Cloaks of Invisibility: The latest frontier in military technology

Fiction and reality have meshed to incredible extents in the past decades, and it is no longer a surprise to see sci-fi-inspired inventions used in everyday life. The military field has been no exception and is now at the cusp of groundbreaking innovations that could change war-making to its core.

The next frontier in defense technology is so-called “stealth” technologies, in which the U.S. military has already invested huge funds. New research is opening up the prospect of achieving something close to invisibility on the battlefield, a breakthrough likened to Harry Potter`s famous invisibility cloak. While most stealth technologies are designated to elude enemy radars, new invisibility technologies could conceal objects in real time, not just from radar but from the naked eye.

The science of invisibility took off in the mid 2000s. This research has mostly involved the use of metamaterials, which are extremely thin composites that bend electromagnetic waves in a way that negatively refracts lights. Cloaking mechanisms use metamaterials to route light waves around an object and create the sensation of looking through the object.

The insecurity of a security state: What can Hannah Arendt tell us about Egypt?

In Egypt, it is clear that constructive results are not going to materialise anytime soon. Increasing state violence, arrests and intimidation have no clear logic beyond an attempt by the security apparatus to regain power and tighten control over the economy. It is an outworn order that risks collapsing.

While the regime does have a serious security issue on its hands, namely the Sinai-based terrorism that has now spread to Cairo, the regime is increasingly blurring the lines between terrorism and anyone who opposes the official line. Labelling the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, outlawing anti-regime protests, cracking down on NGOs and the clampdown against anti-regime activists and journalists are indications that the security state is disintegrating. The regime is carrying out violent measures against Islamists and youth – two major groups that cannot afford to be alienated – signalling the regime’s struggles to control a significant segment of the population via peaceful means.

What an El Sissi presidency would mean for Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States

The announcement by Egypt’s Defense Minister, now Field Marshall, Abdel-Fattah El Sissi that he would be running for president was greeted with joy and with apprehension, not only in Egypt, but also in the Gulf States. If current trends hold, it seems increasingly likely that El Sissi will be comfortably elected to serve as president of Egypt for at least the next four years. Egypt’s relations with the Gulf States under a potential El Sissi presidency will largely be shaped by the positions these states have taken in the past few months.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE and Bahrain, who considered the Muslim Brotherhood to be a significant domestic threat, have strengthened relations with Egypt following the overthrow of former president Mohammed Morsi. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, who welcomed Morsi’s overthrow immediately pledged $12 Billion to post-Brotherhood Egypt, increasing their assistance in the subsequent months. If elected, President El Sissi will look to build on the current relationship with these states, possibly by visiting Riyadh, where he previously served as military attaché, and Abu Dhabi soon after the election. Although the UAE’s Prime Minister stated in an interview with the BBC that he “hopes (El Sissi) remains in the military, and that another person [runs] for the presidency”, a clarification was soon issued by the official news agency saying that the “brotherly advice is that General al-Sissi should not run as a military man for the post of the presidency”. El Sissi has already stated that Saudi’s support for Egypt will “never be forgotten” and expressed gratitude for the UAE’s aid.

Malala’s Visit to Oxford

Pakistan has always been a divided nation—divided between the forces of progression and regression, between secularists and the rest, between those who believe in social equality and those who don’t. Three days before Pakistan gained independence in 1947, Jinnah, the founding father, made clear that religion would have “nothing to do with the business of the state.” Yet, within a year after his death, the Mullahs prevailed. TheObjectives Resolution, passed by the Constituent Assembly in 1949, laid the basis of an Islamic Republic where religiosity has progressed with every passing decade, culminating in its current violent form.

Resistance to religiosity in the country has also been constant. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the first elected prime minister, attempted liberal socialism in the 70s, but had to succumb to the religious right and was finally hanged by an Islamist general. His daughter, Benazir, struggled for progressive politics since the 80s, until her fateful assassination in 2007.

The alternatives are well known. In their attempt to impose Sharia in the past decade, Taliban extremists have silenced thousands of lives. Yet saner voices continue to emerge to champion national struggle against religious bigotry.

Malala Yousafzai, the survivor of Taliban assassination bid last year, is the latest exponent of this just cause. With the late Benazir as her role model, the 16-year-old girl from a rural town says she wants to become the prime minister of Pakistan.

