Iain McLean and Jim Gallagher on Scottish independence

Prof Jim Gallagher and Prof Iain McLean, co-authors of Scotland’s Choices, answer questions about the Scottish independence referendum. They give their views on many of the issues at stake, including citizenship, currency, higher education, and the European Union. Asked to consider a ‘yes’ victory, they explain the complexities of independence negotiations between the Scottish and UK governments.

Travelling to the UK? On the Pain, Separation and Dehumanisation of Student Families from ‘High-Risk’ Countries

The violence and despair of the militarised and exclusionary immigration policies of ‘Fortress Europe’ have been well documented. Institutionalised racism combines with an openly hostile bureaucracy of ‘paper walls’. In the UK Home Office, officials are encouraged through a perk system that awards shopping vouchers to officials who decline the highest number of asylum applicants per month. In Fortress Europe: Dispatches from a Gated Continent, Matthew Carr (2012: 120) describes the immigration-media nexus in the UK as a ‘mutually reinforcing consensus between governments, the media and the public that invariably depicts immigration as an endless crisis [and undocumented migrants as] dangerous and dehumanised invaders massing outside the nation’s borders’

Towards a progressive capitalism

Labour’s challenge is to position the active state and responsible ownership as essential prerequisites of business success in an age of intensive global competition

Among the most insistent questions in British politics is what model of capitalism the UK needs to remain a wealthy and cohesive society. Since the financial crisis, public disquiet about avaricious global capitalism has been palpable. The growing unpopularity of business and large corporations risks undermining the moral compact in favour of open markets. The backlash against the private sector is hardly surprising: when financial institutions broke down following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2007, the costs fell not on wealthy financiers but society as a whole in an era when middle income households were suffering an unprecedented squeeze.

The irony is that both bankers and the left have faltered in the wake of the crash. Far from gaining politically from the ‘crisis of capitalism’, the Labour party has been left utterly disorientated. The New Labour model of political economy was shaken to its core, having pledged allegiance both to Thatcherite deregulated markets and an overly complacent social democratic model of ‘tax and spend’. Despite delivering forty four consecutive quarters of nominal GDP growth, Labour’s embrace of 1980s neo-liberalism guaranteed neither economic stability nor the sound productive base necessary to sustain long-term social investment.

The Blair/Brown economic legacy was one of under-investment in key infrastructure, notably transport and energy; a continuing decline in manufacturing contributing to a structural balance of payments deficit; an accelerating regional economic divide; and a speculative property and construction boom financing public and private consumption through highly leveraged government and household debt. Not everything about the pre-2008 model was proved wrong: far from it. Research, innovation and high-tech start-ups flourished; labour market flexibility generally kept unemployment down; Britain’s cities underwent a renaissance; the United Kingdom remained a successful base for global companies. In the meantime, financial services – including the City of London – have bounced back from the crisis as the leading-edge professional services centre in the EU.

Nasty piece of work: The Sun’s nationalism is doing England great harm

Other than war, few things fire nationalist sentiments in a society quite like sport. On June 27 2010, as the English football team were being thrashed by Germany in the World Cup in South Africa, England’s fans chanted: “Two world wars and one world cup … two world wars and one world cup!”

As pacified contests, sports generate all the emotions of national attachment in a manner that is generally benign and fun. Yet major sporting events also offer opportunities for those seeking to mobilise national identity in a more aggressive way – as The Sun newspaper recently reminded us with its free “Historic Edition”, dispatched to 22m homes in Britain last month.

Make no mistakes about the official prompt of this paper being the start of the World Cup – this is quite visibly a deliberate political publication, the latest effort by the UK’s highest circulation newspaper to shove popular understandings of national identity in its preferred direction. The effort is hardly covert, with the front cover emblazoned with the words “THIS IS OUR ENGLAND” superimposed over the faces of 117 individuals the Sun deems personal embodiments of “the essence of England today”.

The paper’s contents offered an unusually sustained illustration of English nationalism as interpreted by Britain’s tabloids. It’s not a pretty picture. After a superficially worthy iteration of that now trite sentiment of British politicians, public intellectuals and commentators that national pride needs to be “reclaimed” from the “small-minded” and the “racist”, the following 21 pages provided a tour de force in national chest-thumping that could barely do more to put its small-mindedness and contempt for the rest of the world front and centre.

