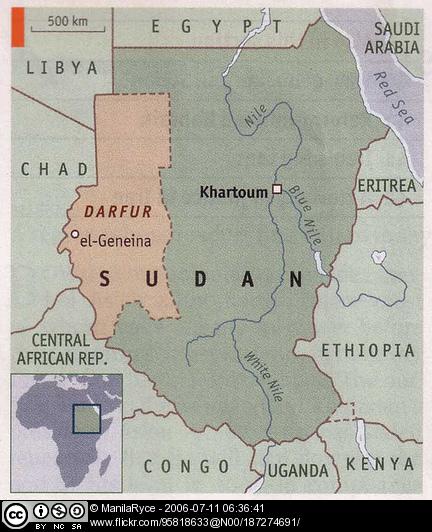

Following decades of internal civil strife, on July 11, 2011, the African nation of Sudan separated into two de jure sovereign states as the South finally gained its long-awaited independence. Yet those with any sort of intimate knowledge of Sudan will have viewed the scenes of jubilation across the South and the calm acceptance displayed by the North on the day of separation with caution. Although South Sudan’s moral claims to independence were never in doubt, its possibility of a peaceful future appeared, if anything, less certain following its separation from the North. A year on, it is a prescient time to reflect on how Africa’s most recently divorced couple are faring on their separate paths.

For South Sudan, like any mistreated spouse, freedom was seen as an end in itself, the only path to dignity and happiness. Such an attitude was understandable given the brutal repression the people of South Sudan suffered at the hands of their northern compatriots for so long. However, so focussed were they on obtaining a separation that vital questions regarding how life would be afterwards were left unanswered. As a result, although the South maintains its joy at gaining independence, it is only now beginning to realise the enormity of the task of living alone.

Regrettably, South Sudan celebrated the anniversary of its independence amid an economic and political crisis. The decision to halt oil production, following a spat with the North, has meant that the previously faltering economy has now all but ground to a halt. Salva Kiir has now confessed that the country doesn’t even have enough money to support its current cabinet, resulting in the proposed closure of several ministries.

Economic malaise, however, is but one of a series of interlinked and serious problems facing the world’s newest nation. For one thing, corruption is rife, with Salva Kiir accusing officials of stealing over $4 billion from government coffers since 2005, a galling sum for a state whose GDP per capita languishes at a pitiful $150 per annum. In addition, with less energy now focussed on the common enemy of the North, space has opened up in which previously dormant fracture lines between the disparate ethnic groups have been able to reassert themselves. Although South Sudan has fervently sought to deny all incidents of inter-ethnic violence in a desperate effort to maintain the myth of a coherent and unified South Sudanese identity, reports of such confrontations have continued to rise.

Given its infancy and the complexity of the problems it faces, the Government’s failure to sufficiently address these issues is understandable – perhaps even excusable. What many observers cannot pardon or justify, however, is the failure of that same government to, at the very least, guarantee its population the protection of their human and civil rights.

Ironically, one of the driving reasons cited by South Sudan in its bid for independence from the North was that it sought to secure the rights of its people. Yet it would now appear that the new government of the South is just as unwilling to grant them those liberties that have so long been withheld from them. Of particular concern are the repressive activities of the security services and the curtailment of media and press freedom. Serving as just one example of many reported incidents, on the eve of South Sudan’s first anniversary of its independence a leading civil society activist, Deng Athuai, was found beaten into a coma and left by the side of the road. It is events such as these which cause many to worry that South Sudan will become “just another sad African story”. Other indicators of concern include the beatification of the army, with the face of John Garang, the martyred leader of the SPLA, adorning every note of the new currency.

That good governance has proven difficult is not surprising. On the eve of its independence South Sudan was a nation with only 100 miles of paved road and in which a woman had a greater chance of dying in childbirth than of achieving literacy (According to UNICEF 1/9 women die in childbirth while only 1/100 complete primary school). Moreover, it is a well-known fact that armies do not often make the best leaders of avowedly democratic nations – the command structures and modus operandi of rebel armies simply do not adapt well to the demands of democratic politics: The inherent necessity of an army to maintain unity and solidarity makes soldiers-turned-politicians unduly wary of criticism and dissent.

The greatest concern is that, faced with so many diverse problems, the new leaders of South Sudan will revert to the only thing they really know well; fighting. Already their inability to provide the citizens of their country with the governance needed to develop has led them to focus the political debate on the on-going conflict with the North.

For its part, the divorce has left the North poor and bitter, having lost a good chunk of the marital assets in the separation, namely the oil fields just south of the border and more than a third of its revenue. The economic shock resulting from these losses has necessitated a painful curtailing of food and petrol subsidies leading to rapidly escalating consumer prices. Unsurprisingly, the last month has seen some of the biggest protests of recent decades both in Khartoum and across the rest of the country.

The level of protests and their cause should frighten Bashir’s government since it was the spiralling prices of sugar in the sweet tea addicted nation which felled the Nimeiry regime in 1985. Even more concerning for the government, however, the crowds in Khartoum also have wider demands like freedom and democracy, as well as deep-seated grievances such as the besmirching of the name of their country by their ICJ-indicted president.

Although Bashir has dismissed the protestors as “bubbles that will be blown away”, the level of unrest is such that many Sudanese are beginning to hope for their own Arab Spring. To those who dare to dream of such things, Bashir has issued a chilling warning: “those who expect an Arab Spring will not see it because Sudan has a hot summer that will burn its enemies and grill them.”

Once again, it far from unreasonable to suppose that the North plan to distract their critics by focussing on the conflict. Worryingly for the South, the North still possess far greater firepower and may therefore be all too willing to allow their current squabbles to slide into full-scale war. Bashir’s vow to reunite the two Sudans indicates he may already be considering this policy.

From a brief analysis of the two nations a year after their separation, it appears that neither country has been better off without the other. Rather, the suffering incurred by the divorce has been so great that those in power are running out of options to maintain their positions, while brinkmanship and desperation threaten to see the bickering between the two former partners to spiral out of control. Time may be running out for peace.

Kate Brooks is an Oxford MPhil student in International Relations

No Comment