Italy’s post-war political system is not new to dramatic government changes and sudden reversals of fortunes. The experience of the first populist experiment in government thus far is no exception.

The elections of March 4th, 2018, were nothing short of a political earthquake. The most dramatic result was the success of the Five Star Movement (M5S). The political formation, created by comedian-turned-guru Beppe Grillo and led by his former lieutenant Luigi Di Maio, became the strongest party in Parliament with 32.7% of votes, wooing voters away from Matteo Renzi’s PD. On the right, the League took over Berlusconi’s Forza Italia as the main political party, winning over 17% of votes. This ‘sorpasso’ emboldened Salvini to break with the electoral pact with the centre-right coalition, forming an alliance with the M5S in an all-populist government led by lawyer Giuseppe Conte in June. With this new government of M5S and League Italy entered politically uncharted waters.

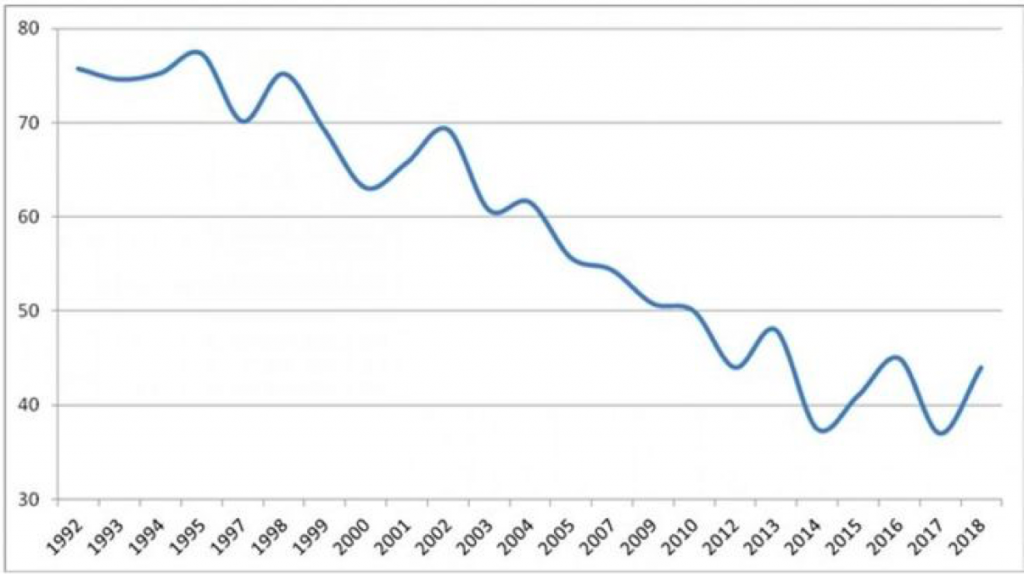

The 2018 elections represented not only a realignment of Italian party politics but the culmination of Italy’s trajectory towards Euroscepticism, which had been marked by a fall in approval for the European project by thirty-nine points in fifteen years, from 76% in 1992 to 37% in 2017, turning Italy into the third most Eurosceptic nation as of 2019, just above Hungary and the Czech Republic.

Before the elections, the M5S promised to take on Brussels and wide-ranging reforms, such an overhaul of tax policy, universal basic income, and increasing public spending above 3% of GDP. But over a year in government, the M5S and its leader Di Maio have struggled to deliver on its campaign promises.. Despite approving the universal basic income and a new pension law, the M5S has reneged on many of its promises, allowing a high-speed railway project connecting Italy and France which it had promised to erase, and accepting a limit on public spending to 2.04% of GDP. As result, the public image of Di Maio’s party after one year and two months of government is that of an inept and weak formation. On the other hand, Matteo Salvini is more popular than ever. Salvini has changed the League’s platform “The North First” to “Italy First” (notably, dropping ‘North’ from the party’s official name, Lega Nord). The key pillars of “Italy First” are security, border protection, and stop to uncontrolled immigration.

