, and the ideology that sustains it — “100 percent corrupt” — must be overthrown. He also doesn’t think people should vote, as partaking in democracy would further the illusion that a rotten system could change. It was a call, albeit chaotically phrased, for a socialist revolution.

Born into the middle class, Brand’s childhood was disturbed: his photographer father left when he was six months old, his mother developed cancer when he was eight (but survived), he left home in his mid-teens and took to drugs. He later became a star, delighted in promiscuity, married the singer Katy Perry for a year and a half and grew modestly (by star standards) rich, with an estimated net worth of $15 million and a lovely new Hollywood millionaire bachelor’s pad.

Can you buy a Police Commissioner? Spending at the 2012 Police and Crime Commissioner elections suggests it depends on the party

Just under a year ago the first Police and Crime Commissioner elections were held in England and Wales. Two weeks ago, the Electoral Commission released data on candidate donations and spending at those elections. In total candidates spent £2.1 million – an average of £11,220 each. For comparison candidates at the 2010 general election only spent £6,284 each (but this doesn’t count party spending, which was much lower at the Police Commissioner elections). Media reporting of the data tended to concentrate on the more extreme cases of candidate spending – the Conservative candidate who spent £98,751 and didn’t win, or the independent candidate who (officially at least) didn’t spend a single penny and won.

The casual observer might then be forgiven for thinking that candidate spending had no impact on the outcome of the Police Commissioner elections. However, as any good social scientist will tell you, outliers often obscure trends rather than indicate them. Campaign spending is a much studied topic in political science and the consensus is that spending more money gets more votes. One of the key insights about campaign spending is that it tends not to change voters’ minds about who to vote for but rather whether or not they bother turning out to vote at all.

The legality of military action in Syria: humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect

It now seems fairly clear that the US and the UK are set to take military action in Syria in the coming days in response to the recent chemical attacks there. The UK Prime Minister, UK Foreign Secretary and the UK Secretary of State for Defence have all asserted that any action taken in Syria will be lawful. But on what grounds will military action in Syria be lawful. As is well known, United Nations Charter prohibits the use of force in Art. 2(4), as does customary international law. The UN Charter provides 2 clear exceptions to the prohibition of the use of force: self defence and authorization by the UN Security Council. It is almost certain that there will be no Security Council authorization. In a previous post, I considered the possibility of a (collective) self defence justification for the use of force in response to a use of chemical weapons. The scenario contemplated then is very different from the situation that has emerged, and the language used, at least by the UK, does not hint at a use of force on the basis of national interest. However, President Obama in a CNN interview last week did seem to speak of self defence when he said “there is no doubt that when you start seeing chemical weapons used on a large scale … that starts getting to some core national interests that the United States has, both in terms of us making sure that weapons of mass destruction are not proliferating, as well as needing to protect our allies, our bases in the region.” A justification for force on this basis would sound like preemptive self defence in a way that is very close to the Bush doctrine. I find it hard to see the Obama administration articulating a legal doctrine of preemptive self defence claim in this scenario.

The constitutional inheritance of the royal baby: a speculation

It might be thought that there would be little need for a post on this blog about the arrival of the royal baby. The new Prince of Cambridge – Your Highness, to his friends – is unlikely to play a significant constitutional role for sometime to come. I found myself wondering, though, what the constitutional situation will be when, and if, he finally comes to the throne. So, here is the post I plan to write in 2075 – and the way academic pensions are going, I will probably still be working then.

To some, it may come as a surprise that Britain continues to be a monarchy. We escaped, or missed, the tide of republican constitutional reform that followed the death of Queen Elizabeth in the middle third of the century. Australia and Jamaica were the first to go, followed, like a line of falling dominos, by Canada, and then by New Zealand. Other territories followed suit, with most adopting an elected head of state or – more simply still – combing the role of head of state with that of prime minister. However, it is still the case that the sun never fully sets on our new King’s realms: some small territories decided, for economic and foreign policy reasons, to retain the royal connection. And the Privy Council, acting as their highest court, still provides a useful guarantee of legal certainty to the owners of the many corporations nominally residing on these islands. Like these micro-realms, we in the United Kingdom have retained our monarchy. This is only partly through choice: the moment has never seemed quite right for a public discussion of the wider issues raised by an hereditary head of state, there always seems to have been more important matters to worry about. It could well be said that it is apathy, rather than a commitment to royalism, than has allowed the institution to last this long.

The New Labour That Wasn’t: Lessons for Miliband

Labour currently faces a period of challenging redefinition. New Labour is emphatically over and done. But as New Labour recedes into the past, it is possible to speak of a road not taken – the ‘New Labour That Wasn’t? And what relevance does it have for Labour today?

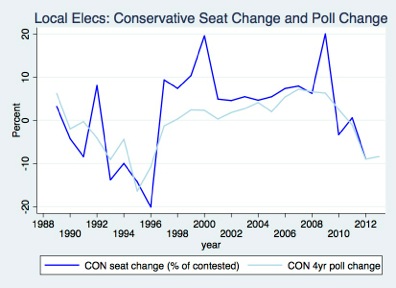

What do the polls tell us about local election results?

While some ask what local election results tell us about the state of the parties and prospects for the next general election, it is also important to consider how national party popularity affects the fortunes of candidates in local government elections. Local elections are often said to be about local issues but actually most of the changes over time in shares of council seats won the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats can be accounted for by changes the popularity of these parties at the national level.

Plans for regional banks are a radical leap for Britain

Outside the banking sector and its critics, not everyone grasped the radicalism of Ed Miliband’s announcement a few weeks ago that the next Labour government will establish a network of regional banks. But this was policymaking at its best, signalling a commitment to radically reform the relationship between finance and the real economy and a determination to make Labour the party of small businesses across the nation.

The British banking system is astonishingly uncompetitive: 89 per cent of all our businesses are dependent on the five major clearing banks. Yet over the last 30 years these banks have become disconnected from the needs of these businesses, seeking quick profits in the City and in the property markets rather than long term investments in the industries and regions outside the southeast. Duncan Weldon has calculated that, in the decade before the crisis, 84% of the money lent to British residents by British banks went into property and financial services.

‘Making Thatcher’s Britain’: an interview with Robert Saunders

Robert Saunders is co-editor (together with Ben Jackson) of Making Thatcher’s Britain. He teaches History at Jesus College, Oxford, and Politics at Lincoln College. I really enjoyed Making Thatcher’s Britain. Can I start by asking a biographical question about Thatcher before we get to the book — how did she come to lead her party in 1975? Was it a result of a careful campaign or happenstance? There was a degree of good fortune to the affair. If Ted Heath had resigned a year earlier, or if Keith Joseph had run in 1975, Thatcher would not have been a candidate. She won partly because of a brilliant campaign organisation, and partly because she was the only one willing to challenge such a dominant leader. But …