“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” – Voltaire.

Over Christmas I visited Boston and had the occasion to walk the famous freedom trail: 3 miles of sights commemorating American independence. As I walked this hallowed ground I pondered on those fighting for freedom today, in the streets of Cairo, Homs and Tunis. Having met some of these people, I wondered at the suspicion we direct at the Islamic parties now gaining power, as if we forgot our own history.

American democracy was born of Puritan principles of self-government, but that did not prevent it from evolving into the (more or less) secular body it is today. Ignoring this and condemning Islamic parties not only ignores history; it fosters a dangerous contradiction.

Working in post-revolution Tunisia, I had the opportunity to meet supporters of the liberal parties and partisans of Ennahda, the moderate Islamists. I was shocked to discover that some liberals, egged on by foreign mis-perception, support democratic elections but refuse to acknowledge Ennahda’s legitimacy. Democracy means accepting that your opinion might lose out, hoping that next time around it will win. Encouraging the liberals to perceive Islamic parties as non-legitimate promotes the same sort of paternal authoritarianism that has ruled the Middle East for so long.

History Teaches Us

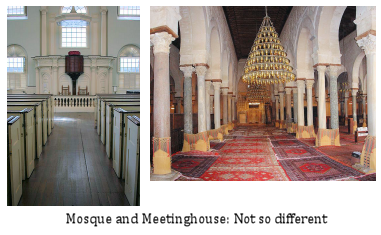

Religious principles have repeatedly proven compatible with democratic politics. In New England the Puritans would hold their religious gatherings in the town meetinghouse. These houses were also used to conduct the town business, intrinsically linking secular and religious affairs through a self-governing church. Not all members of the parish had to go to church, but in order to partake in the town affairs men had to pledge a covenant to the community and under god; an early concept of citizenship. The most famous example is Faneuil Hall in Boston, referred to as the ‘cradle of liberty’ for its role in the American Revolution.

Note that the American Revolution owes as much (if not more) to secular minded men of the enlightenment like Jefferson. But that’s the point: the struggle between a conservative, religion-oriented wing and progressive, secular one has defined American politics to this day.

Let’s look at a more recent example: Turkey. In 1923 Ataturk founded a republic on secular principles. He banned the veil, emancipated women and replaced the Arabic alphabet with the latin one, distancing himself from Islamic traditions. He did this because he believed it would foster progress, but he did it against the people’s will. In fact, he tasked the army with enforcing secularism by force if necessary, and enshrined that role in the constitution.

Today, the Islamic ‘Justice and Development’ party is in power. Having won three free and fair elections, it has full democratic legitimacy. Yet the army continues to challenge its authority, especially around iconic issues like the veil. Some members have even threatened a coup; a fundamentally undemocratic notion.

Risks & Rewards

The Arab spring reveals both the opportunities and pitfalls that hinge on our treatment of Islamic parties. In Tunisia, Ennahda won a solid plurality of votes in a free election, while the liberals secured about 25%. They’ve pledged to respect minorities and refrain from moralistic legislation like the banning of alcohol, focusing instead on economic issues. They’ve publicly distanced themselves from the ultra-conservative Salafists and from statements made by Hamas. Though some remain skeptical, investment and aid has flown in.

In Egypt the situation is far messier. There another democratically elected Islamic government, the Muslim Brotherhood, faces of a more secular but decidedly undemocratic ‘supreme council of the armed forces’. Because of the West’s mixed messages, both side believe they have the international community on their side: the army because they stand against terrorism and for peace with Israel, and the Muslim Brotherhood because they constitute a legitimately elected body. Though many may disagree with the Brotherhood’s principles, they have pledged to respect the democratic system and reached out to parties on the left rather than form a government with the ultra-right Al-Nour party. The more the West waffles on about its principles, the more likely liberals will reject such collaboration and force the Muslim Brotherhood to the right.

Finally, let’s look at Syria. There, an autocrat condemned by the entire international community stubbornly clings to power, accusing his opponents of terrorism. Like Qadaffi before him, he believes the West’s Islamophobia is stronger than its commitment to democracy. So by depicting protesters as affiliates of Al-Qaeda, he hopes to stay on as the lesser of two evils. And why not? For decades, the US in particular has funded military autocrats in the name of ‘stability’ and, more recently, the War on Terror.

Accept and Encourage

We must end this doublespeak. We must stop suggesting that Islamic democracy is an oxymoron! As long as all parties pledge themselves to the democratic process, are willing to concede power when voted out, and respect minorities, they should enjoy the full support of Western powers. We are all the more likely to secure these checks if we don’t condemn Islamic politics out of hand.

I am secular and liberal, but I do not mind (too much) when parties tie their political convictions to the tenants of their faith. I respect their opinions and their right to propose them, just as they must respect mine and my right to vote against them.

If we truly believe in the moderating effect of democracy, we must allow it to run its course: electing parties which the people prefer and then holding them accountable to their promises. We should not ‘pick’ winners based on our preferences, but rather ensure a proper framework for the exchange of ideas.

No discourse, no democracy can exist without disagreement.

Erwin Knippenberg is MSC in Economics for Development in the Department of International Development (QEH).

2 Comments

A very interesting article. But I think people will always pick by their preferences. Everyone always has done and I think to ask people to pick through an objective look at how well someone has performed is too much. We will always judge another on how they have effected ‘me’, not the wider society.

Erwin writes about the rule of Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey, saying “Yet the army continues to challenge its authority, especially around iconic issues like the veil. Some members have even threatened a coup; a fundamentally undemocratic notion.” This statement may be factually incorrect. The key challenge facing Turkey under the AKP rule is not the threat of another military coup, or that the army threatens the country’s civilian supremacy. For dozens of Generals and senior army officers are in prison. The real issue is that, in the guise of democracy, the AKP leaders, Prime Minister Erdogan in particular, has attempted to silence all opposition. There are dozens of journalists and writers who are currently in prison for criticising him or the AKP rule.

Also, what would the author say about the role of Islamist parties in the politics of Pakistan, an idealogical republic created in the name of Islam? Boundaries between what they profess ideologically and what Taliban and other radical groups do in actualising their violent ambitions are really blurred.