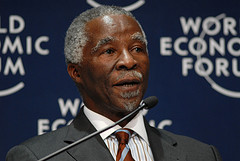

The institutions of the United Nations are slaves to the objectives of Western powers, and these powers are determined to make Africa an appendage to the West. Or so Thabo Mbeki claims. Mbeki, the former president of South Africa and the founding chairperson of the African Union, made these comments in a recent speech deploring what he termed the ‘re-colonisation’ of Africa. Mbeki went on to suggest that recent armed interventions in Africa were representative of the West’s willingness to exploit the universal principles of democracy, human rights and good governance to further their material interests.

Re-colonisation is an idea that by now suffers from severe intellectual fatigue. The harshness of Mbeki’s terms of reference is reminiscent of the ramblings of one Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe. It is difficult to forget Mugabe’s reference to Tony Blair as ‘Bliar’ and his continued insistence that the then Prime Minister be arrested for crimes against humanity. Mbeki, however, is no fool. The continent itself was not spared a severe tongue-lashing from the Sussex-educated man, whose speeches are interspersed with quotes from Yeats, Keats and WEB DuBois. Mbeki criticised Africa’s disunity and weakness in preventing such re-colonisation.

Indeed, Mbeki is no Mugabe. It would be all too easy to dismiss his utterances as those by a typical African strongman determined to lash out at those who stole from Africa. But this would be something of an injustice. However tired notions of re-colonisation and unwanted Western interference may be, at least three events over the past year mean that Mbeki’s position is deserving of closer inspection.

The resolution of the presidential crisis in the Ivory Coast is the first instance. Members of the African Union wanted one thing — a mediated resolution — while Western powers wanted another. They were hoping Laurent Gbagbo would admit defeat and step aside for Alassane Ouattara. But there was little sympathy outside of Africa for the AU’s position and ultimately Gbagbo was arrested by French servicemen (France being the former colonial power of that country).

Fast forward to the crisis in Libya, and the result is almost identical. The African Union wanted one thing; Western powers wanted another. In the end, NATO got what they wanted and the AU considered largely irrelevant.

Abdoulaye Wade, President of Senegal, and his bid to run for a third term in office is the root of a third flashpoint. Regardless of what Western powers say, this is yet another example of Western wishes clashing with those of Africans.

But are clashing perspectives on how to resolve these issues enough to label the West as ‘re-colonialists’? Is intervention in a country an act of colonisation simply because the intervening country has something to gain? Should African leaders make more of an effort to delineate Western interests from those of African states?

The answers are complicated. There is certainly a naivety amongst many in the West as to the extent to which African leaders believe that they are in danger of re-colonisation. It is a genuine fear that guides policy, and is not simply a means for one autocratic leader to justify protecting another. But there is an equal naivety amongst African leaders. Yes, colonisation was a form of intervention for the purpose of explicit material gains. Yes, in most cases, Western powers will only intervene in an African country if there is some explicit advantage for them. But that does not mean that contemporary intervention is a form of colonisation.

It has been said many times, and is worth saying yet again: African leaders need to break free of colonial thinking. Colonialism was an extreme where foreign powers crudely removed any sense of self-determination from local inhabitants, and did not allow African states any sense of sovereignty. Nowadays things are slightly different. It is right to claim that actions are now being taken that are both in the interests of Western powers and that undermine the sovereignty of African states; but to frame them in ‘colonial’ terms is inflammatory and risks becoming associated with statements from less well-meaning leaders. Mbeki, one of Africa’s leading intellectuals, should know better.

Seamus Duggan is a MPhil student in International Relations at Oxford.

4 Comments

[Editor’s note: we have removed certain sentences from this post on the grounds that it was a personal attack. Please treat all posters with respect and refer to TOCs]

We disagree with the author’s position. [Amended by editor] “Colonialism was an extreme where foreign powers crudely removed any sense of self-determination from local inhabitants, and did not allow African states any sense of sovereignty.” He would like to conclude, “Nowadays things are slightly different.” It is precisely because of this “slight” difference that we use the term “neo-colonialism”. Indeed, Kwame Nkrumah defined neo-colonialism in even broader terms:

“Faced with the militant peoples of the ex-colonial territories in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, imperialism simply switches tactics. Without a qualm it dispenses with its flags, and even with certain of its more hated expatriate officials. This means, so it claims, that it is ‘giving’ independence to its former subjects, to be followed by ‘aid’ for their development. Under cover of such phrases, however, it devises innumerable ways to accomplish objectives formerly achieved by naked colonialism. It is this sum total of these modern attempts to perpetuate colonialism while at the same time talking about ‘freedom’, which has come to be known as neo-colonialism.” [See: Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of imperialism by Kwame Nkrumah http://bit.ly/i6AnzR%5D

[The author] struggles to come to terms with the barbarity and naked selfishness of both the colonial and the neo-colonial era. The narratives on both what really happened in the Ivory Coast and Libya are helpless dependent on the uncritical reporting of the corporate media with a vested interest in the outcomes of these conflicts. Most of them practically engaged more in psychological warfare than news reporting.

