The Metropolitanisation of Nationality? City-regions, autonomy and the territorial state

The recent plebiscite on Scottish independence has triggered a much wider debate in the UK about the organisation of state power in institutional and territorial terms.

In particular, the role and economic position of the main cities vis-à-vis the state have raised headlines about ‘cities going independent’, such as ‘Devo Met’ (The Economist, 25 Oct 14). This not only continues the strong focus on the economic dimension of statehood and its territorial and institutional manifestation, but also that of identity and the sense of community (commonality). No longer, so it seems, does nationality operate automatically through the ‘nation state’ as a territorial and governmental entity. Instead, metropolitanism is encouraging, perhaps requiring, a ‘reterritorialisation of politics’ (Sellers and Walks, 2008). This growing emergence of an urban (metropolitan) dimension to national (and international) discourses on shared values, imaginations and common purpose has come to challenge the nationalisation thesis formulated as part of ‘political modernisation’ (Hofferbert and Sharkansky, 1971), and its primary focus on territorial states as expressions of an existing and cohesive civil society, or as ‘nationalisers’ seeking to shape a national identity (Brubaker, 1995). This once prevailing thesis propagates national contexts as dominant, hegemonial conditioning factors which reach across states, including regional and local identities and discourses, whether urban or not. The understanding of nationality has thus been viewed from a top-down perspective of discursive nationality, and corresponds with the territorial view that cites, being down the scalar hierarchy from the state, are automatically an integral part of that – bigger – entity – geographically, institutionally and discursively.

Such, in effect, triple hierarchisation – where territory, institutional power structures and discourse of identity and belonging (communality) sit in parallel hierarchical arrangements – is now being challenged by a growing urban/metropolitan voice stepping out of the seemingly homogenous sonority of a national discursive ‘backcloth’. This may appear as a reverse step to the integrative, even homogenising, effects of nationalising politics (Caramani, 2004), seeking to overcome spatial and societal differences in identities and sense of belonging. From such a (conventional) perspective, states are seen as the ‘natural’ rallying points of national discourses of self-determination and their geographic manifestation.

Between Independence & Re-centralisation: Political Innovation in an Age of Devolution

In 2014 the push for devolution became a major political issue. Scotland remains in the UK, but only after last minute bargaining devolved further powers to Holyrood. This has encouraged calls for more devolution of powers to Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and for the formation of an English parliament. George Osborne’s Autumn Statement proves that Westminster is listening. Meanwhile, MPs and local governments want more powers entrusted to local authorities. Manchester is following Bristol’s lead in appointing a mayor.

The UK is not alone in this trend. Emboldened by the experience in Scotland, Catalonia held an independence vote of its own, even if unrecognised by the government in Madrid. Legal or not, that vote may also boost efforts in the Basque Country, Bavaria and Flanders.

While these votes may prove unsuccessful, the tension surrounding them will linger. The issues depend on the contextual consequences of the increasing trend towards devolution. There are two forces operating in two different directions: on the one hand, city/regional small nations are demanding Independence from their referential nation-states, while on the other hand, nation-states themselves are re-centralising or decentralising their structures and powers.

Over the coming months, this Special Series will focus on the diverse angles to this debate by identifying and emphasising certain innovative and thought provoking case studies for the purpose of comparison.

Posts will cover topics like the re-scaling of nation-states, constitutional change, the right to decide, independence movements, the federal EU hypothesis, the Europe of Regions approach, democratic participation and civic nationalism in relation to city-regions.

Let the people speak! The state of devolution, decentralization and deliberation in UK politics

Democratic pressure is building, cracks and fault-lines are emerging and at some point the British political elite will have to let the people speak about where power should lie and how they should be governed. ‘Speak’ in this sense does not relate to the casting of votes — the General Election will not vent the pressure — but to a deeper form of democracy that facilitates both ‘democratic voice’ and ‘democratic listening’.

