The Italian Left: Reform and win, or perish

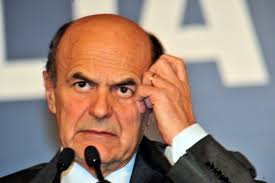

The general election has put the Italian Left in a state of shock. In December, the coalition led by Pierluigi Bersani had a fifteen points lead in the polls, while more than three million people turned up to vote in the leadership primary election. But last week’s election made that seem a long time ago. The final vote produced a new political reality: a hung parliament and the bitterest defeat for the Left in 20 years.

The vote spelled frustration at a whole generation of politicians. The parties which stood for parliament in 2008 collectively lost roughly 13 million votes. The centre-right parties lost more than half of their votes (about nine millions), even though Berlusconi managed a spectacular comeback by leading an unapologetic campaign. It proves that he can still dominate the debate. Mario Monti’s centrist coalition intercepted a further 2.5 million votes, mainly from the centre-right. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, lost 3.5 million votes compared to the last election, which also resulted in defeat. After months of successes in local elections and in the polls, the party portrayed itself as the only responsible force in a country in disarray. But just like Neil Kinnock in 1992, Bersani took the victory for granted. He ran a political campaign where the main objective seemed to reassure the party militants that a victory was finally at hand.

The Liberal Revolution of the Italian Left

The Italian left, heirs to the strongest communist party in Western Europe and a powerful Catholic political tradition, is struggling to adjust its values and political agenda to the new needs and constrains of the modern globalised world. As the Democratic Party seems set to win Italy’s general elections next year, and thus take control of the third largest economy of the Eurozone, such ideological adjustment is now particularly urgent.

Neither Left nor Right: The rise of populist movements in Italy

When an economic crisis combines high youth unemployment and an impoverished middle class, there is a real risk of a rise in right-wing extremism. But the left/right divide does not always help to understand European populism.

The Italian case is a particularly interesting one. After Berlusconi resigned in disgrace, the main two parties (Berlusconi’s People of Freedom-PDL and the centre-left Democratic Party-PD) were left with no choice but to support a ‘truce government’ of non-politicians and technocrats, led by Mario Monti. This unlikely arrangement froze the parliamentary majority.

The Crisis of the Italian Second Republic: In a right mess, but are the alternatives any better?

History, as Marx taught us, likes to repeat itself: the first time in the form of a tragedy; the second, a farce. What may be unique about Italy, though, is it’s often hard to distinguish between the two. This is a country where the situation is often tragic but never serious.