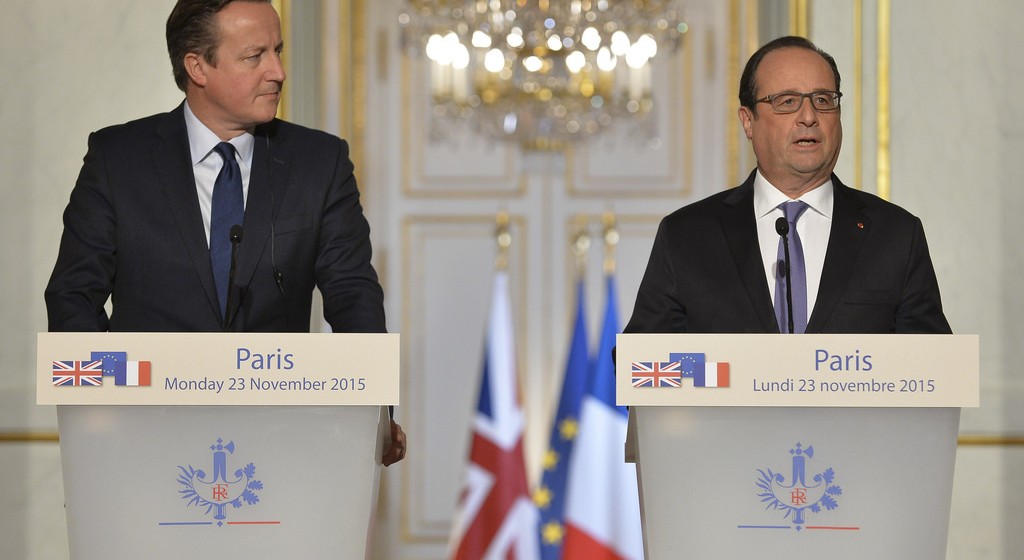

The attacks in Paris have elevated both the desire and the case for a full-scale war against Islamic State in Syria. French President Francois Hollande has vowed not just to fight IS, but to destroy it. The US and Russia are poised to significantly up their stakes, and Prime Minister David Cameron has begun laying out the argument to extend British airstrikes into Syria as well. The war is already underway and likely to escalate into an even greater coalition of military power than already exists.

However, wars are unpredictable. This is especially so in the case of Syria, with multiple non-state armed groups interacting with each other, multiple foreign state actors, and no legitimate government. Even the vast asymmetry in power between the international coalition and IS does not make the outcome predictable: powerful states have often lost wars against much weaker foes, from the United States in Vietnam, to Russia in Afghanistan, to the British Empire in the American colonies. If they have the right strategy and motivation, the weak can win, and this is a trend that has increased over time.

There is, however, one thing that is predictable about war: overconfidence. Even if the outcome of war cannot be known in advance, the historical record shows a remarkable empirical regularity in that politicians, military leaders, and the public on both sides tend to believe they will win, with astounding repetitiveness. Nations around the world and over the centuries have repeatedly underestimated their enemies, overestimated their own capabilities, and exaggerated their ability to control what are inherently unpredictable events. Notably, the bias becomes stronger once we decide we must fight (which is now), and enter an implemental rather than a deliberative mindset.

Overconfidence might seem like a naïve pitfall that has afflicted distant generations or other states—not us. Yet western states have been as susceptible to overconfidence as everyone else, in numerous wars from WWI and Vietnam, to Kosovo and Iraq, and it continues to plague foreign policy. In 2011, French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe acknowledged that NATO had underestimated resistance from Gaddafi’s forces (and hence the war became longer and costlier than anticipated). In 2014, the US Director of National Intelligence himself, James Clapper, admitted they had underestimated IS and overestimated the Iraqi Army.

This overconfident bias might seem surprising, but it should not be. Psychologists and neuroscientists have long shown that human beings have a natural tendency towards overconfidence, or “positive illusions”, a phenomenon that affects most of us most of the time. Indeed, it is considered a vital component of mental health. Optimism engenders resolve and persistence against the many obstacles we face in life. The conclusion of this research is that optimism is actually not just a quirk of western cultures, but a critical ingredient of human nature. While it may help us in everyday life at home, it can become a major disaster for critical judgments about war and strategy on the international stage.

We have already underestimated Islamic State and it is likely that we will continue to do so. At least, that is the conclusion from cognitive psychology and the historical record. Obama and others have impressed us with the number of countries involved in the anti-IS coalition. This is heartening. But it also highlights the problem: with so many powerful countries already in the fight, why are we losing? Evidently, we face an incredibly resilient enemy and ideology on the ground, and one that we are only prepared to engage from the air.

This is not an argument against intervention. It is a prediction that intervention will take longer and cost more than we think. With many coalition states hard pressed to sell another war in the Middle East to a skeptical public, leaders are likely not only to perceive but also to push a vision of rapid victory at affordable cost.

In fact, it will be costly, slow, and any kind of clear-cut victory is unlikely. The ideology will live on even if the current cohort is dead, and with each brother killed, we plant the seeds of new avengers. However tempting it is to claim a comprehensive strategy and the prospect of victory to gain public and political support, great expectations will only lead to greater disappointment. In 1940 Churchill sold the British people a war on blood, sweat, toil, and tears. We should not be promising anything else.

This article originally appeared at Political Violence @ a Glance.