The Neurochemistry of Power: Implications for Political Change

Power, especially absolute and unchecked power, is intoxicating. Its effects occur at the cellular and neurochemical level. They are manifested behaviourallynin a variety of ways, ranging from heightened cognitive functions to lack of inhibition, poor judgment, extreme narcissism, perverted behaviour, and gruesome cruelty.

The primary neurochemical involved in the reward of power that is known today is dopamine, the same chemical transmitter responsible for producing a sense of pleasure. Power activates the very same reward circuitry in the brain and creates an addictive ‘high’ in much the same way as drug addiction. Like addicts, most people in positions of power will seek to maintain the high they get from power, sometimes at all costs. When withheld, power – like any highly addictive agent – produces cravings at the cellular level that generate strong behavioural opposition to giving it up. In accountable societies, checks and balances exist to avoid the inevitable consequences of power. Yet, in cases where leaders possess absolute and unchecked power, changes in leadership and transitions to more consensus-based rule are unlikely to be smooth. Gradual withdrawal of absolute power is the only way to ensure that someone will be able to accept relinquishing it.

Osborne’s proposed spending cuts after 2015 would be unusual – but not unprecedented

At the beginning of the year, George Osborne announced his intention to push on with spending cuts should the Conservatives be re-elected in 2015. We looked at previous episodes of UK expenditure cutbacks and find that the current proposals are no more extreme. However, the Scottish referendum could mean the stakes in spending-cap politics prove to be higher this time round.

At the beginning of this year the Chancellor, George Osborne, announced a proposal to impose spending cutbacks during the next Parliament. The plan announced was for £25bn of spending cutbacks over the period 2015-17 to deal with the UK’s continuing deficit. That deficit-cutting strategy appeared to rely largely on spending cuts (mostly directed at working-age welfare) and little if at all on tax increases.

The table below compares the outcomes of eight selected episodes of UK spending cutbacks over a 90-year period, including the current coalition government’s spending record based on reported figures up to 2013. It also compares those eight historical episodes with the plans announced by Osborne for further spending cuts before and after the UK general election scheduled for 2015, based on the assumptions (a) that those plans would be fully implemented as announced and (b) that the OBR forecasts of GDP up to 2017 proved to be broadly correct. Both assumptions are of course highly contestable.

The Putin-Khodorkovsky dichotomy: The media got it all wrong

It looked like a scene from a Cold War spy thriller. 24 hours after his release, Oligrach Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who ended a 10-year sentence, appeared in Berlin wearing a heavy duty Russian air-force jacket and smiling broadly. It was, however, the Russian President Vladimir Putin’s announcement about Khodorkovsky’s early release which caught a lot of people by surprise. A global media spectacle followed.Journalists and commentators scrutinised whether Putin’s decision symbolised a political strength or weakness, whether Khodorkovsky admitted his guilt, and whether he is going to become a political opposition figure or remain in exile. Media outlets appeared to be outpacing one another in applying dramatic labels to the momentous event.

A reflection on the media coverage along with the analysis of Khodorkovsky’s interviews of the past few days, however, paints a more ambivalent picture and suggests that the dichotomies and sensational labels applied are often not fitting. The “surprise” label attributed to Putin’s decision, the “disappointment” characterising public reaction at Khodorkovky’s apparent disinterest in re-entering Russian politics, and the “Dissident versus Despot” dichotomy applied to the Putin-Khodorkovky’s relationship, bear closer scrutiny. A closer look at his latest interviews highlights Khodorkovsky’s complex personality and well-formed, but somewhat, contradictory political views.

Scotland: What will happen after the vote

At 650 pages Scotland’s Future is not a light read. It stands as the Scottish Government’s manifesto for a yes vote in the independence referendum. The volume ranges from profoundly important questions relating to currency and Scotland’s membership of the European Union, right down to weather-forecasting and the future of the National Lottery. Though it is likely many copies of Scotland’s Future will be printed, it is unlikely many will be read from cover to cover. Its authors probably do not regret its length: by its very heft, the volume seeks to rebut claims that the consequences of independence have not been carefully thought through. This post considers the immediate constitutional consequences of a yes vote in light of Scotland’s Future. Its central argument will be that the timescale proposed by the Scottish Government for independence following a referendum is unrealistic, and may work against the interests of an independent Scotland.

Q&A with Dr Cristina Parau: Why do politicians let judges have so much power?

Dr Cristina Parau, Department Lecturer in European Politics and Societies at Oxford University, recently edited a special issue of the journal Representation. This issue focuses on the phenomenon of judicial activism in the political sphere. It brings together scholars from different disciplines that hold different perspectives on the judicialisation of politics. It focuses on the contrasts and complementarities of law and politics as modes of democratic representation.

