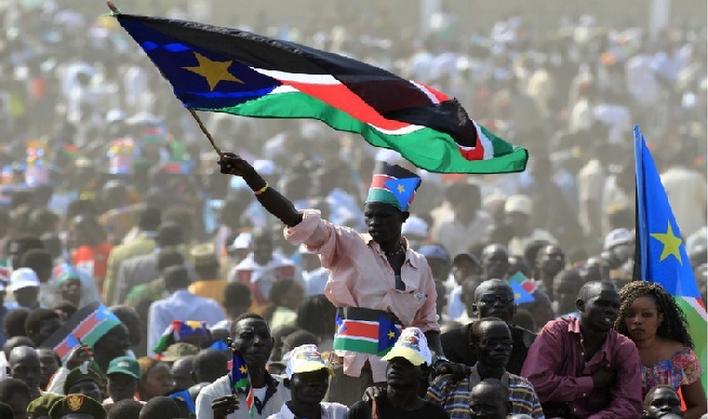

South Sudan: Uganda’s intervention may provoke a regional war

A few days ago, I discussed on Radio France International the collapse of the cease-fire and resumption of open war between the beleaguered South Sudanese government of President Salva Kiir and the rebel forces led by former Vice-President Riek Machar. The violence in South Sudan has since December 2013 claimed the lives of more than 10000 people- a death toll that is rapidly rising as diplomatic efforts have failed to broker a short-term cessation of hostilities, let alone a longer term political solution. The massive intervention of the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF) with thousands of infantrists, tanks and helicopter gunships has, for the time being, saved President Salva Kiir and the Southern Sudanese capital Juba but risks triggering a wider regional crisis that could see Sudanese and Eritrean involvement and would bring back echoes of the devastating regional wars and proxy conflicts of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s during which millions of people perished.

What an El Sissi presidency would mean for Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States

The announcement by Egypt’s Defense Minister, now Field Marshall, Abdel-Fattah El Sissi that he would be running for president was greeted with joy and with apprehension, not only in Egypt, but also in the Gulf States. If current trends hold, it seems increasingly likely that El Sissi will be comfortably elected to serve as president of Egypt for at least the next four years. Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States under a potential El Sissi presidency will largely be shaped by the positions these states have taken in the past few months.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE and Bahrain, who considered the Muslim Brotherhood to be a significant domestic threat, have strengthened relations with Egypt following the overthrow of former president Mohammed Morsi. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, who welcomed Morsi’s overthrow immediately pledged $12 Billion to post-Brotherhood Egypt, increasing their assistance in the subsequent months. If elected, President El Sissi will look to build on the current relationship with these states, possibly by visiting Riyadh, where he previously served as military attaché, and Abu Dhabi soon after the election. Although the UAE’s Prime Minister stated in an interview with the BBC that he “hopes (El Sissi) remains in the military, and that another person [runs] for the presidency”, a clarification was soon issued by the official news agency saying that the “brotherly advice is that General al-Sissi should not run as a military man for the post of the presidency”. El Sissi has already stated that Saudi’s support for Egypt will “never be forgotten” and expressed gratitude for the UAE’s aid.

National Dialogues and Dilemmas: Reflections on Libya and Yemen

The Arab uprisings, initially perceived as one unit of analysis, have gone through a rite of passage and identified themselves as distinct from one another; it is no longer logically sound to talk of one “spring”. Nevertheless, it is instructive to extract lessons learned from each experience and place them into conversation with one another. An Arab dialectic seems possible instead of a unified discourse on change and transitions. Libya’s ‘national dialogue’ has been launched in the hope of carving out a space of peace across the country and for developing a form of consensus on what is perceived as a reborn Libyan nation, post-Qaddafi. The National Dialogue Preparatory Commission’a (NDPC) Chairman Fadeel Lame emphasised that Libya needs to “move from one stage to another and from one situation to another and that this transition could be achieved only through the power of dialogue.”[1] Earlier in September 2013, Tarek Mitri, who heads the UN Support Mission in Libya, described it as a process that “would give voice to many Libyans and opens a space that does not exclude any of those who may have contributions to make to public life and are otherwise isolated, separated or entrenched in their partisan attitudes… [to] promote a national capacity to address urgent priorities and ensure public support to the efforts of state-building.”

The need for dialogue is indisputable in a country that seems ridden with conflict. In Tripoli, separatist movements gaining ground in the eastern part of the country. General instability highlights the urgency for dialogue – and the difficulties. Recently, militias from Misrata opened fire on peaceful protestors in Tripoli who were calling for the departure of militias and the restoration of peace. According to one account, more than 40 were killed and 400 wounded in the clashes.[2] The General National Congress (GNC) and government agencies froze; it was only through the intervention of local councils and civil society that an end of violence was reached.[3] As described by the reporter: “There was a tense calm in Tripoli on Sunday after more than 48 hours of bloodshed. Civil-society and community leaders abided by a general strike that coincided with a national mourning period for those slain. Shops were shut and normally busy commercial streets were devoid of traffic on the first day of the working week, witnesses reported.”

The question here then is not about need – in an ideal world, developing consensus among the Libyan people towards state building and a national identity would be the way out.