In the wake of the Scottish referendum on independence the UK is undergoing a rapid period of constitutional reflection and reform. The Smith Commission has set out a raft of new powers for the Scottish Parliament, the Chancellor of the Exchequer has signed a new devolution agreement with Greater Manchester Combined Authority, the Deputy Prime Minister has signed an agreement with Sheffield City Council, and the Cabinet Committee on Devolved Powers has reported on options for change in Westminster. One critical component of this frenetic period of reform has been the absence of any explicit or managed process for civic engagement even though the Prime Minister’s statement on the 19 September 2014 emphasized that ‘It is also important we have wider civic engagement about how to improve governance in our United Kingdom, including how to empower our great cities. And we will say more about this in the coming days’.

The days and months have passed but no plan for civic engagement has been announced.

In the meantime, calls for a citizen-led constitutional convention have been made with ever increasing regularity and volume.

When the mafia acts like the state. Quantifying the (bad) effect of Italian organised crime on safe waste disposal

The phenomenon of organised crime in Italy is intrinsically connected with social development and is a powerful brake on institutional performance. The power of the organised crime lies in its involvement into seemingly legal activities and in the control exercised over entire economic sectors through systematic extortion and violence.

Since the early Nineties, southern regions in Italy have experienced chronic issues of illegal disposal of urban waste, mainly due to easy access to uncultivated land, presence of caves and sovereignty of mafiosi – to use a general definition that encompasses mafia, camorra, ‘ndrangheta and other networks. When combined with inherent weakness of local administrations that turn a blind eye to illicit trafficking of waste, this poses a serious threat to local welfare, health and agriculture.

In Italy, waste management is a public service funded by revenue from waste taxes. The operational part – collection, treatment and landfilling – is performed by private companies or subsidiaries, which compete in public tenders. The regional authority, via a regional commission, sets an average value for the price of landfilled waste, while local waste operators set site-specific gate fees. It follows that the waste operator gains higher profit from the combination of higher prices and larger quantities of treated waste. Net economic benefit from waste management depends on private costs of landfill establishment, operation, and health and environmental standards; hence it is not unreasonable to say that private costs are lower if the waste operator deviates to illegal disposal – an option offered by mafia.

This generates a loss of economic efficiency; the rent from waste management activities entirely accrues to criminal networks, which often infiltrate in the tender system and bid comparatively lower prices.

What can Rwanda’s dam building tell us about its politics?

Rwanda has just completed its first Large Dam since the genocide (traditionally defined as one over 15 metres high). The Nyabarongo Dam will become the country’s primary power station and increase Rwanda’s power generation by a third. It is arguably the first singularly big development project to be completed by president Kagame’s government, and is set to be the first of many with a further four Large Dams in the immediate pipeline and the Bugasera Airport under construction. They form part of a wider effort to build large ‘modern’ infrastructures across the country, from road improvements and increased energy production to skyscrapers in the capital Kigali.

So what does this drive towards big projects entail for Rwanda? Can it tell us something about the way in which the country is run and the values of its government? This article explores aspects of Rwanda’s flagship dam project that indicate the government’s wider approach to development politics.

‘Charlie Hebdo’ and the end of the French exception

Today many are asking why Parisians have been attacked in their own city, and by their own people. But for many years the question for those following the issues of foreign policy and religion was why France had suffered so little terrorism in comparison to other European states. After the bombs on the Paris Metro and a TGV line in 1995, there were no significant Islamist attacks until the fire-bombing of the Charlie Hebdo office in November 2011, and the killings of three French soldiers (all of North African origin) and three Jewish children (and one teacher) by Mohamed Merah in Toulouse four months later. These attacks turn out to have been a warning of things to come.

But why was France free of such attacks for over fifteen years, when Madrid and London suffered endless plots and some major atrocities? Given the restrictions placed by successive governments on the foulard (headscarf) and the burka, together with the large French Muslim population (around 10% of the 64 million total), the country would seem to have been fertile ground for fundamentalist anger and terrorist outrages.

One view is that the French authorities were tougher and more effective than, say, the British who allowed Algerian extremists fleeing France after 1995 to find shelter in the Finsbury Park Mosque — to the fury of French officials. Another line is that the French secular model of integration, with no recognition of minorities or enthusiasm for multiculturalism, did actually work. Thus when riots took place in 2005 the alienated youth of the banlieues demanded jobs, fairness, and decent housing — not respect for Islam or Palestinian rights.