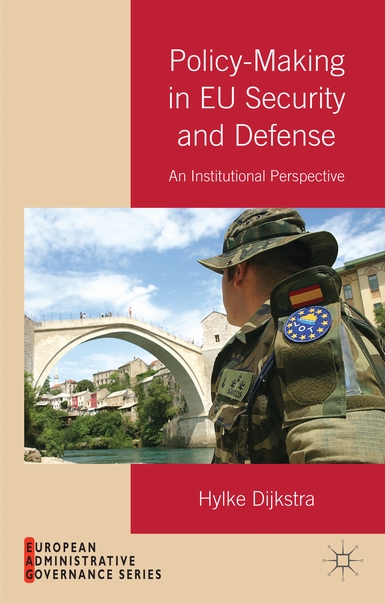

Policy making in EU Security and Defense: A Q&A with Hylke Dijkstra

Hylke Dijkstra, a Marie Curie fellow here in Oxford, has brought out a book that is of considerable contemporary interest as the EU struggles to relocate itself more firmly in the world not only of economics and finance, but of international relations. Congratulations to him!

Security has been a catch-phrase for our times. Military, civilian, human, legal, economic, environmental? Delivered by states, institutions, by NGOs, by citizens, by armies or judges? The term has been defined almost to ‘meaningless-ness’. Classical defence debates have virtually disappeared from our vocabularies. And no roomful of political scientists could ever agree on an exhaustive list of what the most important security and defence threats actually are. So Dijkstra’s book is an ambitious one.

Why the enormous interest in the mothballed Euro Hawk drone deal?

In a recent Politics In Spires post, Tina Schivatcheva discusses the scandal surrounding ‘Euro Hawk’, the failed US-German drone programme. In the post, Ms Schivatcheva asserts that the German public was ‘keep[t] […] in the dark for 13 consecutive years’ regarding the surveillance drone project.

But this is incorrect. Plans for the project were officially announced at the Paris Air Show, Le Bourget, in 2001. At the Berlin Air Show ILA in 2002, the interested public could admire a full-scale mock-up of the Euro Hawk/Global Hawk, and the specialised press has reported on the deal since the early 2000s.

The general press, however, took little notice of the programme. Only when the plans began to generate costs – as for instance in 2009 when the Bundestag’s budget committee was asked to give the deal its blessing – some media outlets reported on the issue.

Therefore, Ms Schivatcheva is probably correct in that most German citizens only heard about the programme to equip Northrop Grumman’s Global Hawk airframe with German surveillance technology – thereby creating the Euro Hawk – when the project was scrapped in May 2013. When the cancellation of the project was made public, however, emotions began to run high. Many speculated whether the failed deal might lead to the resignation of German Defence Minister Thomas de Maizière, which the political opposition demanded outright. Mr Maizière was only saved by the upcoming federal elections: in the run-up, Chancellor Merkel could not afford to lose one of her most valuable ministers.

In my view, the surprising aspect of this scandal is not that the German public seemed to have known little about the deal before its untimely end. What is surprising is the enormous public interest created by the failed deal. For months after the project’s cancellation, debates of the matter did not abate and the enquiry commission asked to look into the matter received wide media coverage.

How to respond to the Nairobi terrorist attacks

Following the terrorist attack on the Westgate Mall in Kenya, there have been calls for the government to pursue a number of different strategies which, if they are implemented on their own, they are likely to fail.

An integrated approach is the only way to secure Kenya. But even this will have little effect unless it goes hand in hand with a serious attempt to reform the military and the police.

In the wake of the German elections – the all-too-soon forgotten Euro Hawk drone scandal

Was it not Germany’s choice and commitment to be a civilian power? The German federal elections have run their course and the CDU/CSU gained the lion’s share of the public’s support. Apparently the electoral results were unaffected by the major political scandal of the summer – the spectacular failure of the Euro Hawk surveillance drone programme. The program has been in the making for 13 years during three consecutive government mandates – in two of these mandates the CDU/CSU has been the major political power. The ‘rise and fall’ of the surveillance drone has also come at a cost of half a billion euros to the German taxpayers. Should such a scandal be forgotten so quickly?

‘Drones’ evoke recent American military campaigns, rather than the dusty Ministerial offices in the German capital. Thus, in the summer of 2013, the news of the ‘rise and fall’ of a German surveillance drone caught the German and European public by surprise. As the long silence of the German government on the acquisition of this new military capability was suddenly broken, the public learnt with astonishment that for 13 years the programme has been lurching on, even though the surveillance drone’s flying problems have long been ‘ a fact universally acknowledged.’ Years have gone by, but the technological problems have remained unresolved and the aviation authorities would not certify the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) due to its lack of an anti-collision system. In 2013, Germany finally bid an official farewell to the Euro Hawk. Amidst the noise of the heated televised debates and the tearful (for some) farewell to this particular weapon, the old message that once Hemingway made about the hopelessness and futility of war was all but muted.