It is about capacity.

Yemen’s Eastern Province: The people of Mahra clearly want independence

In late November 2013, I was invited by a cross-tribal delegation in Yemen’s eastern province of Mahra to explain the results of a public opinion survey that I had completed there with their help earlier in the year. Owing to heightened security risks from entrenched interests and al-Qa’ida operatives, around 20 vehicles of trusted tribesmen, armed to the hilt, had made the journey to meet me at the desert crossing between Oman and Yemen. We drove through the night to a fortified compound just outside Mahra’s capital, al-Ghayda. This unfurnished fortress was to be the centre of activity for me and about 50 armed men for the next week. Strangely, I had never slept so well as I did on my roll-up mattress on the floor, safe in the knowledge that three guards remained outside my window all night and a dozen more on the roof above me.

Malala’s Visit to Oxford

Pakistan has always been a divided nation—divided between the forces of progression and regression, between secularists and the rest, between those who believe in social equality and those who don’t. Three days before Pakistan gained independence in 1947, Jinnah, the founding father, made clear that religion would have “nothing to do with the business of the state.” Yet, within a year after his death, the Mullahs prevailed. TheObjectives Resolution, passed by the Constituent Assembly in 1949, laid the basis of an Islamic Republic where religiosity has progressed with every passing decade, culminating in its current violent form.

Resistance to religiosity in the country has also been constant. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the first elected prime minister, attempted liberal socialism in the 70s, but had to succumb to the religious right and was finally hanged by an Islamist general. His daughter, Benazir, struggled for progressive politics since the 80s, until her fateful assassination in 2007.

The alternatives are well known. In their attempt to impose Sharia in the past decade, Taliban extremists have silenced thousands of lives. Yet saner voices continue to emerge to champion national struggle against religious bigotry.

Malala Yousafzai, the survivor of Taliban assassination bid last year, is the latest exponent of this just cause. With the late Benazir as her role model, the 16-year-old girl from a rural town says she wants to become the prime minister of Pakistan.

The cost of Syrian refugees

Recent estimates place the total number of Syrian refugees in Jordan at over 500,000. Zaatari refugee camp has become the fourth largest city in Jordan by population—it may not be much of a home, but each refugee costs the Jordanian government 2,500 dinars ($3,750) to host per year. The cost of Syrian refugees is putting a tremendous strain on the economy and is affecting the patronage systems that have ensured tribal loyalty to Jordan’s monarchy in the past. In addition to increasing resentment within the tribal population, the presence of Syrian refugees has also provided a boost in support for the Muslim Brotherhood, Jordan’s best-organized opposition, thereby adding to the tension the Hashemite Kingdom faces.

Jordan’s ability to absorb Syrian refugees has become a growing issue. Its fiscal position has deteriorated since the beginning of the Arab Spring; hosting 500,000 refugees has already cost Jordan over $800 million since the Syrian war began, and unrest across the Arab world, particularly in neighboring Syria, has cost Jordan’s economy as much as $4 billion. Furthermore, foreign assistance, on which Jordan was able to rely while dealing with the influx of Iraqi refugees, is insufficient. Prime Minister Abdullah Ensour recently stated in an interviewthat “the foreign assistance extended to Jordan is not enough in the face of the extraordinary numbers of Syrian refugees who have sought a safe haven in the Kingdom since the start of the Syrian conflict in March 2011.”

Exit strategies and state building: an interview with Richard Caplan

Professor Richard Caplan, of the DPIR, Oxford, and editor of the new book Exit Strategies and State Building, talks to Politics in Spires about the book itself, the practice of internationally-led state-building and strategies for exit. In this interview, Professor Caplan talks about the practical and normative changes that have taken place in the international arena which this book has responded to and deals with some of the most pertinent issues faced by the international community when attempting to undertake state-building projects.

The legality of military action in Syria: humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect

It now seems fairly clear that the US and the UK are set to take military action in Syria in the coming days in response to the recent chemical attacks there. The UK Prime Minister, UK Foreign Secretary and the UK Secretary of State for Defence have all asserted that any action taken in Syria will be lawful. But on what grounds will military action in Syria be lawful. As is well known, United Nations Charter prohibits the use of force in Art. 2(4), as does customary international law. The UN Charter provides 2 clear exceptions to the prohibition of the use of force: self defence and authorization by the UN Security Council. It is almost certain that there will be no Security Council authorization. In a previous post, I considered the possibility of a (collective) self defence justification for the use of force in response to a use of chemical weapons. The scenario contemplated then is very different from the situation that has emerged, and the language used, at least by the UK, does not hint at a use of force on the basis of national interest. However, President Obama in a CNN interview last week did seem to speak of self defence when he said “there is no doubt that when you start seeing chemical weapons used on a large scale … that starts getting to some core national interests that the United States has, both in terms of us making sure that weapons of mass destruction are not proliferating, as well as needing to protect our allies, our bases in the region.” A justification for force on this basis would sound like preemptive self defence in a way that is very close to the Bush doctrine. I find it hard to see the Obama administration articulating a legal doctrine of preemptive self defence claim in this scenario.