Since assuming the post of Minister of Interior, Salvini has implemented a ‘closed port’ policy, denying access to dinghies and ships who had rescued migrants traveling from the African coast. Salvini has been able to present himself as the ‘Captain’ who protects Italy’s border from those who try to enter illegally, be they smugglers conducting dinghies or NGO workers like Carola Rackete, who docked the ship ‘Sea Watch’ transporting rescued migrants in the Lampedusa harbor on humanitarian grounds. Salvini has proposed new legislation on security matters, notably expanding the grounds under which self-defense is allowed, which promotes his image as the true defender of the people vis-à-vis crime and illegality. This has led the League to appeal not just to its traditional base in the North, but also to voters in the Centre-South, who have felt insecure, threatened and abandoned by the political elites in Rome and Brussels for too long. Despite being “the oldest political party in Today’s Italy” (its foundation pre-dates Forza Italia), the League appears to be “the true novelty in Italian politics,” taking away the M5S’s thunder as the anti-establishment political force.

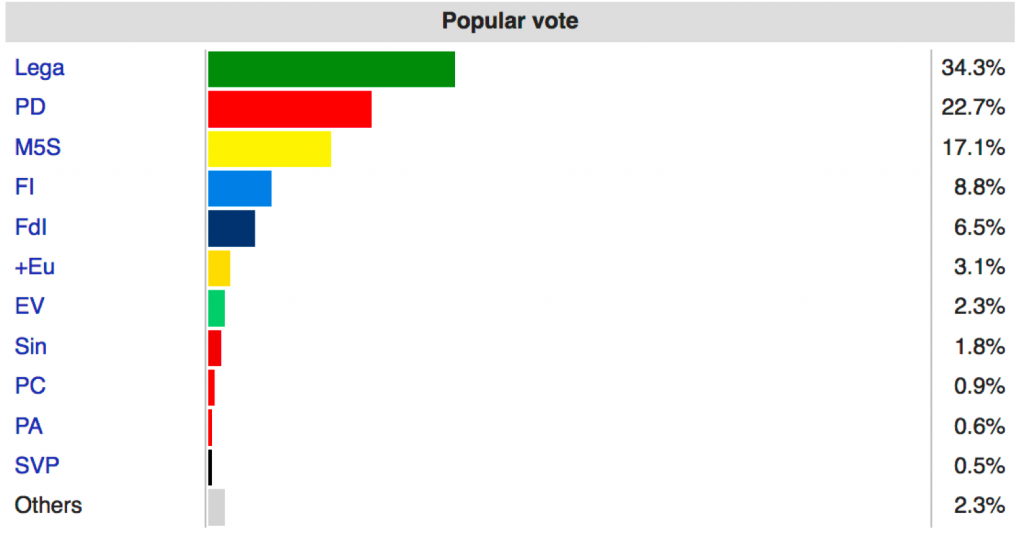

The European elections of May 2019 are a testimony to Salvini’s rise and the M5S’s decline. The League won over 34% of the vote, doubling on the previous year’s success. Di Maio’s party only obtained 17.1% of the vote, coming in third behind the PD (22.7%). Forza Italia lost further votes to the League, falling below the 10% threshold. While the League won most of its votes, in the North, as expected, Salvini’s popularity surged in the South: for instance, he was the most voted politician in Sicily’s main city, Palermo.

Salvini’s popularity seems not to have suffered much from three scandals that have involved the League: 1) its failure to reimburse €49 millions to the state’s finances: 2) corruption charges against Salvini’s economic advisor, Armando Siri; and 3) the opening of an investigation for a potential illicit flow of funds from Russian sources to finance the League’s electoral campaign. Whether these scandals directly implicate Salvini is yet to be seen. However, it is already becoming apparent that they have barely affected the League’s popularity. To a large degree, this is the result of Salvini’s excellent campaign on both social media and on the institutional stage, where he presents himself as the champion of all Italians in the face of the threats that immigration and European bureaucrats pose to identity, economy, and security.

Salvini’s triumph and growing popularity have generated an imbalance in the Italian government. The M5S, despite being the main party in government, appears weaker than ever. In contrast, the League, while the smaller party in government, plays an outsized role: Salvini can now impose his will on key policy areas, knowing that in case of a new election, the League would likely to win by a landslide. Thus, Salvini – the Captain – seems firmly at the helm.