Voter Blues: The European Parliament’s efforts to boost turnout in the 2014 Elections remain problematic

In 2014, 300 million eligible voters across the European Union (EU) will have the opportunity to cast their vote in the elections for the second-largest legislative body in the world: the European Parliament. Currently at 766 members, in the new legislative period, the Parliament will have 751 members who according to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) directly represent the European citizens. And this election is bound to be different—if it is up to Members of European Parliament (MEP) that is. The EP, together with the Commission, is making a huge effort to politicise the process and make the 2014 elections truly European. Although commendable, these efforts are not without problems: in some ways, they stretch the limits of the EU treaties to worrying degrees and risk creating a dysfunctional decision-making context after the elections.

In spite of its considerable (and increasing) powers under the Treaties, the Parliament has since the first election faced decreasing turnouts. In the latest 2009 elections, the average was 43 per cent across the EU-27. Efforts are being made to address this problem. In July 2013, a resolution by MEP Andrew Duff included a wide range of measures to improve turnout, the most important of which is the proposal to have Commission candidates of the EP political groups.

Q&A: China Across the Divide: the domestic and global in politics and society

I recently interviewed Professor Rosemary Foot about her new book, China Across the Divide: the domestic and global in politics and society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), as part of Politics and Spires’s OxOn China series.

NH: What is the book about?

RF: The book’s main argument is that, as students of international relations, we need to do more to collapse the divide between the domestic and global spheres of analysis. I make this argument with special reference to China, but I think it can be applied to other countries. I have chosen three main approaches to illustrate this phenomenon of the interconnectedness between the global and domestic levels of analysis. The first section of the book looks at ideas emerging from within China itself, at both mass and elite levels, about the country’s place in the world and how it should conduct its external relations. The argument is not that these ideas determine policy decisions, but help to shape, or set the broad contours of, the decisions that are arrived at. The second section looks at involvement in inter-societal enmeshments between China and other countries, and both the intended and unintended consequences of these linkages. This part of the book looks at the ways in which these non-state relations are transforming not only China itself but also the world of which it is a part. The third section focuses on three major global issues that are salient or intrusive at the domestic level and which require either some alterations in domestic ways of life or generate resistance at the domestic level to that intrusiveness.

NH: What inspired you to write/edit it?

Munich’s legacy: historical analogy as a tool in marketing foreign policy

U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, made a reference, on two separate occasions, to the Munich Agreement of 1938 as he endeavoured to elicit support for President Barak Obama’s policy in Syria.

During a conference call with Democratic Party members of the House of Representatives on the 2nd of September, Kerry told them that they faced a “Munich moment” as they weighed whether to back President Obama’s call for a limited military strike against Syria.

Speaking in Paris on the 7th of September, during a press conference, Kerry described the situation in Syria as “our Munich moment.”

The Munich Agreement, and the policy of appeasement it represented, is one of the most widely used historical analogies by decision-makers and their advisers in shaping foreign policy, and in selling it to the wider public at home and abroad.

The logic of this comparison runs as follows: a dictator with aggressive intentions has to be stopped, as early as possible, the way the dictators of the 1930s were not. The policy of appeasement that was pursued by Britain and France in the 1930s in order to accommodate those dictators, particularly the German leader, Adolf Hitler, was a failure and millions of people paid with their lives for it.

Following World War II, Munich became a by-word for appeasement, which, in turn, became a by-word for surrender. Just by invoking the term “Munich” both the speaker and his audience knew what was meant by it. Few words in political parlance became so laden with historical connotations as this one did.

The historical roots of Obama’s foreign policy

A common Republican criticism of Barack Obama is that he has been a weak foreign policy president who has little regard for American ideals. Obama ‘has responded with weakness to some of the gravest threats to our national security this country has faced’, charged the 2012 Republican platform. Mitt Romney accused Obama of starting his presidency with ‘an apology tour’. Republican rising star Marco Rubio says Obama wants ‘to make America more like the rest of the world, instead of helping the world become more like America’.

Yet, an examination of the history of US foreign policy and the ideas which influenced it shows that far from being a radical departure from the American norm, Obama’s worldview fits with a historical tradition.

In fact, he sounds much like an early statesman.

Stefan Halper, professor of International Relations at Cambridge and a former adviser to several presidents, argues that US foreign relations have historically been influenced by what he terms ‘Big Ideas.’ Their starting point is the belief in American exceptionalism, the umbrella concept from which all other ideas flow – ranging from the early 19th century Monroe Doctrine to the Bush Doctrine and democracy promotion.