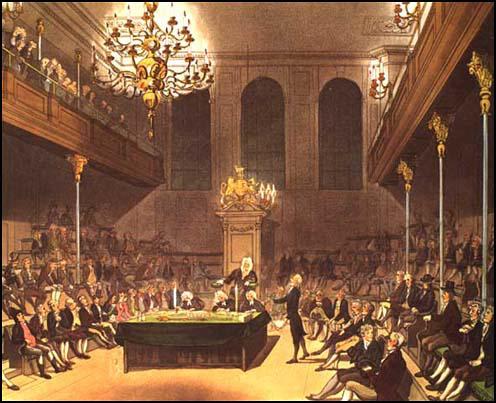

According to Dr Parau, “this special issue seeks to advance our understanding of the judicialisation of politics by bringing together a diverse group of scholars who take different perspectives and apply different methods to investigating the phenomenon and and its impact on representative democracy. The transfer of policy-making power from popularly elected representatives to a judicial elite would seem to weaken democracy in a quite straightforward, zero-sum way, contributing to Europe’s already destabilising democratic deficit. On this account, a renewal of parliamentarism is the only effectual and legitimate cure. On the other hand, ‘representative democracy’ has been criticised since the eighteenth century as elite rather than popular rule; Aristotle classified it as ‘oligarchy’. Representation has defects that might be remedied by judicial intervention. Some scholars have suggested that judicialisation provides a venue for the more active participation of citizens marginalised by the failures of representation; while others even see in judges a form of representativeness with unique properties. The articles in this Special Issue probe these accounts.”

I recently asked her a few questions about the project.

Merkel’s Grand Coalition: A new chance for Germany’s social democracy

Fears over a grand coalition are again haunting Germany’s social democracy. As was the case in 2005, the new coalition is comprised of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, together with the CSU, its Bavarian pendant) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Such a composition worries many Social Democrats given the last experience with a coalition in 2009 when the SPD vote share shrank by 12.2 per cent. Some Social Democrats are even doubtful about whether the SPD can survive another grand coalition with Angela Merkel’s CDU.

While the pessimism is understandable, it is misplaced. Another grand coalition will not necessarily produce negative consequences for Germany’s Social Democracy, for three reasons.

First and most importantly, there is no clear pattern whereby the smaller coalition partner loses in a grand coalition. The two previous grand coalitions at the national level offer mixed examples. While the last experience was surely painful for the SPD, it actually benefited from the first grand coalition from 1966 to 1969. Despite some unpopular decisions in the Social Democratic camp at the time, such as the emergency laws (Notstandsgesetze), the SPD received part of the credit from its association with several governmental accomplishments, most notably the economic policies that led to the end of Germany’s first economic recession after World War II. At the time, the SPD had managed to find the right balance between its own political autonomy and participation in the grand coalition, acquiring a reputation for pragmatism and responsibility. This was most embodied by Karl Schiller, the minister of the economy, Herbert Wehner, the party chairman, and Helmut Schmidt, the leader of the SPD’s parliamentary group. Despite being the junior partner in a grand coalition, the SPD thus succeeded in proving its worth. This, in turn, helped the Social Democrats take over as the majority party in 1969, putting an end to 20 years of Christian Democratic dominance.

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Play Episode

Pause Episode

Mute/Unmute Episode

Rewind 10 Seconds

1x

Fast Forward 30 seconds

00:00

/

Subscribe

Share

RSS Feed

Share

Link

Embed

Download file | Play in new windowIn years to come, Saturday 30 November 2013 may be remembered as the last time that a genuinely united Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland came together to celebrate St Andrew’s Day (Scotland’s official national day). With a referendum on Scottish independence set to take place in Scotland on 18 September 2014, the British state’s survival is far from certain. A majority vote in favour of independence would not result in the immediate break-up of the UK (though the Scottish National Party have recently called for full Scottish separation by March 2016 if independence is endorsed at the ballot box). But even so, it is clear that victory for the independence campaign would leave British national unity – terminally battered and bruised – as little more than a wishful façade. If the Great British edifice crumbles to the ground, what are we to make of the pieces that remain?

Identifying the Barriers to Gun Control: lessons from Virginia

For outside observers, gun control seems to be an oxymoron in America. Even following the school shooting in Newtown, the Senate failed to pass an amendment mandating universal background checks on sales of firearms. President Obama reacted with visible anger. He had staked much of his post-election political capital on ‘gun sense’, only to have a watered-down bipartisan bill proposed by two pro-gun Senators muster just 54 votes in the Senate. Polling revealed that the bill had more than 80% support amongst Democrats, Republicans and independent Americans.

The formal American system is famously anti-majoritarian: it is a cluster of staggered, disjointed and (in the case of the Supreme Court) even mythical legitimacies, all of which exercise influence over federal legislation. But questions remain as to why America cannot pass stricter gun laws, when a majority of Americans support a number of increased restrictions.