The insecurity of a security state: What can Hannah Arendt tell us about Egypt?

In Egypt, it is clear that constructive results are not going to materialise anytime soon. Increasing state violence, arrests and intimidation have no clear logic beyond an attempt by the security apparatus to regain power and tighten control over the economy. It is an outworn order that risks collapsing.

While the regime does have a serious security issue on its hands, namely the Sinai-based terrorism that has now spread to Cairo, the regime is increasingly blurring the lines between terrorism and anyone who opposes the official line. Labelling the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, outlawing anti-regime protests, cracking down on NGOs and the clampdown against anti-regime activists and journalists are indications that the security state is disintegrating. The regime is carrying out violent measures against Islamists and youth – two major groups that cannot afford to be alienated – signalling the regime’s struggles to control a significant segment of the population via peaceful means.

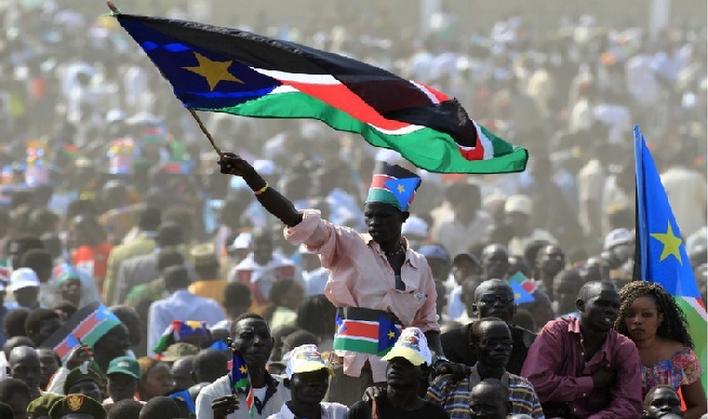

South Sudan: Uganda’s intervention may provoke a regional war

A few days ago, I discussed on Radio France International the collapse of the cease-fire and resumption of open war between the beleaguered South Sudanese government of President Salva Kiir and the rebel forces led by former Vice-President Riek Machar. The violence in South Sudan has since December 2013 claimed the lives of more than 10000 people- a death toll that is rapidly rising as diplomatic efforts have failed to broker a short-term cessation of hostilities, let alone a longer term political solution. The massive intervention of the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF) with thousands of infantrists, tanks and helicopter gunships has, for the time being, saved President Salva Kiir and the Southern Sudanese capital Juba but risks triggering a wider regional crisis that could see Sudanese and Eritrean involvement and would bring back echoes of the devastating regional wars and proxy conflicts of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s during which millions of people perished.

What an El Sissi presidency would mean for Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States

The announcement by Egypt’s Defense Minister, now Field Marshall, Abdel-Fattah El Sissi that he would be running for president was greeted with joy and with apprehension, not only in Egypt, but also in the Gulf States. If current trends hold, it seems increasingly likely that El Sissi will be comfortably elected to serve as president of Egypt for at least the next four years. Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States under a potential El Sissi presidency will largely be shaped by the positions these states have taken in the past few months.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE and Bahrain, who considered the Muslim Brotherhood to be a significant domestic threat, have strengthened relations with Egypt following the overthrow of former president Mohammed Morsi. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, who welcomed Morsi’s overthrow immediately pledged $12 Billion to post-Brotherhood Egypt, increasing their assistance in the subsequent months. If elected, President El Sissi will look to build on the current relationship with these states, possibly by visiting Riyadh, where he previously served as military attaché, and Abu Dhabi soon after the election. Although the UAE’s Prime Minister stated in an interview with the BBC that he “hopes (El Sissi) remains in the military, and that another person [runs] for the presidency”, a clarification was soon issued by the official news agency saying that the “brotherly advice is that General al-Sissi should not run as a military man for the post of the presidency”. El Sissi has already stated that Saudi’s support for Egypt will “never be forgotten” and expressed gratitude for the UAE’s aid.

What is the future for the ‘China governance model’?

The leadership turnover in China last year took place in a shifting political situation. Namely, there have been increased calls for more political accountability and multi-candidate elections, broader media freedom and financial reform.

We need to watch this closely. How China’s leadership reacts to these calls for change will determine whether it will continue its phenomenal ‘rise’ or be hampered by intransigence.

Let’s take a closer look at the context. The uprisings in the Arab world have prompted many to ask whether China will be the next to be swept along in a wave of popular unrest that has toppled rulers in several countries. Indeed, the Chinese leadership, both in power and previously in power, has been watching the situation carefully. This attention has been particularly justified considering that the current Chinese president assumed power at a time when social media became a real force. These new forms of communication played an undisputable role in the Arab and Maghreb uprisings. Now, half a billion Chinese are registered on Sina Weibo, a website much like Twitter. This online platform has served “netizens” to voice many complaints ranging from governance malfunctions and corruption to food and environmental issues.

This raises inevitable questions. Is the bid for democratic reform a matter of time? Might the prediction of an “end of history” and of a uniform move in the direction of liberal democracy make a comeback? Or, might there be other sustainable alternatives?