A Reformed Role Model: India is becoming a reluctant promoter of rights

When it comes to human rights, India is a paradoxical case. On the one hand she is praised as a regional standard-bearer, too-often celebrated as ‘the world’s largest democracy’ and applauded for protecting rights when her neighbours do not. On the other hand, the rights community is unanimous in its condemnation of India’s human rights record. Brutal oppression in Kashmir, state mandated ‘encounters’ (unlawful killings) and the violations of tribal land rights are but three of the recurring complaints made of India’s human rights protection record.

The picture is more complicated when it comes to international relations. For many, including Salil Shetty, the Secretary General of Amnesty International, India’s rising power status brings with it a greater responsibility to promote rights internationally. Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia Director of Human Right Watch, said something similar in in a recent high-profile piece: urging India to do more to secure rights globally.

Of course India should do as much as it can to encourage rights protection beyond its borders. But such conclusions fail to explain why India is a reluctant partner in the international effort to protect rights. Perhaps the most instructive question is ‘is it in India’s interests to promote rights globally?’.

When the Party’s Over: The Politics of Fiscal Squeeze in Perspective

Fiscal austerity, fiscal consolidation and spending cutbacks currently dominate the politics of many of the world’s democracies. Old political arguments are being tested with new battles emerging over whose expectations are to be disappointed and who should be blamed for fiscal squeeze. Can the fiscal travails of the early United States in the 1840s, when half of the states then in the Union had to default over their debts and new unpopular taxes had to be imposed in the middle of an international trade slump, help us draw lessons for the Eurozone debt crisis of the early 2010s? Could cases often presented as ‘poster children’ of successful fiscal consolidation (and at those often portrayed as failures or ‘basket cases’) inform us about the politics of those fiscal squeezes? Can governments that copy ‘good’ examples of fiscal squeeze escape punishment at the polls? A recent conference on the politics of fiscal squeeze explored some these issues and looked at how it has played out in different times and places. It considered in depth nine cases of fiscal squeeze (defined as the political effort that goes into reining in expenditure or raising taxes) and explored what conclusions we can draw for current debates about fiscal squeeze from earlier cases in other democracies.

Proposals for decriminalising politics in India

The expert comments as well as gossip about the next general elections is growing louder by the day. Political parties are re-positioning themselves to increase their likelihood of forming the government in 2014. Amidst this hullaballoo, the political class has conveniently turned a deaf ear to the calls by civil society groups to undertake critical electoral reforms such as decriminalising politics.

Several government-appointed Commissions have already made clear recommendations for reforms, but the political will to implement these recommendations in letter and spirit is lacking. At a recent conference on decriminalisation of politics, the Law Minister acknowledged the problem but chose to refer it to yet another Law Commission specially constituted for the purpose. Instead of dilly-dallying, a government that genuinely intends to bring about reform should instead be using its energies to build political consensus to tackle these issues at the earliest. The opposition, too, shares the responsibility for making this happen.

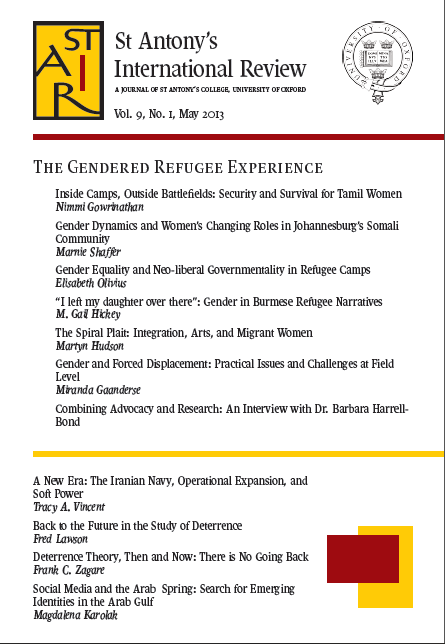

Launch of current issue of the St. Antony’s International Review (STAIR): “The Gendered Refugee Experience”

‘I do not believe that gender equals women—a fact that has been neglected,’ says Dr. Barbara Harrell Bond, in an interview found in the newest publication of the St Antony’s International Review (STAIR), entitled “The Gendered Refugee Experience”. Set to launch on 23 May at 17:00 in Queen Elizabeth House the issue addresses gender as a dimension in claims for asylum and, more centrally, as a central component in post-flight experiences