Post-Brexit wave of hate has laid bare the tensions and divisions in Britain

Following the vote to leave the European Union, there has been a sudden upsurge in racist incidents in Britain. The wave of hate has taken many people by surprise, and has laid bare some of the tensions and divisions eating away at the heart of the United Kingdom. It has also called into question Britain’s claim to be a liberal and inclusive multicultural society, leading to considerable soul searching. A state that has often spoken out against identity politics and prejudice abroad is now facing up to the reality that these issues need to be addressed back home. Predictably and understandably, much of the recent commentary as focussed on the divisive referendum campaign and the fact that the UK voted …

Greece has become the EU’s third protectorate

The EU looks, walks and talks like an empire. After extending its borders into Central and Eastern Europe, the EU has just created its third protectorate in the Balkans. From now on Greece will effectively be run by the EU the way Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina already are. Empire is not a synonym of evil despite some bad historical connotations, especially from the colonial era. Power can be exercised in noble ways, and peripheries often prefer to be “conquered” than abandoned. However, the EU’s ambition to run dysfunctional countries by decree is doomed to fail and will represent yet another blow to the project of European integration. Formal involvement of the UN or the IMF in running the protectorates will not …

Dear Prime Minister – it’s time to do much, much more to help Europe’s refugees

In a letter published in The New Statesman, a number of Oxford academics argue that the current government position is bad policy, bad politics and a betrayal of a proud British tradition. Dear Prime Minister and Home Secretary, We the undersigned are dedicated to creating a socially just world. We spend our working lives supporting and promoting research, initiatives, and projects which will create a fairer and more equitable society for everyone. Among our number are many leading experts on community cohesion, asylum, refugees, migration, politics, public opinion, policy and law. We believe the Government’s current position on the European refugee crisis is misguided and requires urgent change. Britain has a long and proud tradition of providing sanctuary to those in …

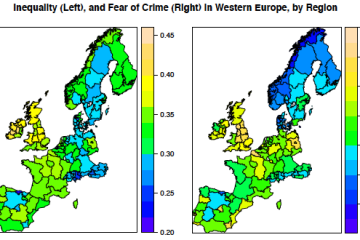

The externalities of inequality: fear of crime and preferences for redistribution in Western Europe

The forthcoming article in the American Journal of Political Science “The Externalities of Inequality: Fear of Crime and Preferences for Redistribution in Western Europe” by David Rueda and Daniel Stegmueller is summarized by the authors here: Many politicians would agree that an individual’s relative income (i.e., whether she is rich or poor) affects her political behavior. Income differentials and the increase in inequality experienced in the recent past have become an important part of electoral politics in most industrialized democracies. If income matters to individual political behavior, it seems reasonable to assume that it does so through its influence on individual preferences for redistribution. The relationship between income inequality and redistribution preferences, however, is a hotly contested topic in the comparative political economy literature …

The fatalistic predicament of Ukraine

Bloody clashes in front of the Ukrainian Parliament have reminded us about the EU’s tormented neighbour. Ultra-nationalists were not successful in the last parliamentary elections, but the tragic situation in Donbas has allowed them thrive. At stake this time were planned changes to the Ukrainian Constitution that envisaged a territorial decentralization as stipulated by the Minsk Agreement. For Ukrainian radicals these changes “imposed” from outside amount to a partition of their country. Is Ukraine unravelling? I do not think so, but much depends on Europe. European leaders said many times that the future of Europe and Ukraine are entangled. The last thing they want is to have a huge failed state on their eastern border. This is why President Poroshenko …

Exit, voice, and loyalty in Europe

Complex situations often require us to take a step back for what consultants call the 10,000 feet view. The problems facing the EU these days—from Grexit to Brexit—surely seem impenetrable. A convoluted potpourri of economic, financial, and political crises leaves most observers either completely disengaged or increasingly reliant on their gut feelings. To wrap one’s head around the forces that threaten the European project, it helps to think in very simple categories: exit, voice, and loyalty. Few theories still prompt real-life insights almost half a century after their publication. Albert O. Hirschman’s “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty” surely falls into this category. Put simply, Hirschman postulated that members who are unsatisfied with an organisation they are part of, can either exit …

The saddest Greek tragedy of all

Ending what has been a tumultuous six-month long negotiation process, last week the Greek Parliament approved the first package of austerity measures required by Greece’s creditors as part of the “Greekment” reached in the early morning hours of 13 July 2015 in order to initiate talks on a Third Fiscal Adjustment Programme (or “Memorandum”) and avoid Greece’s expulsion from the Eurozone. According to early reports, this Memorandum cover the Greece’s financing needs for the next three years, but will require the harshest set of austerity measures of the three fiscal adjustment programmes to date. In this first package alone, the Greek government is obliged to implement tax increases and pension cuts totalling approximately 2% of GDP, while future austerity measures …

Rebuilding democracy in Iceland: an interview with Birgitta Jonsdottir

In the first of a series of interviews by Phil England examining the situation in Iceland and the possible relevance of developments there to the UK, Phil talks to Pirate Party MP Birgitta Jonsdottir. Birgitta Jonsdottir is a co-founder of the Icelandic Pirate Party and one of three Pirate Party MPs in the Icelandic government. Since March the Pirates have been polling as the most popular party in Iceland. Their core policies focus on direct democracy, civil rights and access to information. A former Wikileaks volunteer, Jonsdottir describes herself as an anarchist and a poetician. She is also founder and Chair of the International Modern Media Inititative (IMMI) which aims to strengthen democracy through transparency of information. Could the right to information clauses …