[Editor’s note: we removed a line here that we felt was a personal attack] Any examination of the actual facts demonstrates it is not possible to determine by vote count who actually won the election in Cote d’Ivoire. The process and the ballots were too compromised. France and the US arranged to have their favorite announced the winner. They endlessly repeated the phrase “internationally recognized’ to successfully spin the narrative that Ouattara won. One man, who was not from Ivory Coast, decided the Ivoirian election. U.N. mission chief to Ivory Coast Y.J. Choi announced, without reference to poll observers, ballot counts, or the Ivoirian constitution, that Ouattara won.

In the case of Libya, that was just flat out naked aggression. A “no-fly zone” was turned into a massive attack on Libyan citizens and infrastructure. A successfully independent and secular state may have been reduced to the chaos of Somalia. That has not finished playing out, and will not for decades. Africans in Libya from other countries were and continue to be subjected to mayhem and murder. The US will probably get a large military base in Libya, where it used to have one before Gaddafi. It will then proceed with its plans to wage proxy war and cause chaos on the continent. Libya’s oil and water will go to serve western bankers.

We seriously invite the writer to our website [rest of sentence removed]. We would in particular, like to refer him to: 1. Libya, Total Victory In Libya, “The Jewel In The Crown” Is Libyan Oil http://bit.ly/yluOlh, and 2. Ivory Coast: Cote d’Ivoire: A “Chocolate Revolution” Or War For Oil? http://bit.ly/ho0L7U.

As Patrice Lumumba wrote:

“History will one day have its say, but it will not be the history that Brussels, Paris, Washington, or the United Nations will teach, but that which they will teach in the countries emancipated from colonialism and its puppets… a history of glory and dignity.”

— Patrice Lumumba, October 1960

For Life, the Environment, and Social Justice!

Social Media Outreach

Pan-Africanist International – a grammar of Pan-Africanism and its manners of articulation.

E-mail: SocialMedia@panafricanistinternational.org

Website: http://www.panafricanistinternational.org/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/#!/PanAfricanists

Barbarity and exploitation are not the sole property of colonialists or Westerners sir. The attitude of conflict that is manifested today between American interests and African interests is the same attitude that has defined humankind for all its history.

In Rwanda the Hutus committed mass killing against their countrymen the Tutsis. In countless African countries have Dictators and Military coups claimed lives of as you correctly say, innocent Africans. But the race or status of these deceased as Africans in no way entitles them to exaggerated sympathy. War and death is the trademark of human interaction, you need look no further than the European Wars of the early to mid 20th century for proof of that.

War in the traditional sense and the more subtle, economically linked conflicts of the modern era are human problems, not African problems. America will always act in its best interests as any country will and the fact that they are more powerful than African countries and that any power struggle will automatically be skewed in their favour is natural albeit unfortunate.

Neo-colonialism as you call it is a symptom of an on-going dominance of a certain economic mindset that was developed by those powers who hold the global chips and have done so for some time. The fact that it benefits some and not others goes without saying and the same would apply to ANY economic theory. So your issue is presumably not the inequality caused by the global adoption of a single theory (capitalism) as that is inevitable but rather with the unfortunate fact that we as Africans are not the ones to benefit.

If this is true, and I believe it must be, then I find your attitude unreasonable and unhelpful. I agree completely with the author in that the continued discourse linking the dominance of Western society over not only ourselves but the entire world and especially all 3rd world coutnries to colonialism, a not exclusively similar case of dominance is inflammatory. It helps the situation not at all and furthers the bi-polarisation of relations between states. The way forward is through hard work by Governments, collaboration between states and sound economic development one way or another, not the reopening of old wounds.

When will Africa be truly free?

Is it possible to break free from the past – a history of the “Scramble for Africa” and power relations of ‘master-slave’, ‘horse and rider’ relationships between Africa and the West, whose legacy has left the continent stripped of its natural resources and cultural treasures? Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman in “Colonial Discourse and Post Colonial Theory: A Reader” give this compelling account and further note, ‘The ending of colonial rule created high hopes for the newly independent [African] countries and for the inauguration of a proper post-colonial era, but such optimism was relatively short lived, as the extent to which the West had not relinquished control became clear. This continuing Western influence, located in flexible combinations of the economic, the political, the military, and the ideological (but with an over-riding economic purpose), was named neo-colonialism by Marxists…” Aimé Césaire also reflects on the psychological effects of the relationship – ‘between the colonizer and the colonized there is room only for forced labor, intimidation, pressure, the police [the military]…he further argues that ‘no human contact, but relations of domination and submission which turn the colonizing man into a classroom monitor, an army sergeant, a prison guard, a slave driver, and an indigenous man into an instrument of production.’