Democratic wealth: Could republican ideas provide the framework for a new economy?

Call yourself a ‘Republican’ today and people will either think you are a member of the US political party or want to guillotine the Queen. Yet a resurgence of interest in republicanism within academic circles is reclaiming the tradition, while the post-crash political landscape has brought to the fore demands for citizen participation and an interest in sharing control of the economy that can be read as republican in spirit.

An emerging contemporary republicanism within academic circles could provide a framework for building a citizen-led economy. But is there the political will to begin developing this kind of agenda?

In ‘A Discourse on Political Economy’, Jean-Jacques Rousseau gave his take on how a government should tackle inequality: ‘prevent extreme inequalities of fortunes; not by taking wealth from its possessors, but by depriving all men of means to accumulate it; not by building hospitals for the poor, but by securing the citizens from becoming poor’. This is a pretty good definition of today’s buzzword ‘pre-distribution’. Rousseau was a republican who applied these principles to his thinking on the economy, and it is this tradition of economic republicanism that is now being re-examined within academia. Since the first colloquium on the subject was held in Paris in 2007, thinkers across Europe and the US have been furthering the application of republican thinking to the market-driven developed world. Spain, where republican theory was explicitly used as a guide by the Zapatero government in 2004-2011, has provided practical insight in this field, while in the Republic of Ireland, Fintan O’Toole has argued for radical reform to implement genuine republicanism. We might expect American academics such as Michael Sandel, Alex Gourevitch and Thad Williamson, but the renewed interest in academic circles is not limited to republics. In Britain, the work of Phillip Pettit and Quentin Skinner is being read in a new light, towards developing a republicanism that can provide an alternative to market domination.

The Future of the Union: Stick or twist?

I want to consider the constitutional implications for the United Kingdom following September’s referendum on Scottish Independence.

If Scotland votes ‘No’

The constitutional consequences are easier to see in the case of a `No’ vote in September. Scotland is then almost certain to be offered more devolution, since all three major UK parties have promised further devolution of taxation powers. That, however, could further unbalance its position in a United Kingdom based on asymmetrical devolution. It is possible that the English Question would be resurrected, and that the Union would come under threat, not from Scotland but from England. England of course is by far the largest and most populous part of the United Kingdom, but the only part of the United Kingdom without a Parliament or assembly of her own. It is therefore the anomaly in the devolution settlement. But her reliability has perhaps been taken for granted, and English nationalism has not, until recently been a political force of any moment. Part of the reason for this no doubt is that, with a characteristic lack of logic, many in England have failed to recognise the distinction between being English and being British, treating the two as interchangeable. This may now be changing as a result of devolution and of euroscepticism, stronger in England than in other parts of the country. Perhaps UKIP is best understood as an English nationalist party, the English equivalent to the SNP. It favours an English parliament.

