The risk of trivialising international law

The appointment by the United Nations Human Rights Council of a special commission to investigate Israeli actions during the latest war in the Gaza Strip seems to confirm the skepticism with which that organization is held by many people in North America and Europe.

The UN Human Rights Council replaced in 2006 the UN Human Rights Commission. Unfortunately, the change in name was not followed by a change in attitude.

The obsessive concentration on Israel, at the expense of many other countries where human rights are flagrantly violated, is not the exclusive purview of the UN Human Rights Commission, to be sure. The UN in general tends to devote more time to Israel than to any other country; so much so that one wonders if Israel did not exist what would the UN do with so much spare time left.

Can the EU Afford to Lose the UK?

In her book Statecraft, published in 2002, Lady Thatcher wrote, “The blunt truth is that the rest of the European Union needs us more than we need them.” We may soon learn how true Maggie’s words are. In the United Kingdom, some of the most prominent businessmen, journalists, and academics are trying to convince Britons that a British exit, or “Brexit,” would be a disaster for their country. In the rest of the EU, a Brexit does not seem to be a sensitive issue; in fact, many continental pundits seemed happy to see Britain leaving the last European Council with a bloody nose after the fight about Jean-Claude Juncker. Will the EU be better off without Great Britain? Or will a Brexit herald the fall of the EU?

Travelling to the UK? On the Pain, Separation and Dehumanisation of Student Families from ‘High-Risk’ Countries

The violence and despair of the militarised and exclusionary immigration policies of ‘Fortress Europe’ have been well documented. Institutionalised racism combines with an openly hostile bureaucracy of ‘paper walls’. In the UK Home Office, officials are encouraged through a perk system that awards shopping vouchers to officials who decline the highest number of asylum applicants per month. In Fortress Europe: Dispatches from a Gated Continent, Matthew Carr (2012: 120) describes the immigration-media nexus in the UK as a ‘mutually reinforcing consensus between governments, the media and the public that invariably depicts immigration as an endless crisis [and undocumented migrants as] dangerous and dehumanised invaders massing outside the nation’s borders’

New issue of St Anthony’s International Review

St Antony’s International Review (STAIR) is proud to announce the publication of its 19th issue, “Thinking Beyond the State: Emerging Perspectives on Global Justice”. The launch event will take place on 17th June 2014 at 5 p.m. in the Department for Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford. More information on the event can be found here.

In this issue, we ask, how should processes of neoliberal globalisation make us think about global justice beyond the state? There are broadly two possible approaches to this question. First, we might turn from the state to supra-national state institutions. Second, we might think beyond state institutions as such. The academic global justice debate has tended to focus on the first approach. With this issue we intend to broaden the debate by taking seriously the potential of non-statist political and social movements to address global injustices.

Understanding Neoliberal Legality: Perspectives on the use of law by, for and against the neoliberal project

Neoliberal institutional and economic reforms have attracted substantial scholarly attention in recent decades, but the role of law in the neoliberal story has been relatively neglected. ‘Understanding neoliberal legality’ was the subject of a day-long conference I organised at Oxford in June, which was generously sponsored by the Department of Politics and International Relations. The event drew together 40 established and emerging academics from across the UK and as far away as Canada, Finland, and Australia. These scholars have been independently researching various aspects of the role of law in the construction and contestation of neoliberalism. Many are members of major research networks in political and legal studies, such as the Institute for Global Law and Policy based at Harvard Law School, and edit prominent sites of scholarly discussion such as the debuting London Review of International Law.

The questions and dilemmas animating the meeting included the following:

• What form does law take under neoliberalism and to what extent is this new and different?

• What role do the content and form of law play in shaping the economic, political, and ideological pillars of the neoliberal project?

• What are the implications of these shifts for the ways in which neoliberalism is negotiated and resisted?

Policy making in EU Security and Defense: A Q&A with Hylke Dijkstra

Hylke Dijkstra, a Marie Curie fellow here in Oxford, has brought out a book that is of considerable contemporary interest as the EU struggles to relocate itself more firmly in the world not only of economics and finance, but of international relations. Congratulations to him!

Security has been a catch-phrase for our times. Military, civilian, human, legal, economic, environmental? Delivered by states, institutions, by NGOs, by citizens, by armies or judges? The term has been defined almost to ‘meaningless-ness’. Classical defence debates have virtually disappeared from our vocabularies. And no roomful of political scientists could ever agree on an exhaustive list of what the most important security and defence threats actually are. So Dijkstra’s book is an ambitious one.

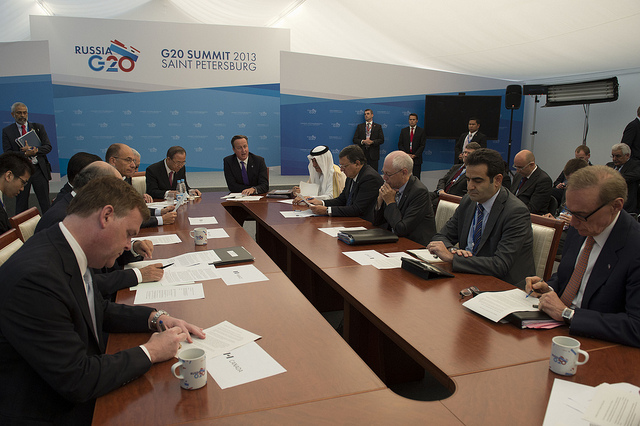

Growth, international trade and energy at the Russian G20

The war in Syria dominated media and diplomatic attention at the G20 in early September in St. Petersburg. At the actual summit, however, the agenda covered mainly macroeconomic and financial issues. Inaugurated in 1999 as a meeting of finance ministers from developed countries and emerging economies, the G20 has turned into a top-level summit coordinating the global response to the financial crisis after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. The G20 summits in Washington (2008), London and Pittsburgh (2009) re-financed the IMF ($500 billion), and established the Financial Stability Board to stabilise the banking system and derivatives markets. More difficult and less successful were the concerted efforts, from 2010 onwards, to couple fiscal austerity with structural adjustments between trade surplus countries (exporters such as China and Germany) and trade deficit countries (importers such as the US and Italy).

Islam and women in Bangladesh’s constitution

I’ve published a new policy brief with the Foundation for Law, Justice and Society, exploring the vexed issue of women’s rights on the Indian subcontinent, through the prism of the shifting emphasis of secularism and Islam in the Bangladeshi Constitution, and the impact this has on gender equality and family law.

As the world reacts to the conviction of the four men whose gang rape of a young woman in a moving bus in Delhi sparked riots and international condemnation, the policy brief, entitled Islam and Women in the Constitution of Bangladesh, provides a timely insight into the complex interrelation of law, religion and gender politics on the subcontinent.

My report finds that whilst the Constitution has been referred to in only a limited fashion in cases involving the protection and enhancement of women’s rights, notable exceptions include violence against women resulting from religious edicts: “In response to a spate of violence directed at young rural women as part of their sentencing by fatwa … the Supreme Court declared such sentences unconstitutional in 2001.”