President Thabo Mbeki’s forceful institutional critique against what appears to be an aggressive interference of Western powers in Africa affairs should not be dismissed out of hand. In fact, Mbeki’s statement highlights and reprimands the European and Western intervention in African affairs, and in so doing he captures with precision the historical context and the continuing troubling colonial legacy that Africa has found itself in. Mbeki reminds us that:

(i) ‘Recent events, as in Libya and Côte d’Ivoire, have confirmed that the major Western powers remain interested and determined to attach Africa to themselves as their appendage, at all costs, ready to use all means to achieve this objective;

(ii) to realise this objective, these powers will exploit the universal commitment to democracy, human rights and good governance to intervene in any and all our countries to advance their interests…’

In ‘Decolonizing the Mind’, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o reminds us that this ‘contention started a hundred years ago [perhaps longer than that] when in 1884 the capitalist powers of Europe sat in Berlin and carved an entire continent with multiplicity of peoples, cultures and languages into different colonies’. He further argues that, ‘it seems it is the fate of Africa to have her destiny always decided around conference tables in the metropolises of the western world…’ In contrast, Europe adopted the tenets of non-intervention in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, and the EU has evolved a shared sovereignity – but by agreement of member states.

However, now we have ‘the new Scramble for Africa’ as defined by Matthew Parris, and we see that although the West believes in self-determination, it does not extend this fundamental privilege to Africa. It is not difficult to understand the fact that, Africa continues to suffer heavily, because of the western manipulation and exploitation of its resources. There is no need for me to give examples, because history and the unfolding of recent occurrences have already done so.

Perhaps, it is in this context that both Mbeki and Parris envisage this notion of ‘recolonisation’. When European and Western powers continue to ignore Africa’s rights to self-determination, it seems these ‘powers’ have not forsaken their colonial ambitions, and hence I find Mbeki’s critique to be accurate in this regard.

Threats, military interference, exploitation of natural resources and undermining African institutions and governments by European and Western powers sounds very much like the colonial model to me and thus, the notion the ‘re-colonisation of Africa’ cannot be easily dismissed. What is the rationale for continued interference? Why is Africa always an easy target?

We should all take a collective stand and strongly condemn this pattern of interference. Indeed, it would be shocking for African Commonwealth countries to send operatives to London to confront the current administration because it had failed to protect citizens during the recent riots. Or for English and South African troops to occupy Washington to ensure passage of the health reform act because 45,000 uninsured citizens were dying each year from lack of medical care. The West often finds itself impatient with Africa, but African diplomacy is different. It is based on a deep respect for individual’s human dignity and maintaining community. Leaders will publicly stand together but privately sort out issues quite harshly. It is deeply rooted in the spirit of ‘Ubuntu’, meaning you are who you are, because of the humanity of others. It is this humanity that seems to be lacking in the European and Western world.

This new century calls on humanity to sing a new song of ‘Ubuntu’ and brotherhood, it calls for the people and nations of the world to stand against what appears to be an abuse of power by international institutions, it calls for new imaginings where Africa can no longer be treated as a subordinate of the European and Western powers, but as an equal partner in resolving the problems that affect our globalizing world.

Mbeki’s proposal is that we Africans must ‘develop our own capacity to resolve our conflicts, committed to find African solutions to African problems, in much the same way that, for instance, the Europeans insist, correctly, that they have the right to arrive at European solutions to European problems, as do the people of the United States of America with regard to their problems…’ and in arguing so, he thus captures the essence of Africa’s Renaissance.

There is a greatest human cause, to which we must all respond, the respect for human dignity and freedom of others. President, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela reminds us that ‘For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.’ Let us therefore make a collective pledge to live in a way that will help us recognize the humanity of others. This we can achieve in our lifetime.

I would like to commend you on your very interesting observations and must also convey the fact that it challenged me to think differently.

Wandile Goozen Kasibe is doing his Masters in Museums Studies at Leicester University in Leicester

What the hell did this Mphil student write. Just comonm sense , no theory wil tell you that powwerful nations want to continue powerful and will exert their power to get cheap resources or at best to steal it . The wealth that they enjoy they want to continue enjoy and in a world of inequal equation , some will be masters and others slaves. The only reason China has not fallen in that boat is because they are coming from a past where they had dominated and had critical influence. china also had a history of invention, science and technology. otherwise she would have fallen to the neo colonisation being imposed by england and others.