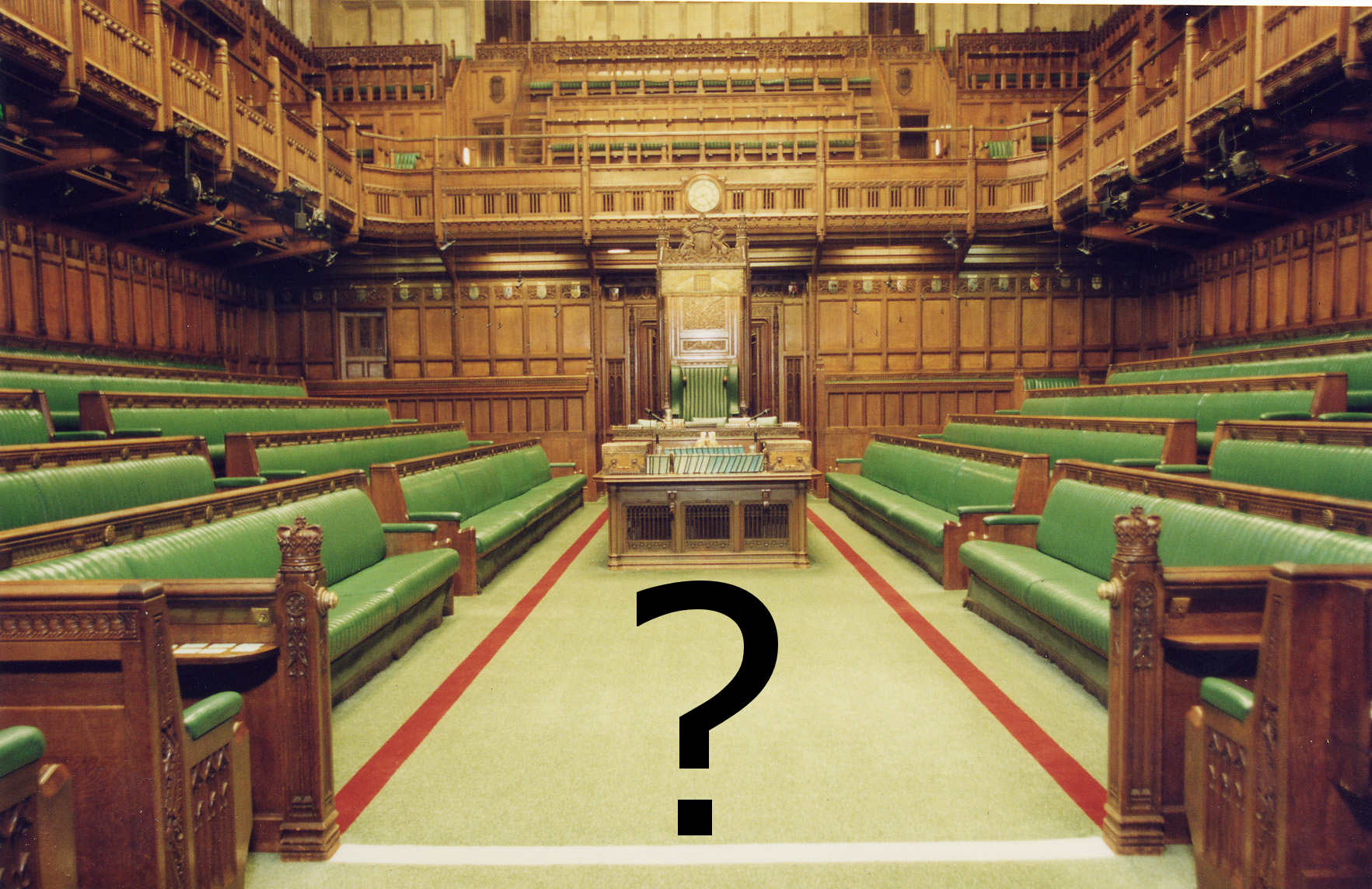

Central Government Makeovers

Have repeated ‘makeovers’ created a government machine in the UK that works better and costs less? Or has a relentless focus on cost-cutting damaged traditional administrative values? In a wide-ranging study of UK central government, we found that not only did formal complaints and legal challenges to central government rise sharply over the three decades up to 2010, but government administration costs also increased by two-fifths in real terms – even though the civil service lost a third of its staff. They conclude that traditional headcount reduction measures do not guarantee a reduction in costs and may lead to more complaints and challenges. We question why government makeovers so rarely start by carefully identifying what citizens actually complain about.

Four locals and a European: What the 2011-14 elections might tell us about the 2015 general election

As the dust settles on the results of the 2014 local and European elections several questions remain unanswered about what the results mean for the future of British politics: Who will win the next general election? How well will UKIP do? Are the Liberal Democrats doomed?

Although local and European elections are notionally concerned with who represents us at the local and European level, most media analysis and political commentary about the electoral results is more concerned with national politics (as indeed are the decisions of many voters). Two years ago I developed a simple statistical model that tries to predict the outcome of general elections from local election results. Although local election and general election results tend to be quite similar to begin with (the two are 90% correlated) a statistical prediction might offer a better indicator of what is likely to happen in the future then simply taking the results at face value. Local election results tend to differ from general elections in certain predicable ways – for example incumbent government parties have tended to perform worse on average at local elections than their eventual general election results by about 4.5%. Controlling for these factors improves the predictive power of local elections by about 40%: the vote share for each party at local elections is 4.4 percentage points different on average from their share at the next general election. The average difference between the vote shares fitted by the model and the eventual results is only 2.7.