National Dialogues and Dilemmas: Reflections on Libya and Yemen

The Arab uprisings, initially perceived as one unit of analysis, have gone through a rite of passage and identified themselves as distinct from one another; it is no longer logically sound to talk of one “spring”. Nevertheless, it is instructive to extract lessons learned from each experience and place them into conversation with one another. An Arab dialectic seems possible instead of a unified discourse on change and transitions. Libya’s ‘national dialogue’ has been launched in the hope of carving out a space of peace across the country and for developing a form of consensus on what is perceived as a reborn Libyan nation, post-Qaddafi. The National Dialogue Preparatory Commission’a (NDPC) Chairman Fadeel Lame emphasised that Libya needs to “move from one stage to another and from one situation to another and that this transition could be achieved only through the power of dialogue.”[1] Earlier in September 2013, Tarek Mitri, who heads the UN Support Mission in Libya, described it as a process that “would give voice to many Libyans and opens a space that does not exclude any of those who may have contributions to make to public life and are otherwise isolated, separated or entrenched in their partisan attitudes… [to] promote a national capacity to address urgent priorities and ensure public support to the efforts of state-building.”

The need for dialogue is indisputable in a country that seems ridden with conflict. In Tripoli, separatist movements gaining ground in the eastern part of the country. General instability highlights the urgency for dialogue – and the difficulties. Recently, militias from Misrata opened fire on peaceful protestors in Tripoli who were calling for the departure of militias and the restoration of peace. According to one account, more than 40 were killed and 400 wounded in the clashes.[2] The General National Congress (GNC) and government agencies froze; it was only through the intervention of local councils and civil society that an end of violence was reached.[3] As described by the reporter: “There was a tense calm in Tripoli on Sunday after more than 48 hours of bloodshed. Civil-society and community leaders abided by a general strike that coincided with a national mourning period for those slain. Shops were shut and normally busy commercial streets were devoid of traffic on the first day of the working week, witnesses reported.”

The question here then is not about need – in an ideal world, developing consensus among the Libyan people towards state building and a national identity would be the way out.

It is about capacity.

Yemen’s Eastern Province: The people of Mahra clearly want independence

In late November 2013, I was invited by a cross-tribal delegation in Yemen’s eastern province of Mahra to explain the results of a public opinion survey that I had completed there with their help earlier in the year. Owing to heightened security risks from entrenched interests and al-Qa’ida operatives, around 20 vehicles of trusted tribesmen, armed to the hilt, had made the journey to meet me at the desert crossing between Oman and Yemen. We drove through the night to a fortified compound just outside Mahra’s capital, al-Ghayda. This unfurnished fortress was to be the centre of activity for me and about 50 armed men for the next week. Strangely, I had never slept so well as I did on my roll-up mattress on the floor, safe in the knowledge that three guards remained outside my window all night and a dozen more on the roof above me.

Malala’s Visit to Oxford

Pakistan has always been a divided nation—divided between the forces of progression and regression, between secularists and the rest, between those who believe in social equality and those who don’t. Three days before Pakistan gained independence in 1947, Jinnah, the founding father, made clear that religion would have “nothing to do with the business of the state.” Yet, within a year after his death, the Mullahs prevailed. TheObjectives Resolution, passed by the Constituent Assembly in 1949, laid the basis of an Islamic Republic where religiosity has progressed with every passing decade, culminating in its current violent form.

Resistance to religiosity in the country has also been constant. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the first elected prime minister, attempted liberal socialism in the 70s, but had to succumb to the religious right and was finally hanged by an Islamist general. His daughter, Benazir, struggled for progressive politics since the 80s, until her fateful assassination in 2007.

The alternatives are well known. In their attempt to impose Sharia in the past decade, Taliban extremists have silenced thousands of lives. Yet saner voices continue to emerge to champion national struggle against religious bigotry.

Malala Yousafzai, the survivor of Taliban assassination bid last year, is the latest exponent of this just cause. With the late Benazir as her role model, the 16-year-old girl from a rural town says she wants to become the prime minister of Pakistan.

The End of the Arab Spring

In December 2010, a revolutionary spark in Tunisia initiated what is now referred to as the Arab Spring. Since then, many countries across the broader Middle East have been swept up in uprisings that have led to fundamental shifts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. The same drive for change has also led to minor changes in Jordan, Morocco, and elsewhere.

These events have drawn the attention of many regional and international observers, experts, and scholars. In many circles, there was a widespread optimism with respect to the nature and course of the Arab Spring, and some observers held to the domino theory, that is, if one revolution took hold, others would follow. Indeed, these expectations and interpretations have been proven true to some degree. First, the contemporary Arab uprisings were able to put an end to dictators and quasi-dictators in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, such that the deposed presidents and parts of their cliques were arrested (e.g., Egypt), accused of state crimes and corruption (e.g., Tunisia), or caught and murdered (Libya). Second, these events put these countries on a path toward political transformation. In this way, we have seen in the major Spring-nations the establishment of new political parties and elections. Due to the modification of whole regimes, these states have completed successful transitions; a significant first step toward democratization.