A third possible explanation of the long lull before this week’s storm is that French foreign policy had not provoked the kind of anger felt in Spain and Britain by their countries’ roles in the Iraq war, which France, Germany, and some other European states had clearly opposed. Although France had an important role in the allied operations in Afghanistan, its profile was not especially high. Given the slow-changing nature of international reputations the image of France as a friend of Arab states and of the Palestinians endured, while Britain drew hostile attention as the leading ally of the United States in the ‘war against terror’. France, again unlike Britain and the United States, has tended to be pragmatic in negotiations with those who have taken its citizens hostage abroad, facilitating the payment of ransoms and getting them home safely. Its policy was that payments, and the risk of encouraging further captures, were preferable to providing the Islamists with global publicity.

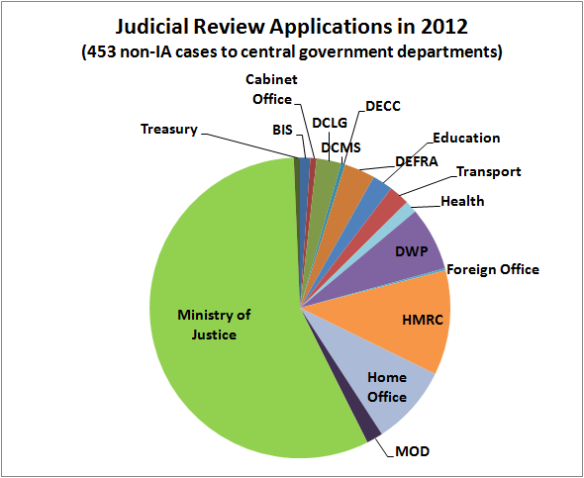

How Many Judicial Review Cases Are Received by UK Government Departments?

During the debate in parliament on Monday 1 Dec 2014, Chris Grayling (Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice) was asked how many Judicial Review cases are brought against government ministers.

Julie Hilling (Bolton West) (Lab): The right hon. Gentleman says “all the time”. Will he give us a notion of how often that is—once a day, once a week, once a month? How many times have such cases happened since April, for instance? He is giving the impression that they happen all the time, but what does that mean?

Chris Grayling: A Minister is confronted by the practical threat of the arrival of a judicial review case virtually every week of the year. It is happening all the time. There are pre-action protocols all the time, and cases are brought regularly. Looking across the majority of a Department’s activities, Ministers face judicial review very regularly indeed. It happens weeks apart rather than months apart.

The minister gave no actual numbers in his answer. So, in this post I’ve looked at how many judicial review (JR) cases were received by central government departments (‘ministers’) over the past few years. This analysis relates to my work with Christopher Hood in the Politics Department at Oxford.

Populism vs. Technocracy? How political parties adapt to new dominant narratives.

Over the last decades, populism and technocracy have attracted a great deal of public attention and generated a lively scholarly debate. As it has recently been argued, they have emerged as the two dominant discourses on the European political scene. As the 2014 European elections clearly showed, even traditional, mainstream political parties increasingly rely on either or both these narratives. One insightful example is the discursive practices of Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party during the Italian electoral campaign.

After his rise as party leader and then Italy’s youngest ever Prime Minister, Renzi has become a favourite of the international press. As early as 2010, when he was still mayor of Florence, the Tuscan politician proved himself an extremely skilled communicator. His idea of ‘rottamare’ (‘scrapping’) the entire political class had an extremely wide impact on public opinion and soon became a slogan for all those who wanted to contest the status quo in Italian politics. The growing support he received from the public convinced him to run for his party’s leadership primaries in 2012 and then, successfully, in 2013. Nowadays, Renzi’s PD embodies an arguably renewed organisation. The internal opposition has been gradually marginalised and the re-compacted majority has developed a political discourse based on pragmatism, hope for the future and the need for change. In particular, one can observe how the PD has gradually assimilated populist and technocratic discursive strategies by examining the ways in which it deals with a key issue such as the European Union.

The populist mode. According to a growing body of literature, typical examples of populist discursive practices include the reliance upon Manichean oppositions, romanticised and essentialist visions of the people, appeals to the multitude whilst excluding others and extreme simplification and moralisation (Wodak 2003).